“Larry-san,” says Roshi, “you have cow-shitting posture. Ha! Ha! Look like this.” Rounding his back and dropping his chin toward his chest, he imitates an orangutan or someone with intractable neurological disease. His laughter is so contagious that, even as my anger mounts, I find myself echoing it. “Larry-san cowshitting! Ha! Ha! Ha!”

This is my private interview with him, what we call kan-sho ordokusan, on the third day of a seven-day retreat. A moment ago, when I entered this room, I felt extremely confident, almost cocky. I had been feeling, if not exactly comfortable, a measure of stability on my cushion. Given our past history, the endless collisions I have endured between his point of view and my own, I ought to have known that I was headed for trouble. “Listen,” he continues, suddenly serious. “What you doing on your cushion? Impossible sit like that. Wasting lot of energy! Back bent, thought come. You know that! Head forward, mind become dark, discourage. Must straight! Must bravery on your cushion. Don’t cheat yourself, Larry-san! Don’t waste time!”

Like many Zen students, I learned the rudiments of sitting meditation from the diagrams in the back of The Three Pillars of Zen. I found the Full Lotus impossible, but after four or five months of diligent stretching, I managed what I thought was a pretty fair Half Lotus. I thought I would never add the other half to it, but things changed about a year after I began to sit when I did a month’s solitary retreat at a borrowed cabin in the woods, sitting three, then four, and finally five hours a day. This was my first experience with extensive meditation, and even though five hours isn’t all that much by Zen standards, the inspiration it brought was incendiary. Two days before leaving, I entered a state of mind in which a physical limitation of any sort seemed imaginary. My body was not my master but a docile, infinitely malleable servant of my will. Without thinking, I turned the soles of both feet upward and pulled them high onto my thighs and remained thus, in perfect Full Lotus, for more than an hour. It was an ecstatic experience, releasing a kind of energy I had never known before, but when I tried to get up, I found that my legs were frozen and, from my toes to my thighs, completely numb. I thought of screaming for help, but my cabin was too isolated for anyone to hear. At least fifteen minutes passed before I was able, inch by inch, to slide my feet off my thighs, another fifteen before I was able to stand. Ten years would pass before I’d attempt the Full Lotus again.

I am trying to introduce the matter gently, hiding my embarrassment at something I take to be the bete noire of any Zen student, especially Westerners, the mostly unspoken horror we all confront when we take our seats on the cushion. Why is posture so seldom discussed? For one thing, because it is banal. How humiliating to speak of spine and breath and cushion-height when undertaking the loftiest enterprise of one’s life. The truth is, even though zazen reminds us constantly of posture, exaggerating every nuance of misalignment until an infinitesimal deviation in the spine can feel like a deformity, sitting meditation is possible only to the extent that posture can be forgotten. Where can we find a better metaphor for duality, the tenacity of clinging mind, than in the imperious voices that nag at us as we skirt the edges of samadhi? Stop leaning! Breathe through your low belly! Don’t slouch! Relax your shoulders! And most cruelly: how can you expect to sit if you’re obsessing about your posture?

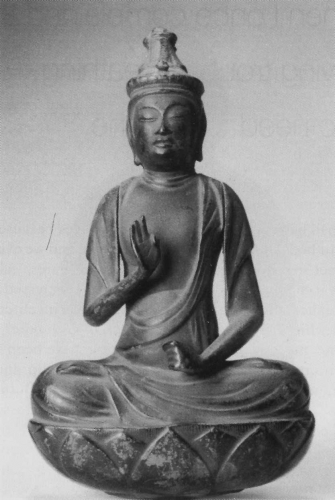

Of course, another reason we hear so little about posture is that everyone thinks that everyone else does it better. Looking around our zendo, I see nothing but buddhas. At the front of the room, Roshi rises from a cushion maybe four millimeters thick, legs flipped so easily into Full Lotus that they might be on hinges. How many times has he told me that he prefers to sit alone because it annoys him to get up more than once every couple of hours? Even when fellow students confess to me that they are not strangers to, say, back pain or bouts of suffocation on their cushions, it is inconceivable to me that their martyrdom approximates my own. Didn’t Roshi tell me once that with the exception of one other student (an obese, elderly fellow with very short legs, who once toppled off his cushion in a faint), I have the worst posture in the zendo? Doesn’t he laugh at me every time I come to dokusan? “Why you looking sideways, Larry-san? Out the window! Jane-san, next to you, she think you looking down her dress!”

It was after my excursion into Full Lotus that I made my entry into institutional Zen. The zendo I visited was and remains the most elegant, the most Japanese, the most orthodox to be found on these shores. In those days, some twenty-five years ago, there was a certain vehemence about the forms of Zen that has mercifully diminished over the years, and at no place was it more evident than here. I felt a bit intimidated as I sat down on my cushion, but my retreat experience had given me confidence—the beginnings, in fact, of a Zen ego that would cost me dearly over the years—and my bout with Full Lotus, disastrous though it had been, had left me feeling, about Half Lotus, the way a marathoner feels about a five-mile run. Such confidence, in combination with the electrified atmosphere of the zen do, produced a great rush of exhilaration. I felt heroic, completely stable on my cushion. Then the monitor, correcting posture while making rounds with the so-called “helping stick” or keysaku, brought me back to earth. Using the stick as a plumb line, he moved me to my left until I was straight by his evaluation and, by mine, listing at something like forty-five degrees. In all probability, it was more like ten, or even five, degrees, but as anyone can tell you who has tried sitting meditation, there is a tendency to exaggerate almost any sort of self-evaluation. For a moment, I felt like the victim of a practical joke. Could this be a sort of teaching, a practice in disorientation meant to humble the rational mind? But how could I deny his plumb line, how question evidence so inarguably objective? And how, if I could not, could I avoid the horrible conclusion that my body image was so at odds with reality that it came close to being a hallucination?

Later, when sitting ended, I sought out the fellow who had corrected me. I wanted to thank him and, since at the moment he happened to be the only authority available to me, seek his advice. Where, I asked, did one go for this sort of problem? Were there exercises? Classes at the zendo? Books to read? “Beats me,” he said. “All I can tell you, pal, you better straighten yourself out. Otherwise you can forget about zazen. How’d you get that way anyhow? Car wreck or something?”

A few months later, during my first weekend retreat, I asked a similar question of another student, a monk who happened to be a friend of mine. I was well aware that one was not supposed to speak, but my spine was collapsing, and despite the fact that my chest appeared to be expanding and contracting, no air seemed to be reaching my lungs. Waiting in line for the bathroom, I whispered, “What do you do about posture problems?”

“See a doctor,” he snapped.

Desperate now, I signed up for a special workshop at an upstate monastery led by a disciple of Charlotte Selver. It was called “Body Awareness,” and according to the brochure it was directed precisely at the sort of posture problems one encounters in meditation. We spent a lot of time lying on the floor, trying to “feel” and “visualize” our spines while exploring the subtle paradox that permits one to hold oneself erect while “surrendering to gravity.” Sitting on zafus, we allowed ourselves all extremities of slouch, then slowly straightened ourselves, feeling our vertebrae “opening” and “breathing.” We pushed our heads upward as if holding up the sky. Investigating “the pelvic platform,” or “sitting bones,” we pulled and pushed the flesh of our buttocks so as to feel the skeleton beneath them. To “release” our breath, we used Suzuki Roshi’s well-known swinging-door image, imagining that our lower bellies were opening and closing like the door of a saloon. When the workshop ended, I was convinced I’d solved my problem, found the treasured “platform” that would make me—to use a favorite image in Zen literature—as stable as Mount Fuji on my cushion. But the next time I went to the zendo, another monitor “straightened” me, and the angle at which he left me was, if anything, more extreme than the one I’d been left at before.

Soon the grapevine brought another savior—a teacher of the Alexander Technique who was said to have studied with Suzuki Roshi himself at Tassajara. Digging her fingers into my groin, she suggested that my hips were “rotated,” my body out of line, the angle of my head and spine totally, to use her word, “fercockta.” My body and my image of it required total rehabilitation but under no condition was I to be self-critical or “goal-oriented.” We were dealing not in self-consciousness, you see, but in “awareness.” I had to learn to release my head without trying to release it. The words “forward” and “up” were bred into my mind like mantras. Instructed by means of an elaborate model of the human skeleton, I studied the hip and shoulder sockets and the point at which the spine, head, neck, and shoulders converged. Rotating my head or pulling on my thighs, she cried, “Yes! Yes!” for reasons I could not discern. With each session, I became more self-conscious about my posture. My zazen was haunted by images of my skeleton which, when I told her of them, she took as proof that her instructions were being internalized. What else should I have expected from a woman who, after attending a track meet at Madison Square Garden, said of a runner who’d broken the world’s record at 1,500 meters, “He’d do better if I could teach him how to hold his head”?

Next came yoga. An American woman who had studied with Iyengar and was said to be “a scholar of the Lotus Postures.” I took my cushion to her studio and, after watching me sit for less than thirty seconds, she advised me to give up Half Lotus forever. Mr. Iyengar, she said, believed in the Full Lotus, but not in the Half. Too much twisting of the foot, and look how it pulls that right leg forward! She pointed to the folds of my pants as an indication that the skin on my right leg was thrusting toward the knee while that of my left was being pulled in the direction of my groin. The posture recommended by Mr. Iyengar was cross-legged, with one foot below the opposite ankle and one knee maybe ten inches off the floor. I told her there was no way one could meditate for any length of time in this position, but she said I was being rigid and defensive. “Don’t you think I know about meditation? We do thirty minutes of Pranayama every day!” I told her I felt unstable, but she said that was because I was habituated to asymmetry. If your ankle hurts, she said, put a pair of socks beneath it. Put a blanket under your knee. Since the Zen mudra—hands cupped in your lap—pulls on the shoulders, put a cushion under your hands. Sit on a stack of blankets, lift yourself upward without thrusting your pelvis forward, then lower yourself slowly onto your sitting bones. Of course all this is difficult at first, but remember you have a lifetime of bad habits to change. We are literally re-constructing your body!

It was easy to escape her, but not so easy to escape my obsession with posture. By now it circumscribed my practice. All that I took to be the “higher” dharma questions were dwarfed by this issue which, given Zen’s predilection for the concrete, and my own for the abstract, was not a completely unfortunate development. When good fortune presented me with the opportunity for a private audience with the late Dudjom Rinpoche, one of the most revered of all Tibetan lamas, you can be sure it wasn’t dzogchen I asked him about. Stern-faced and ethereal, looming on a chair while I kneeled at his feet, His Holiness advised me through a translator that as far as meditation is concerned, posture is completely irrelevant. “Slouching? So what? You can sit on a chair or lie on your back. Yes, it is perfectly okay to meditate in bed.”

As I say, posture was seldom discussed around the zendos I frequented, but a great lore was collecting around it, a veritable library of strategy, mythology, and technology. We sat in front of mirrors sideways and front-on—in order to study ourselves, made it a point, in order to stretch our legs, to watch TV, or even when possible to work and eat, in Lotus postures. Several students I knew took to sitting with sandbags or five-pound weights on their knees. Feet went to sleep (from pressure, we speculated, on the sciatic nerve in the buttocks), and there were all sorts of completely ineffective techniques for dealing with them. Stick your fingernail into the bottom of your foot, bend the big toe backward till it hurts. Horror stories were told about students who got up from the cushion too soon and broke a toe or an ankle. As all of us grew more sophisticated and frustrated, there was endless experimentation with the height and firmness of one’s cushion. We learned to expand or diminish our zafus, extracting or adding stuffing (in most cases, the fiber kapok) through that neat little slit in the side, and we grasped at formulas such as “the higher the cushion, the easier on the legs and the harder on the back,” until someone else told us that the opposite was true. We bought cushions at different places because they were harder, softer, thicker, or thinner, and we even tried out those cushions the size of orange crates, called “gomdens,” which Trungpa Rinpoche, distressed by his students’ posture problems, had recently invented in Boulder. We stacked cushions on top of each other until our heads were so high that we might have been standing up, bought thin “support cushions” to slip under painful knees, alternated the Lotus with the “Burmese” posture in which the legs are folded but not crossed. Attempting the kneeling, so-called “Seiza” or “Tea” posture, in which one places the feet beneath the buttocks, we entered another maze of complication. Adepts could do it, as Asians could, without a cushion, but the tight-kneed placed one or two cushions beneath the buttocks and between the feet or, if the knees would not tolerate this angle, placed the cushion on the heels. Needless to say, this was rough on the Achilles tendons, brutal on the feet. Long sittings could leave you as numb and paralyzed as I had been after my excursion into Full Lotus. Still, it was such a useful posture for Americans that it led to the invention of the “Seiza Bench,” which located the feet beneath the buttocks but spared them the weight of the body. Some Japanese teachers are said to have collapsed in laughter at the sight of these benches, but within a year, the catalogues of meditation supply houses, more and more of which were finding their way into my mailbox, were featuring Seiza benches in different woods and finishes, some with padding and upholstery or legs that folded flat so as to make them more portable. There were also zafus with handles, zafus of many colors, zafus with zippered, removable covers, inflatable zafus, and of course, packages of kapok so one could adjust one’s cushion endlessly.

There were other misadventures. A karate master who also taught zazen told me that one should never relax on the cushion. If you did not find yourself completely exhausted after sitting, you could be sure you’d wasted your time. He directed me to “push down on the kidneys and forward with the small of the back,” but when I tried to do so, I found that I could not breathe at all. At the Zen Community of New York an expert in Shiatsu taught us how to walk on each others’ backs, creeping along the spine and pouncing like tigers when we felt tension in the vertebrae. Since comfort was not, as at other Zen centers, a negative concept here, many students used a sort of three cushion technique—meditating on chairs with one cushion beneath their buttocks, another supporting their back and another under their feet so that they looked like invalids propped up by their nurses. For a while up here I tried turning my zafu on end so that I straddled it, but I found that this cut off circulation to my genitals, leaving my penis and testicles so numb that I felt as if I had castrated myself.

By the time I arrived at Roshi’s zendo, I had studied every book I could find—Masahiro Oki’s Zen Yoga, for example, or Katsuki Sekida’s Zen Training—which explored meditation posture, taken my problem to another Alexander therapist, another Zen master who had passed through the city, a Zen monk trained in yoga, two chiropractors, and a Rolfer. An acupuncturist at one zendo had placed needles in my ear and left them there through a seven-day retreat. He had also sold me a battery-powered device the size of a fountain pen, which was supposed to cure knee pain by dousing it with negatively charged particles. All my advisers had guaranteed that they could cure my problem, but zazen continued to be painful, and I felt no less off-balance on my cushion than I had been two decades earlier, when my first encounter with the keysaku had stripped me of my innocence.

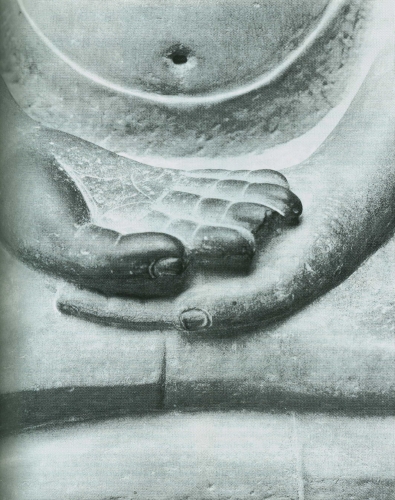

For all his laughter, Roshi’s response to my posture problem is never unsympathetic, and he is no less inclined than my other mentors to offer strategic solutions. He draws invisible diagrams on the cushion to indicate where the anus or coccyx should be located, and while I could not be sure that he was serious, I once heard him say that, if one sits properly, the anus will close, and if the student is male, his “sausage” will stand up. Once he speculated that, since my profession as a writer requires me to spend so much time in a chair, my anus and coccyx are too close together. In effect, my “pelvic platform” (he did not of course use this phrase) has shrunk so that I am round, or maybe even pointed, where I ought to be flat. Sometimes, arguing that I have become too obsessed with posture, he insists that I sit in a chair, but I find this even more difficult than sitting on a cushion. His equations are simple and always reversible: if one sits “with bravery mind,” the head is erect, less blood goes to the brain, less thought is generated, and vice versa. If the back is straight, the breath is deep and the mind calm, and if the back is bent, the breath will stop in the chest or the stomach and endless thought will arise. But over the years, as I have attended to his instructions, I have come to realize that the advice he offers today will not necessarily be offered tomorrow. One day he tells me to let breathing dictate my posture, the next to forget breathing and concentrate on keeping my back and head straight, the next to forget both breathing and posture and “breathe with whole body, in and out through every pore.” When once I complained that I was having trouble breathing, he said, “No need to breathe.” Such contradictions often make me crazy, of course (he would say, I think, that they do not make me crazy enough), but what I have gradually come to realize is that they are less a result of inconsistency than his essential attitude toward matters of technique. In effect, he is against any idealized image. Stable posture? Clear mind? Unobstructed breathing? Convinced as he is that the mind and body cannot be separated—”When you laughing,” he says, “which laughing—body or mind?”—he considers all such images, and all the technique with which we attempt to realize them, irrelevant, a sort of game one plays until the true solution is achieved. What is that solution? Knees on the floor? Back straight according to the plumb line? “Larry-san, I give you good advice,” he said to me once. “Become sincere and all your pain is gone.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.