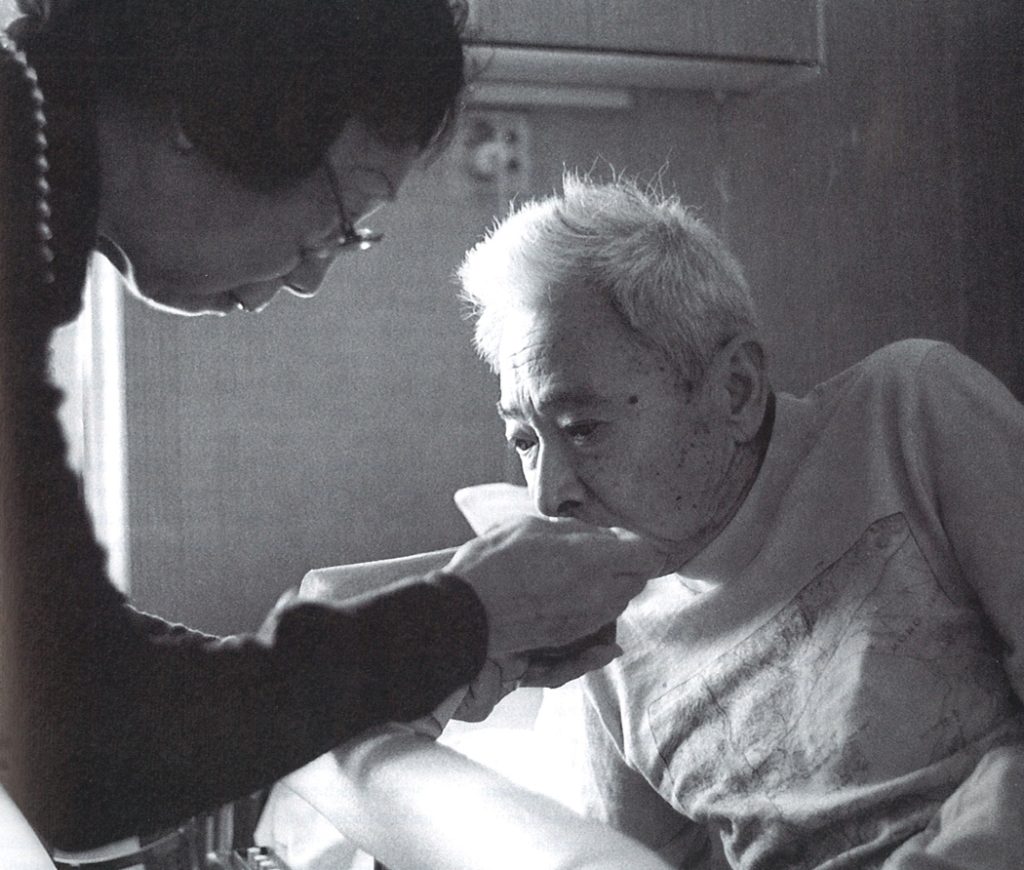

Being present is based on the cultivation of mindfulness in whatever we do. Through mindfulness, we develop greater composure and a heightened sensitivity to nonverbal communication. Then, to the extent that we ourselves are present, we can radiate that same quality outward to the people around us. It is hard to be generous, disciplined, or patient if we are not fully present. If we are present and attentive, and our mind is flexible, we are more receptive to the environment around us. When we are working with the dying, this ability to pick up on the environment is invaluable. The more present we are, the more we can tune in to what is happening. At the same time, that quality of presence is contagious. The dying person picks up on it. The people around him pick up on it. Presence is a powerful force. It settles the environment so that people can begin to relax.

Working with the slogan “Be Present” does not mean that we have to plunk ourselves down and practice formal sitting meditation when we are with dying persons. Although that can be a very powerful thing to do, it is not always possible; and for some people, the formality of that approach could be an obstacle. But we can take the same quality of presence cultivated in sitting practice and extend that out. No matter what we encounter, whether it is possible for us to practice formally or not, we can still put ourselves in touch with that sense of simplicity and attentiveness, the basic presence that formal meditation cultivates—and project that out. We are learning to value nonaction, being as well as doing, and we are communicating that quality to others.

—from Making Friends with Death: A Buddhist Guide to Encountering Mortality © 2000 by Judith L. Lief. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc., Boston.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.