On Saturday, September 14, 1991, the American poet Philip Whalen, known also by his Buddhist name Zenshin Ryufu, was installed as abbot of the Hartford Street Zen Center in San Francisco. An assembly comprised of Zen practitioners in black robes, ranking arhats, and bodhisattvas from both Zen and Vajrayana Buddhist traditions, poets in blue jeans and boots, long-time friends, local chroniclers, disciples from Hartford Street’s AIDS hospice, were present for the ceremony in the basement meditation hall. Zenshin formally accepted the Abbot’s seat, staff, and horse-tail fly whisk with the words, “The seat is empty. There is no one sitting in it. Please take good care of yourselves.”

As a Buddhist teacher Philip Whalen keeps a subdued profile, serving more as an example to a few fellow practitioners than as a formal instructor. It was not until 1987 that he left his own teacher Richard Baker Roshi, who in Whalen’s brisk telling of it said, “Alright, go away and do something, go away and do your own thing. Good-bye.”

It would seem that Whalen’s thing is to sit, to sit early and late, to open the zendo at Hartford Street, ring the bells, perform bows and ceremonial functions, and otherwise go about the quiet work of naturalizing Buddhism to American soil. He insists on formal sitting practice and regards it as the specifIc imperative for American Zen. “As far as meditation is concerned,” he said at a Green Gulch Zen Center conference in 1987, “I’m a professional. I’ve been a professional since 1973. And that’s my job. I find it very difficult to sell.” He has no books of dharma talks, few students, and avoids the circuit of Buddhist teachers and institutions.

What then are his teachings? Though he won’t acknowledge his poems as a teaching device, resisting the suggestion that they embody contemplative states of mind, they are packed with that strict wild Zen humor, enough to make the buddhas of old slap their thighs. In conversation and in dharma talks Whalen invokes Gertrude Stein, who insisted that writing is “Beginning again and again, always beginning again.” Writing has been Whalen’s long-held passion. “Jack Kerouac said that writing is a habit, like taking dope. Well I have a writing habit, and I have a sitting habit.” And though any who know Whalen’s writings or reputation have come to them through his legendary friendship with better known colleagues like Kerouac, the lineage he belongs to is ancient and precise.

I praise those ancient Chinamen

Who left me a few words,

Usually a pointless joke or a silly question

A line of poetry drunkenly scrawled on the margin of

a quick

splashed picture—bug, leaf,

caricature of Teacher

on paper held together now by little more than ink

& their Own strength brushed momentarily over itTheir world and several others since

Gone to hell in a hand basket, they knew it—

Cheered as it whizzed by—

& conked out among the busted spring rain

cherryblossom winejars

Happy to have saved us all.

Born in Portland, Oregon in 1923, then raised in The Dalles, a little town up the Columbia River, Whalen was drafted during World War II into the U.S. Army Air Corps as a radio operator. As he tells it in his book The Wall, he spent several years lying in the glass-bottomed hull of a fighter-bomber, hurtling over the California deserts, reading the books of Thomas Wolfe and imagining that, could he himself write novels like those, he might achieve fame and riches. A friend of his saved us all from a shelf of such epics by placing in Whalen’s hand a book by Gertrude Stein, which catapulted him into twentieth-century modernism.

After the war, out of money and wanting time to write, Whalen signed up for college under the GI Bill. He returned to the Northwest in 1946 to attend Reed College in Portland, spending his government checks on books and staying home to read. By this time considering himself a poet, he took a house with Lew Welch and Gary Snyder—Snyder recalls that the first practicing poet he met was Philip Whalen. Whalen had been studying Hindu texts since high school and had investigated a variety of religions. But according to Whalen, his interest in Zen began with Gary Snyder’s discovery of R. H. Blyth’s four-volume set of haiku translations that came out in the fifties. Blyth keeps referring to Suzuki Daisetz in his notes.

That’s how Gary got to looking up the Essays in Zen Buddhism. So we read all those, Suzuki’s three volumes, but it pretty much started with the haiku translations.

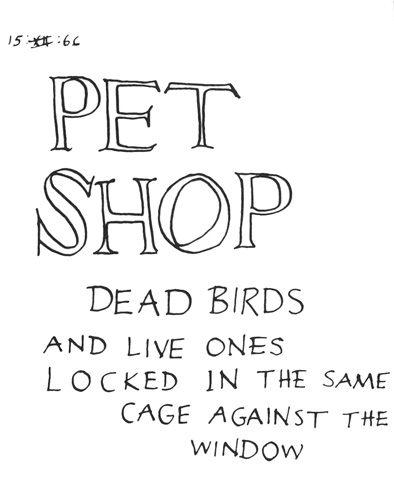

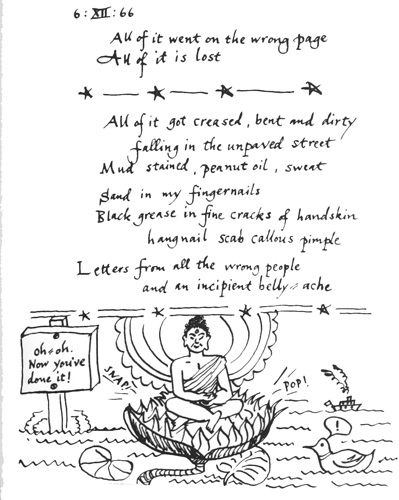

Lloyd Reynolds, one of Whalen and Snyder’s teachers at Reed, held a passion for Western-style calligraphy based on a sixteenth century Italian model, and was training his students to work with pen and ink. Whalen began to fill up notebooks in his own distinct hand, doodling and drawing his way into poems like an Oriental painter-poet, each word an exercise in attention as he moved the nib of a calligraphy pen—a practice that stayed with him. Over the years he’s pieced together massive layered poems from these quick humorous notebook pages—pages that resemble Hakuin Zenji’s irreverent poem-scrawls, or the illuminated manuscript of some whiskey-mad Irish monk—words inseparable from the gesture that freed them.

A line of poetry drunkenly scrawled on the margin of

a quick

splashed picture—bug, leaf,

caricature of Teacher.

College finished, Whalen drifted down the coast to in Francisco along with his friends, writing verse and working odd jobs, including a series of summers for the forest service back in the Northwest. Along the way he befriended Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Kenneth Rexroth, joining them for the legendary reading at the Six Gallery in 1955 where Ginsberg first read “Howl” and an excitable Kerouac passed the hat for wine. He divided the next eighteen years between Japan and San Francisco, teaching English to Japanese students, studying Zen, writing copiously, seeing several books of poetry and a novel into print—and sitting. In Japan he observed Zen monks practicing their traditional way—the vows, the fierce good-humored work, the ungarished ceremony. Their discipline attracted him.

Zen seemed to cut away many extravagances and get down to the point of emancipation and energy and cutting loose from all your emotional problems. Everything that used to hang you up goes away or at least you can deal with it in some other way….In Zen there is a great deal to understand—the long historical tradition, the connections with the various sutras and so forth—but the Zen experience cannot be explained, you have to be it, you have to practice it.

When Whalen returned to North America for good, Richard Baker Roshi, dharma heir of Suzuki Roshi, formally accepted him as a student. Whalen received the Buddhist name Zenshin Ryufu, and on February 3, 1973, at San Francisco Zen Center, Baker Roshi ordained him Unsui, Zen Buddhist monk. Whalen’s cranky, intimate, wise poetry draws freely on the old Zen tradition, rooted in India and China, never indulgent, contantly testing its own limits.

Ginkakuji Michi

Morning haunted by the black dragonfly

landlady pestering the garden moss

10:v:66

So do poets keep company with demons, as the Japanese poet Ikkyu playfully charged? Is the passion for language a devious snare? What can you get out of books? Only the over sophisticated could miss Whalen’s impeccable answer, given in dharma combat to William Butler Yeats.

Homage to WBY

after you read all them books

all that history and philosophy and things

what do you know that you didn’t know before?Thin sheets of gold with bright enameling

23:xi:63

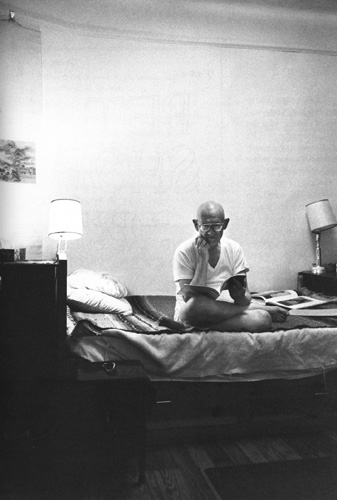

The only solid literary portrait of Philip Whalen occurs in Kerouac’s Desolation Angels, and in Big Sur, an account of Kerouac’s alcohol breakdown. Unique among the raging poets, reckless travelers, suicidal girls, tough women, and down and out hobos that populate Kerouac’s books, Whalen is drawn as a portly, sweet poet who goes by the name Ben Fagan. In one passage, Kerouac caught in the throes of alcohol-derangement passes out in a San Francisco park. Whalen calmly seats himself in the lotus position to watch over his helpless companion. Six hours later when Kerouac wakes up, his angelic guardian smiles at him, having not shifted his posture. Not the amphetamine, sex, and automobile stuff out of which you build culture heroes for young readers. No. A portrait rather, edging towards that calm robed figure in a tanka painting, standing among a host of consumptive ghosts, who extends a gentle finger towards the moon of enlightenment.

In Heavy Breathing, a collection of three smaller books of cranky Zen inspired poetry, Whalen chooses a name that refers first to a stipulation in the meditation hall that one breathe lightly (as a gesture of courtesy to one’s fellow creatures assiduously working out their salvations on neighboring cushions) and also to the necessity in out-of-hand political situations that we bring an urgent message to a world grown numb. Whalen’s poetry arrives as a deliberate disturbance in the shrine room—knocking the statues over, feeding the offerings to a hungry child—or more troublesome yet, breathing heavily as though something’s the matter.

If Socrates and Plato and Diotima

And all the rest of the folk at that party

Had simply eaten lots of food and wine and dope

And spent the entire weekend in bed together

Perhaps Western Civilization

Wouldn’t have been such a failure?

Taking stock of fellow writers like Kerouac, Whalen has noted the appearance in America, since the days of Thoreau and Emerson, of the “erratic practitioner.” They are

erratics, he says—citing a technical term for those huge puzzling rocks left behind aeons ago when a glacier passed through. And Whalen speaks of friend and fellow poet Lew Welch, dead twenty years now. Welch would practice zazen on an immense rock off the shore of Muir Beach, or load a typewriter and a bundle of books into his rucksack and strike off into the mountains in search of a remote cabin, to meditate, study, and write. “That sort of individual, hermit, erratic practice, is something that’s really important. The danger of Zen centers or monasteries is that people will take them seriously as being real. We should discover somehow that we don’t need official institutions.”

That’s the thorny contemplative speaking, who needs no more than a reed mat to sit on. It’s the poet speaking as well. There is a luminous body poets inhabit—a body of words, free as the buddhas of old, in which they pass through the world. Kerouac left this portrait of Philip Whalen—

There he sits crossleggd, leaning slightly to the left, flying softly through the night with a Mount Malaya smile. He appears as a blue mist in the huts of poets five thousand miles away. He’s a strange mystic living alone smiling over books…

The following two poems are from Heavy Breathing: Poems 1967-1980 (Four Seasons Press).

The Bay Trees Were About to Bloom

For each of us there is a place

Wherein we will tolerate no disorder.

We habituallv clean and reorder it,

But we allow many other surfaces and regions

To grow dusty, rank and wild.So I walk as far as a clump of bay trees

Beside the creek’s milky sunshine

To hunt for words under the stones

Blessing the demons also that they may be freed

From Hell and demonic being

As I might be a cop, “Awright, move it along, folks,

It’s all over, now, nothing more to see, just keep

Moving right along”I can move along also

“Bring your little self and come on”

What I wanted to see was a section of creek

Where the west bank is a smooth basalt cliff

Huge tilted slab sticking out of the mountain

Rocks on the opposite side channel all the water

Which moves fast, not more than a foot deep,

Without sloshing or foaming.

Tassajara, 11:ii:79Chanson d’Outre Tombe

They said we was nowhere

Actually we are beautifully embalmed

in Pennsylvania

They said we wanted too much.

Gave too little, a swift hand-job

no vaseline.

We were geniuses with all kinds

embarrassing limitations

O if only we would realize our potential

O if only that awful self-indulgence

& that shoddy politics of irresponsibility

O if only we would grow up, shut up, die

& so we did & do & chant beyond

the cut rate grave digged by

indignant reviewers

O if we would only lay down & stay

THERE—In California, Pennsylvania

Where we keep leaking our nasty radioactive

waste like old plutonium factory

Wrecking your white expensive world

Tassajara, 27: iii: 1979

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.