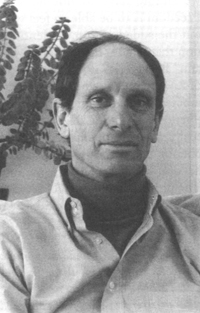

Joseph Goldstein, co-founder of the Insight Meditation Society (IMS) and the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies (both in Barre, Massachusetts), has been leading retreats in the vipassana tradition of Southeast Asia for nearly twenty years. His teachers include Anagarika Munindra, S. N. Goenka, Dipa Ma, and the Venerable V Pandita Sayadaw of Burma. He is the author of The Experience of Insight: A Simple and Direct Guide to Buddhist Meditation and co-author of Seeking the Heart of Wisdom: The Path of Insight Meditation. His new book, Insight Meditation: The Practice of Freedom, was published by Shambhala in the fall.

This interview was conducted by editor Helen Tworkov at IMS in October.

Tricycle: After leading nineteen three-month retreats, what inspires you to keep at it?

Goldstein: In the last few years I’ve taken more time, two or three months each year, to reimmerse myself in practice in an intensive way. It is tremendously energizing to reconnect to what the teaching is all about, to why I got into it in the first place.

Tricycle: What is it all about?

Goldstein: For me the Buddha’s teaching is about freedom and the qualities that come from that freedom, like kindness and compassion. I see those situations where my mind is open and spacious and responsive, and the times when my mind contracts around something. The difference between those two experiences is so clear. The possibility of freedom, though, is contingent on seeing when the mind contracts or gets distracted and lost in the story.

Tricycle: Can you give an example?

Goldstein: A simple example is when we go to the movies and become totally absorbed in the film. Then there is the moment when we step out of the theater and experience that sudden reality shift, a mini-awakening to where we really are.

In the same way we are often lost in the movies of our mind. There’s a Zen story about a hermit monk who painted a tiger on the walls of his cave. He painted it so realistically that when he finished, he looked at it and became frightened. It takes practice to wake up, to emerge from our mind-created worlds. This makes being with people and situations in a fresh way each time possible. That’s the joy of teaching and why it doesn’t get stale.

Tricycle: Do you think the American involvement with psychology makes us more attached to our stories?

Goldstein: Not really. I think it is in the nature of life itself. Basically the biggest story, the most fundamental story, is the idea of self. We weave everything around that. It’s what keeps the wheel of samsara going.

Tricycle: If a meditation teacher suggests that you set your story aside and follow the breath and relax into a kind of choiceless discrimination, and then, suddenly, tremendous psychological material comes up, what do you do with your story?

Goldstein: Perhaps a difference between the therapeutic approach and the meditative one is that in therapy one might explore the content of the story, examining the particular circumstances around the thoughts and emotions arising, while in meditation we would explore the very nature of thought or emotion. What does anger or sadness or happiness feel like? How is it manifesting? One of my early teachers, Munindra-ji, said something that has stayed with me over all these years. He said, “The thought your mother is not your mother; it is a thought.” The thought itself is insubstantial. It is our attachment to the content that makes it so solid.

Tricycle: Is there one area in which the therapeutic and the meditative processes come together?

Goldstein: There are many areas in which the two processes help one another. One, in particular, stands out. In order to free the mind from the contraction of identification with thoughts and emotions, there needs to be acceptance. If we’re not allowing ourselves to feel them, that very resistance feeds them and locks them in. If, as different thoughts and feelings arise, we have the ability to be accepting, then it is possible to approach them with a meditative perspective, simply letting them come and go. A therapeutic approach can help us become more accepting, especially with deeply rooted patterns of conditioning.

The nature of awareness is not tainted. If one is actually resting in awareness, resting in the nature of the mind then one is feeling the emotion—grief, sorrow, joy, peace—but instead of identifying with it, the mind simply rests in the awareness of whatever arises.

Tricycle: In that resting there’s no suggestion that we should let go of the feelings themselves?

Goldstein: We don’t have to let go, we simply have to not hold on. Freedom is to be able to feel without the added notion of identification that “this is me,” “this is who I am.” Because it’s not. A phrase one of my teachers used to describe the meditative experience is “empty phenomena rolling on.” And that’s really what’s happening. It’s empty phenomena with no one behind it, no one to whom it is happening. The problem is that we get attached or react in aversion and that’s where we get caught in the story.

Tricycle: Did your understanding of self and story come through Buddhism alone? Or can you look back to other experiences that were congruent with Buddhist training?

Goldstein: When I was in the Peace Corps in Thailand and just getting into practice, I was reading Proust’s A Remembrance of Things Past, and some of the Pali canon at the same time. Basically the insight that Proust had, which inspired his masterpiece, was that the past is in the present. The only way we know the past is as an experience in the present moment. A thought, a smell, a memory is something happening right now that we are calling “past.” We don’t experience the past outside the thought of the present moment. Then my mind made this jump. Well, if the past is like that, that must be what the future is like, too. There is just the thought in the moment. The whole burden of past and future, of time, of time-created stories, all collapsed into a simple thought in the moment. To relate to the moment is so simple. If we try to relate to the past, it’s huge. It gets back to the whole question of psychology and dharma. Past and future make up our stories.

From that moment on my life became so much simpler. The same thoughts and feelings came up, but I was able to see them as being a thought in the moment, rather than shouldering the weight of my whole past life or all the anxieties about my future.

Tricycle: The householder life is very common in American dharma practice, yet this is quite different from Asia. Does the lifestyle affect the practice?

Goldstein: A friend went to see a Tibetan lama in Nepal and asked how he could become liberated as a householder. Rinpoche replied, “Even the Buddha had to renounce the household life.” This has to do with renunciation, because on many levels, renunciation is what frees the mind: renunciation of grasping, renunciation of our attachments.

Tricycle: Where does that leave us?

Goldstein: For me this is the dilemma of coming back to the West both in terms of teaching and of continuing my own practice. The ongoing challenge for Westerners is to find a way to bring that power into the life of the layperson. One way is through the retreat setting, because for that period of time a significant amount of renunciation takes place. Because of the constraints in peoples’ lives, some can do a weekend, ten days, three months. A surprising number of students here have done many three-month retreats, which in our culture is unusual. I think they’ve been motivated because it offers a genuine taste of the monastic experience, and the power that can come from it.

Tricycle: Do you still feel a difference between your daily life as a layperson and as retreatant?

Goldstein: Yes. One of the things I love most about being on retreat is the silence. Because I’m teaching and speak with people a lot, the contrast of being in silence is both restful and inspiring. As a corollary to that, I find that when I’m on retreat I don’t waste time. I know just what I’m doing and the situation is conducive to my doing it. There’s the sense that from the time of waking up in the morning to the time of going to sleep, my only job is to really pay attention.

Tricycle: The idea that the householder lifestyle can be made comparable in power and practice to traditional monasticism is becoming more and more popular. Do you think that’s possible?

Goldstein: Possible, but rare. There have been cases of great enlightened masters as householders. But it’s not common. As householders we’re busy and we have a lot of responsibilities, and the work of dharma takes time. The view that it’s as perfect a vehicle as monasticism doesn’t accord with what the Buddha taught. He was very clear in the original teachings that the household life is “full of dust.” But since we don’t have a monastic culture in America, the great challenge is how to achieve liberation as laypeople. We need to look at the degree to which we are willing to make our life our practice—not just as words but in the actual choices we make. One of the beautiful things about the teachings is that the Eightfold Path is very explicit. It lays out what we need to do. We have to honestly ask ourselves what our priority is. Is it awakening? Or is dharma practice something I do simply to keep me cooled down?

Tricycle: Do you think not having a vital monastic establishment will affect the level of teachers and practitioners in the West?

Goldstein: Well, I wonder whether we, as a generation of practitioners, are practicing in a way that will produce the kind of real masters that have been produced in Asia. I don’t quite see that happening—although there may be people leading reclusive lives that have that level of realization. Dialogue about that among Western teachers would help us to see what conditions we need to create for people to reach those levels of realization, of mastery.

Tricycle: Do you think the obstacles to that kind of mastery in this country are different than they were, or are, in Asia?

Goldstein: Yes. That intense devotion to practice has traditionally happened in the context of monasticism, where there was the support for the long sustained effort. We don’t have that support system as yet in our culture, and even if somebody wanted to spend a lifetime in practice, unless they were independently wealthy it would be hard to do.

Tricycle: Many Buddhist feminists fault the Buddha for abandoning his wife and child—his householder life—to seek enlightenment

Goldstein: That’s a confusion of levels.

Tricycle: What do you mean?

Goldstein: My Burmese teacher U Pandita talked about making a distinction between dharma values and human values. Although they often overlap, there are appropriate choices and decisions to be made in each of those realms. In the realm of human values, one would not renounce one’s family to go off to become a Buddha, because in the realm of human values the greatest value is placed on human relationships. In the realm of dharma values the greatest value is placed on awakening, on enlightenment, and that’s the reference point for the choices that one makes. I think there are skillful ways of going between these two realms.

To fully comprehend the story of the Buddha and his renunciation of the householder life, it would be necessary to understand the evolution over lifetimes of the Bodhisattva, and those of his wife, Yasodhara, who had mutual aspirations, for many, many lifetimes. This was not a sudden decision, “Okay, I’m splitting.” This was the fruition for both of them of many lifetimes of aspiration. That action can’t be separated from the power of the Buddha’s motivation. It was an act of renunciation to benefit all sentient beings, done for the accomplishment of the supreme good. In the case of the Buddha the power of that action is still benefiting beings all these centuries later.

Tricycle: In terms of human values and dharma values, where do you place Buddhism in America?

Goldstein: I think that we often practice the dharma in service of human values.

Tricycle: For what reason?

Goldstein: Perhaps many people haven’t met teachers who have completely realized the truth, teachers who might inspire them to something greater, more transcendental.

Tricycle: Americans do seem to want to humanize the spiritual realm.

Goldstein: The degree to which we have been inspired to the possibility of freedom and awakening is a direct result of the great teachers that we’ve met. That’s why I feel it’s so important for us to continue deepening our practice. Many of the teachers in the West have a genuine level of realization and have a great deal to offer but may not yet be fully cooked. I certainly feel that way about myself.

Tricycle: Do you think the teachers themselves are practicing enough?

Goldstein: I don’t monitor people’s lives and practices, so I really don’t know. I haven’t yet met fully accomplished Western dharma masters. Or maybe I’ve met them and have not recognized them. But even if only a few in every generation come to full realization, that would be a great thing.

Tricycle: What chance do we have of maintaining the true dharma if we have generations of half-cooked understanding?

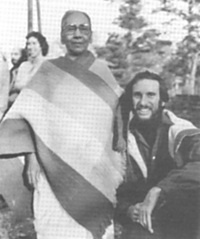

Joseph Goldstein and Dipa Ma in the late 70s in Barre, Massachusetts

Goldstein: That’s a real question. I wonder how much connection there will be to an authentic lineage of awakening in another twenty years. The amount of time that people spend training to be a teacher is getting less and less. In Asia, people will often practice for as many as ten or twenty years before teaching. Most of us who came from practice in Asia to the West started teaching much sooner than that but it was still after a substantial period of training. There are people teaching now who have practiced for only a few years. This may be because of the tremendous need. If we want to embody the highest values of awakening, our own continued practice is an essential aspect of what we as teachers need to do. If we don’t, Buddhism in America might easily become a sideshow of the self-help culture. We need to keep our practice going in order to fully realize liberation, to transcend the notion of self altogether. For me, taking time to go on retreat means turning down requests to teach. For some time it felt too selfish, and I wondered why I should go on retreat myself when I could be helping other people. But then I thought, At what level am I serving? If we don’t continue to deepen our own realization, we’re abdicating a tremendous responsibility in the transmission of the dharma because what will come after us depends on our own level of wisdom and understanding.

Tricycle: Where are you in your own practice?

Goldstein: I’ve seen certain qualities like concentration and mindfulness, loving-kindness and compassion, grow much stronger over the years. And when my mind contracts, gets caught by desires or moments of irritation, I experience it quite viscerally as a contraction of energy. It can be a fleeting identification with a momentary thought. It can be an identification with a stronger emotion or with a mini-drama. But now all of that happens in a context of greater spaciousness, nonjudgment, and acceptance. Experiencing this change gives me tremendous inspiration to continue my practice. There is one phrase that many of the enlightened ones from the time of the Buddha used to express their realization: “Done is what had to be done.” Can we each practice to that place of completion?

Tricycle: Is there still a distinction between when you are sitting and when you are not sitting?

Goldstein: In one way there is and in one way there’s not. The way in which there is no distinction is that the nature of awareness doesn’t change and what one is being aware of doesn’t change. What’s quite strange and sometimes surprising is that there are really only six things we ever experience: sight, sounds, smells, taste, bodily sensations, and objects of mind—thoughts, emotions, internal conditions. We have innumerable concepts and stories about these six basic kinds of experience, but when you get down to a meditative quality of awareness it comes down to these. So, nothing different happens when you are sitting in the hall or walking down the street. But in intensive practice, because we have simplified our body movements and employed tools to steady the mind, our awareness becomes much less distracted. We’re not so pulled into our own experience. When a thought comes, rather than being carried away by the thought, the thought is liberated and the mind stays free. It’s the ultimate radical act. If we are not aware of what is going on, particularly in our minds, if we are not aware of our thoughts or emotions, what happens? We act them out with no space for discriminating awareness. When we look at all the suffering in the world, where is it coming from? The great illumination in practice is that it is not just out there. It is not just happening in Bosnia, it is happening in us. We may not be acting out in quite such a visible way, but we are acting out in terms of relationships with other people, in terms of how we feel about ourselves.

Tricycle: Yet there seems to an increasing interest among Buddhists in Asia and America to work with problems “out there.”

Goldstein: Meditation is not a hobby. It is important to address the problems of the world, of our society, to express our understanding through compassionate action. But if the world is truly to be a place of peace then we need to understand our own minds. Because what is happening “out there” is simply a manifestation of what is happening in the mind.

When we see for ourselves quite immediately, clearly, decisively, the momentary nature of all phenomena, we are released from the grip of attachment and we begin responding rather than reacting. Meditation practice takes us from the very beginning stage of calming the mind to the highest experience of enlightenment.

Tricycle: Are we in danger of losing that experience?

Goldstein: Western culture in general, and America in particular, has such an emphasis on instant gratification, on “I want it now.” We once got a letter to IMS addressed to the Instant Meditation Society—basic Freudian slip. The idea of practicing over the long haul is a process of awakening, not a question of a weekend enlightenment intensive. There is the initial connection and then a real ripening. It’s a challenge to inspire people to the necessary commitment to practice that is needed to actualize that ripening. It would be sad if in the course of the transmission from East to West we lost the very essence of what dharma is all about—which is awakening, not simply feeling better.

Tricycle: Considering that you refer to yourself as midway, can you take a student further than you are?

Goldstein: I’ve had teachers whose students—even as they were their students—had greater realization. That’s a result of the skill of the teacher. So it’s possible. But it is important for students to know that different people have varying degrees of realization. The Buddha taught about different stages of enlightenment. And in each of the traditions—Zen, Vajrayana, Theravada—there are a lot of maps of the stages of development that people go through. People do notice that teachers are at different levels. Students tend to be drawn to teachers who can take them on to the next step, or the missing piece. They may be with somebody up to a certain point and then if their aspiration is sincere, dharma force will lead them to the next person to help them.

Tricycle: What are the qualities that the West brings to dharma practice that are particularly useful?

Goldstein: I often think of the Missouri take on things—the “show me” approach—as very American. Not accepting things just because they are traditional is a very healthy quality. I think this fresh testing of the dharma is very much in accord with the Buddha’s instructions in the Kalama Sutta. Even back then, as he said, there are so many teachers, who should we believe? And the Buddha said, Don’t believe in me, don’t believe in others, don’t believe in something because it is written in books, but really see for yourself what practice is conducive to the weakening of greed and delusion. From the very beginning this pragmatism was in the teaching, and I think Buddhism in the West is coming back to that. If enlightenment can actually be the polestar of our practice, then I have a great faith in the unfolding of the dharma in the West. We are just at the beginning.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.