In a 1957 address to the Music Teachers National Association of Chicago, composer and musician John Cage described experimental music as an “affirmation of life—not an attempt to bring order out of chaos nor to suggest improvements in creation, but simply a way of waking up to the very life we’re living, which is so excellent once one gets one’s mind and one’s desires out of its way and lets it act of its own accord.” While directed to a group of musicians, Cage’s encouragement to “wake up” to reality as it is may sound familiar to Buddhist practitioners.

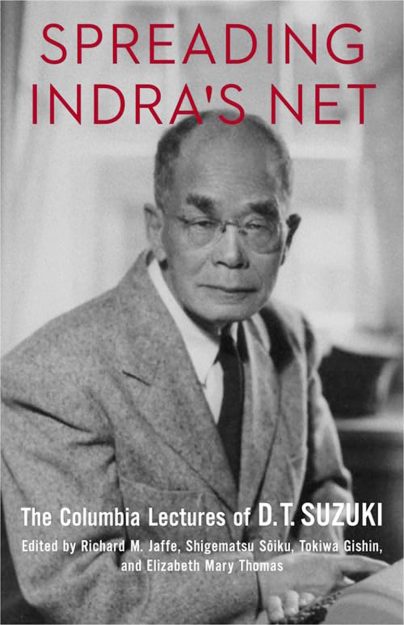

But this was no passing analogy. Just a few years earlier, Cage had attended a lecture series delivered by Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki (1870–1966), the well-known Zen layman who popularized the tradition among Western audiences during the 1950s and whose legacy remains resonant among European and North American practitioners today. Suzuki’s lectures, attended by Cage and a coterie of other artists, writers, and intellectuals residing in the New York City area during the mid-20th century, are central to Spreading Indra’s Net: The Columbia Lectures of D.T. Suzuki by Richard Jaffe, a professor of religious studies at Duke University.

Spreading Indra’s Net: The Columbia Lectures of D. T. Suzuki

edited by Richard M. Jaffe, et al.

Columbia University Press, 2025, 384pp., $35.00, hardcover

Suzuki is widely considered pivotal to the spread of modern Buddhism, especially Zen, to Europe and North America. His writings, which span more than half a century, advance a systematic view of the Mahayana tradition, its embodiment through Zen practice, and its philosophical expression in Chinese streams of Huayan thought. In comparative dialogue with Christian theology, theosophy, and psychoanalysis, Suzuki’s works reached a range of intellectuals across many fields and disciplines during the 20th century. They also found a popular audience and remain foundational for our understanding of the history of religious transmission and cross-cultural interaction in the modern era.

Jaffe offers readers a rigorously annotated set of Suzuki’s lectures delivered at Columbia University between 1952 and 1953. The lecture series provides a comprehensive view of Suzuki’s expression of Zen philosophy and its implications for practitioners. Drawing mainly from the Awakening of Faith and the Flower Garland Sutra, both foundational Mahayana texts in East Asia, Suzuki covers a range of topics across six lectures: the awakening of the Buddha, the nature of the mind and consciousness, the interpenetrative reality of being and phenomena, the role of compassion in awakening, and others. He utilizes several interrelated methods to explain Buddhist teachings: He engages his topics etymologically, often providing Sanskrit, Chinese, Japanese, and English analogs; epistemologically, especially in his comparative approach to Buddhist and Christian understandings of the mind; ontologically, in describing consciousness and its relation to the body; and morally insofar as he attends to our experience as social beings in a relational world. Taken together, the lectures stand on their own as a testament not only to Suzuki’s understanding of Zen, Huayan, and of Buddhism more generally but also to his boundless effort in explaining, analogizing, and simplifying these complex teachings—and in a language non-native to him—for audiences who had never been exposed to them before.

While the lectures offer a glimpse into the mind of Suzuki, a key strength of Jaffe’s book is his attention, in the sprawling introduction, to the social, cultural, and intellectual milieu in midcentury New York City. The author’s depiction of a vibrant and dynamic community of creators that converged around Suzuki during this lecture period, and which continued, in some cases, after he returned to Japan, gives energy to the lectures and squarely locates them in time and place. The artists and intellectuals in Suzuki’s orbit, many of whom were engaging a range of East Asian philosophical and religious traditions, constituted his core audience during this lecture series.

In the immediate postwar years, Americans renewed their interest in Japanese culture, which included an appreciation for Japanese film, literature, and fine art. In this context, and in New York City, which became one of the most active sites of artistic work in the world by the 1950s, Suzuki’s articulation of Zen drew in a large contingent of creatives and progressive thinkers. Among them were John Cage, dancer Carolyn Brown, psychoanalyst Erich Fromm, philosopher and art critic Arthur Danto, ethicist Horace Friess, painter Philip Guston, writer and humanitarian Dorothy Norman, and many others. These now-notable figures not only bore witness to Suzuki’s lectures and promoted them and their ideas but some attempted to apply key principles, as they understood them, to their life and professional works.

Suzuki is widely considered pivotal to the spread of modern Buddhism, especially Zen, to Europe and North America.

Jaffe is meticulous in tracing the intricate networks of interest, support, and favor that coalesced around Suzuki and, in so doing, reveals a man who was central to European and American religious truth seekers of the time. These people became patrons of Suzuki’s work insofar as they cleared the way for his activities at Columbia University and his rise to prominence among New York City’s intellectual community.

When Columbia administrators failed to provide funds for Suzuki to teach his courses, and when support from the Rockefeller Foundation also fell through, it was psychoanalyst Karen Horney who introduced Suzuki to Cornelius Crane and Cathalene Parker Crane, two new benefactors who agreed to pay his salary during his tenure at Columbia. The former was the nephew of philanthropist and businessman Charles Crane, who sponsored much of Suzuki’s prior travel and research and to whom Suzuki dedicated his 1938 Zen Buddhism and Its Influence on Japanese Culture. Horney, the Cranes, and key members of Columbia’s philosophy department worked administratively and financially to establish the teaching position between 1952 and 1953.

Suzuki’s teachings garnered support, but he also wielded a passive magnetism. Many supporters remarked, in their own accounts, on Suzuki’s quiet gravitas, his direct speech in closed conversations, his physical framing in a cardigan sweater and bowtie, and his prominent eyebrows, perhaps Suzuki’s marquee facial distinction. The administrative, financial, pedagogical, and interpersonal accounts of Suzuki’s supporters suggest, among many things, that they were drawn as much to the man as they were to his teachings.

Readers will note particular attention paid to the role of two women in Suzuki’s life, both of whom were instrumental in his efforts to articulate Zen for Western audiences. Egyptologist Elizabeth Thomas, whom Jaffe has designated as a coeditor, compiled a manuscript of Suzuki’s lectures from more than 1,100 pages of handwritten notes taken during her attendance of nearly all of the lectures. These notes were faithful to the lectures, though Thomas enhanced them through her clarification of dates, other students’ notes, material drawn from one-on-one meetings between her and Suzuki, Suzuki’s private talks offered to small groups, and his publications. Thomas also included her interlinear asides and elaborations on Suzuki’s lecture content, which provide a compelling introspective aspect to the lectures presented in Spreading Indra’s Net. Jaffe footnotes all of this additional material, thereby inviting the reader directly into the lecture hall and as a witness to Suzuki’s students’ great effort in digesting his teachings.

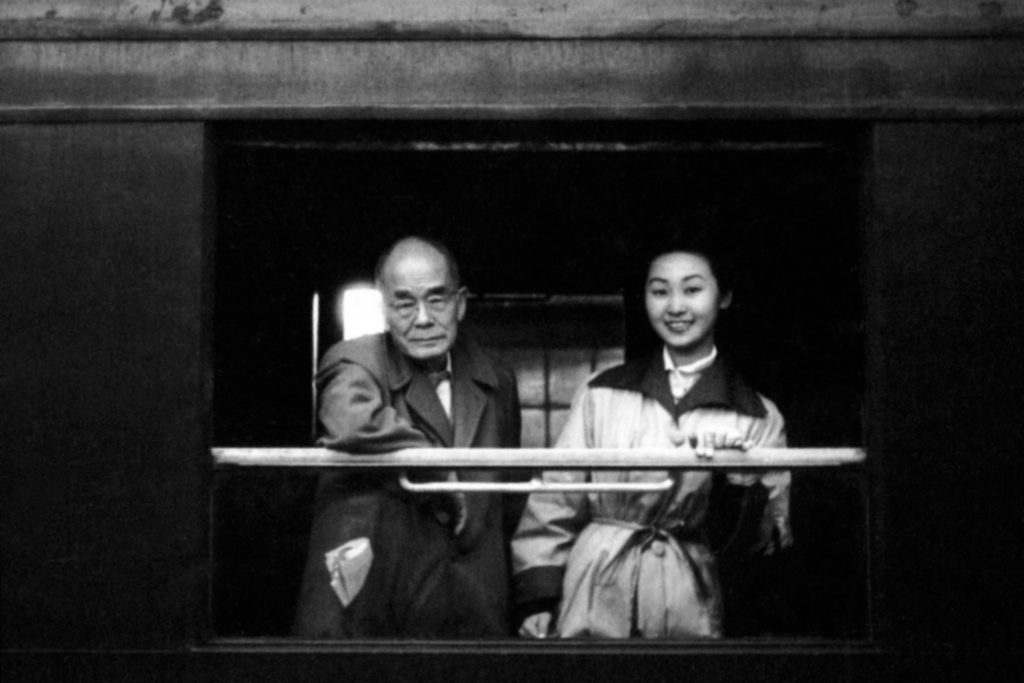

Mihoko Okamura-Bekku, Suzuki’s assistant from the early 1950s until his death, provided the clerical and domestic support necessary for Suzuki to undertake his lecture series. Mihoko attended most of Suzuki’s lectures, hosted him in her family home from early 1954 after he moved from his Butler Hall residence, accompanied him on European conference trips, and traveled with Suzuki on his return to Japan in 1959. Mihoko truly enabled Suzuki’s work throughout his seven-year stay in New York City. Her support was, therefore, just as important as the intellectual and editorial support he received from Thomas and, as Jaffe points out, was crucial to Suzuki’s sustained work, which contributed significantly to the flourishing of Buddhism in the United States.

Spreading Indra’s Net is a celebration of primary-source research and the use of archives. Supplemented with material drawn from ten physical archives across North America and Japan, the lectures are presented as a living entity. Editorial asides from the compiler of the original typeset manuscript, itself shaped by the notes and reactions of the very students who attended Suzuki’s lectures, bring them vividly to life. So, too, do the voices of midcentury New York City’s thriving community of artists and intellectuals who sought out Suzuki’s Zen. Jaffe interweaves all of this and, in this way, presents an archive of archives.

This study excavates a historical network of social, intellectual, and editorial actors who facilitated the original oral lectures and, later, the emergence of the manuscript that became the basis of this publication. Jaffe, who consulted some of these very actors and their kin about additional private holdings related to this period of Suzuki’s life, has archived the whole of this network. Suzuki is by no means an understudied figure in modern Buddhist transmission. But Jaffe’s book sharpens our understanding by focusing on the formative New York community of learners and supporters who were so captured by his teachings.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.