JAMES HILLMAN

From an interview with James Hillman, a psychologist and cultural critic, on the current American cultural climate:

Pythia Peay [interviewer]: The death of the old always implies that something new is coming.

James Hillman [in an exasperated tone]: This looking for the “new” is an American vice! We always want to see what’s coming next—we’re addicted to the future! Futurism is another American myth: whether Kennedy, Johnson, Reagan, or Obama, American presidents all come into office with a new program and the conviction that the country is going to be better than ever. But I think you have to hasten the decay. The classic view is always to look back, and to watch and help the dying.

Peay: As I hear you speak I’m thinking of how my family and I helped my father die, which was a very profound experience. And I’m wondering what a similar experience might mean in a cultural sense.

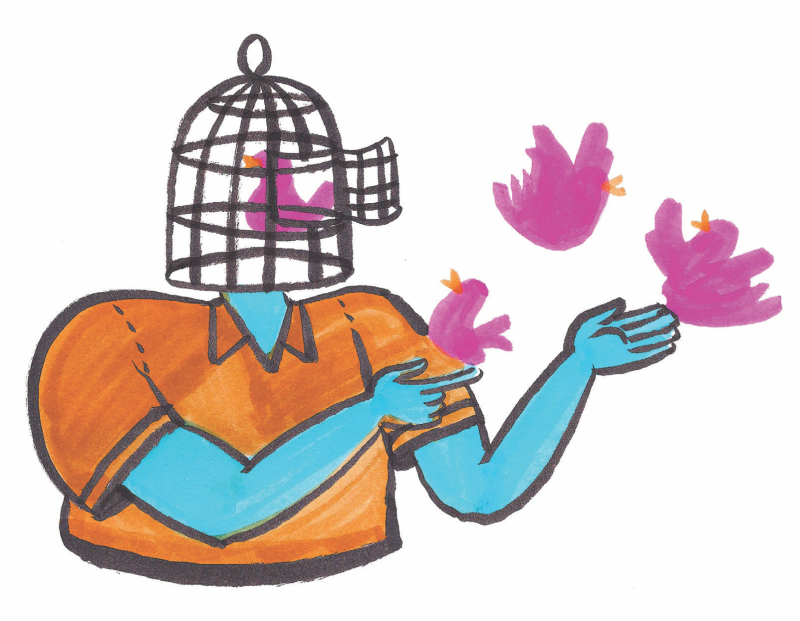

Hillman: One would have to think about what needs to die in this culture; what attachments need to slip away, such as white supremacy, male supremacy, and the sense that we are the really “good people.” America has a certain hubris about its virtue. Another thing would be our “unanalyzed” understanding of the word freedom. Probably one of the striking things in the dying of your father was his dependence on help, like nursing homes and nurses and crutches—yet out of his lack of freedom arose another kind of freedom.

Peay: My father was particularly stubbornly American in that regard. He wouldn’t even go into a hospital, because then he wouldn’t be “free” to smoke or drink. But you seem to be saying that as we lose one kind of freedom, there arises the possibility of another kind of freedom.

Hillman: I’m saying that we haven’t thought about the idea of freedom enough. It needs to be internalized as an inner freedom from “demand” itself: the kind of freedom that comes when you’re free from those compulsions to have and to own and to be someone. For example, think of the kind of freedom that Nelson Mandela must have experienced when he was imprisoned. He completely lost his freedom in the outer world, yet he found freedom within. That’s an example that broadens our current limited idea of freedom: that I can do any goddamn thing I want on my property; that I am my own boss and don’t want government interference; that I don’t want anybody telling me what I can and can’t do; that we’ve had too much regulation, and so on. This is the freedom of a teenage boy.

From America on the Couch: Psychological Perspectives on American Politics and Culture, © 2015 by Pythia Peay. Reprinted with permission of Lantern Books.

DZIGAR KONGTRUL RINPOCHE

In our daily life, we have to learn how to work with our limits intelligently and productively. But when we are safely on our meditation cushions, we should feel free to go all the way. Mentally, we can perform any altruistic acts we like as a way of training our minds. We can imagine offering our body to a hungry tiger, saying, “Eat me up completely, to your full satisfaction.” We can practice lojong [mind training] in this way, even if in real life we might just throw the tiger the banana in our hand and run away (or even run away with the banana). It’s natural for there to be a gap between what we do in real life and what we do on the cushion. But in the safety of our room, we can wholeheartedly drop our care for the small self. When our self-importance comes up, we don’t have to cater to it at all. In our minds, we can follow the instructions of the profoundly humorous yogi Geshe Ben [b. 11th century], who said, “Whenever the selfish, indulgent mind pops up, I give it a whack on its nose, like one does with a troublesome pig.”

From America on the Couch: Psychological Perspectives on American Politics and Culture, © 2015 by Pythia Peay. Reprinted with permission of Lantern Books. From The Intelligent Heart: A Guide to the Compassionate Life, © 2016 by Dzigar Kongtrul. Reprinted with permission of Shambhala Publications, www.shambhala.com. Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche is a Tibetan Buddhist teacher and the founder of Mangala Shri Bhuti, a community with centers around the globe.

THINLEY NORBU RINPOCHE

I have spent the greater part of my life in the East and so have always been involved in Eastern social customs, which are very rigid and restrictive. I have also been involved in the tradition of dharma, which is also in its own way quite rigorous. Some of the people I met in the West were involved in dharma and some were not. I found that a lot of the people not involved in dharma are simple people with very good minds. I also found that some Westerners practicing dharma are actually being harmed by it—their minds are deteriorating. A lot of people I met who are not involved in dharma are very direct and straightforward, without many thoughts, doubts, or worries. Many people involved in dharma, on the other hand, have a lot of doubts and worries and are not exactly straightforward. This made me think that perhaps in some ways it’s better not to practice dharma. Buddha Shakyamuni said that the source of all dharma is directness, and in my experience people who know nothing of dharma often tend to be very direct. Having learned a great deal about dharma, people tend to become involved in the artificiality of mental fiction and so become much less direct. The teachings of dharma have in fact taken them away from dharma.

In the tantras and in Dzogchen it is said that one must leave awareness alone, naked, without doing anything to it, and without creating anything artificial whatsoever. A great many people who have heard a lot about dharma can never do this; they are always creating a lot of artificial conceptions. But people who have heard nothing of dharma do not tend to create artificial conceptions, and I think it would be easy for them to leave their awareness alone and as it is, because they have not created anything to obscure it.

From Echoes: The Boudhanath Teachings [Books in Brief] © 1977, 2016 by the Estate of Kyabje Thinley Norbu Rinpoche. Reprinted with permission of Shambhala Publications, www.shambhala.com. Thinley Norbu Rinpoche (1931–2011) was a prominent Tibetan Buddhist teacher and the author of numerous popular dharma books.

SHINZEN YOUNG

In everyday life, we tend to perceive ourselves as objects, as things. Human languages both reflect and reinforce this perception. But in point of fact, self is not just a thing; viewed deeply, it’s also a doing, a wave. A wave is anything that goes through fluctuations, gets stronger and weaker, has peaks and troughs, spreads and subsides. Our sense of self certainly goes through such fluctuations. When you are alone at night, safe under the covers, your sense of self is somewhat diminished. On the other hand, if you walk into a room full of judgmental strangers, and everybody stops to stare at you, your sense of self grows larger. It wells up as a wave, a billowing of self-

referential mental talk, mental images, and emotional body sensation. Later, as you grow comfortable with the people in the room, the amplitude of that self-wave subsides a bit.

When we look carefully, we discover that the sense of self is not a particle that never changes, but rather a flow, a wave of thought and feeling that can increase and decrease and is therefore not permanent. Because it is a fluctuating wave, not a solid particle, the Buddha described it as anatta. An– means “not,” and atta means “self as thing.” It’s not so much that we don’t have a self, rather it’s that the self we do have is not a thing. It is an impermanent, fluctuating activity; a process, not a particle; a verb, not a noun.

From The Science of Enlightenment: How Meditation Works, 2016 Shinzen Young. Reprinted with permission of Sounds True. www.soundstrue.com. Shinzen Young is an American meditation teacher. Originally ordained in Japan as a monk in the Shingon tradition, he now teaches Vipassana.

BRAD WARNER

If it doesn’t sound like “don’t be a jerk” it’s not Buddhist teaching.

From Don’t Be a Jerk, Reprinted with permission of New World Library, 2016. Brad Warner is an American Soto Zen monk and popular author.

TSULTRIM PALMO

When I found out that I had cancer, the doctors gave me a mere six months to live. Ani Pema [Chödrön] was there, and she designed practices especially for me and my situation, to help me die and use the time I had left as well as possible. I still do those practices today. One of them is aimed at helping me open my heart to others and not cherish my ego. When I feel discomfort, which happens often these days, I think about people who are suffering just as much as I am if not more, and I liberate myself for them. I liberate myself as one of them and not as someone who is separate from them, “little old me.” Then, during the day, I recite the following chant: “When appearances of this world dissolve, may I, with ease and great happiness, let go of all attachment to this world.” “When appearances of this world dissolve” refers to the moment of death, and “may I, with ease and great happiness, let go of all attachment to this world” refers to the training in letting go of all my attachments. I look at what I possess, and if there is something I am particularly fond of, I give it away.

From Choosing Buddhism: The Life Stories of Eight Canadians, edited by Mauro Peressini. Reprinted with permission of University of Ottawa Press and Canadian Museum of History © 2016. Tsultrim Palmo (1933–2010) was a Polish Tibetan Buddhist nun and a former director of Gampo Abbey in Nova Scotia, Canada.

SAYADAW U TEJANIYA

I can look back and see the pattern of gaining and losing momentum in my practice. I would do things to extremes: good things to extreme and then bad things to extreme. I would go on retreat to the monastery and tidy myself up and then come home and slip into old habits. My mindfulness was not continuous; therefore, I was not building good samadhi [concentration]. I could see what was required to take my practice forward, but the balance was still with the defiled mind. My practice was a stop-and-start affair. It’s like taking a high jump: you take the run up to gain momentum, look up and see the height of the bar, and then stop and walk back; the momentum wasn’t enough to take the jump. Momentum is so important in every aspect of our lives: education, social interaction. It’s momentum that improves and makes whatever we do easier; it allows us to grow. If a doctor stops practicing for six months and then comes back to it, he or she will feel unsure and out of touch. Any type of work we do, we need to be close to it, to touch it and be familiar with it. This is what gives us momentum.

From When Awareness Becomes Natural © 2016 by Sayadaw U Tejaniya. Reprinted with permission of Shambhala Publications, www.shambhala.com. Sayadaw U Tejaniya is an internationally known Theravada Buddhist monk who serves as meditation teacher at the Shwe Oo Min Dhamma Sukha Forest Center in Myanmar (Burma).

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.