When news of the impending death of a beloved and esteemed teacher swept through the village, well-wishers gathered to pay their last respects and honor him. Standing around the master’s bedside, one by one they sang his praises and extolled his virtues as he listened and smiled weakly. “Such kindness you have shown us,” said one devotee. Another extolled his depth of knowledge, another lamented that never again would they find a teacher with such eloquence. The tributes to his wisdom, compassion, and nobility continued until the master’s wife noticed signs of restlessness and kindly asked his devotees to leave. Turning to her husband, she asked why he was disturbed, remarking upon all the wonderful tributes that had showered him. “Yes, it was all wonderful,” he whispered. “But did you notice that no one mentioned my humility?”

The conceit of self (mana in Pali) is said to be the last of the great obstacles to full awakening. Conceit is an ingenious creature, at times masquerading as humility, empathy, or virtue. Conceit manifests in the feelings of being better than, worse than, and equal to another. Within these three dimensions of conceit are held the whole tormented world of comparing, evaluating, and judging that afflicts our hearts. Jealousy, resentment, fear, and low self-esteem spring from this deeply embedded pattern. Conceit perpetuates the dualities of “self” and “other”—the schisms that are the root of the enormous alienation and suffering in our world. Our commitment to awakening asks us to honestly explore the ways in which conceit manifests in our lives and to find the way to its end. The cessation of conceit allows the fruition of empathy, kindness, compassion, and awakening. The Buddha taught that “one who has truly penetrated this threefold conceit of superiority, inferiority, and equality is said to have put an end to suffering.”

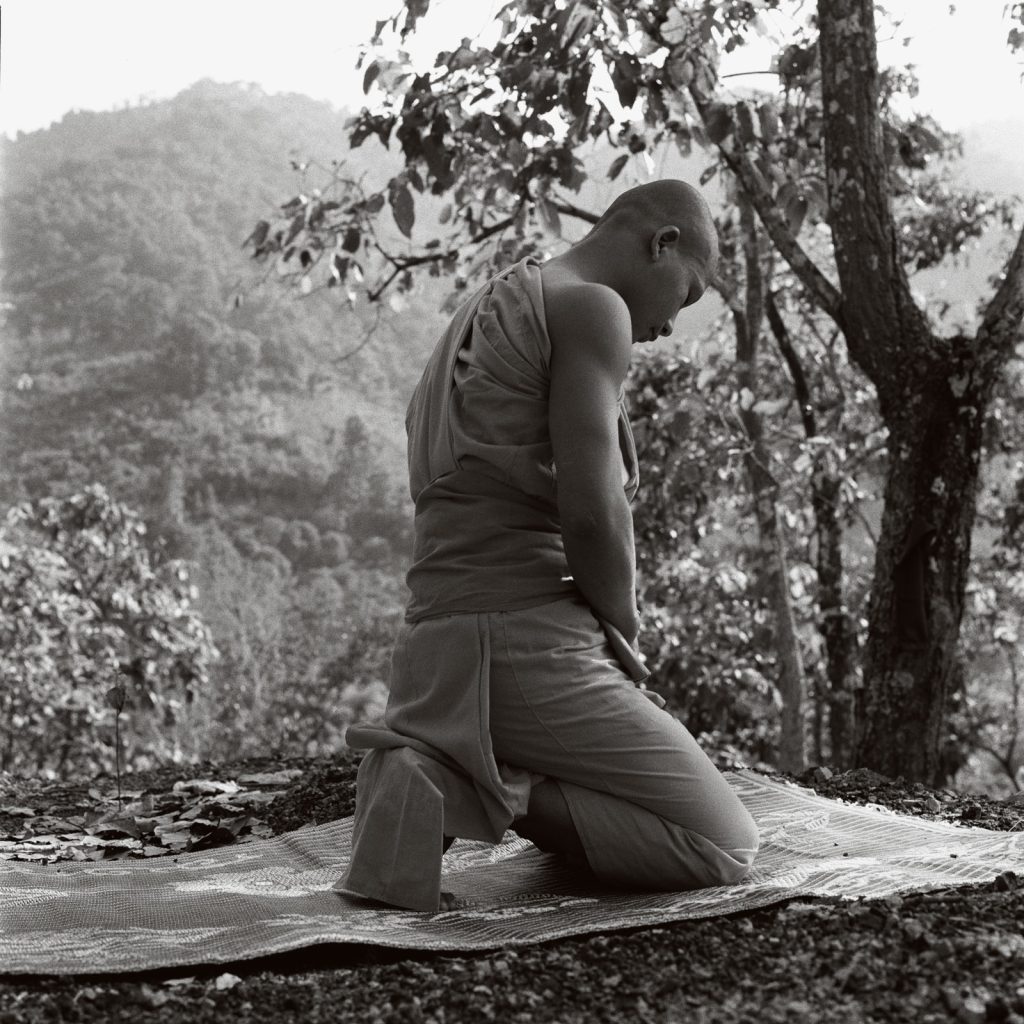

Although I didn’t recognize it at the time, my first significant encounter with conceit happened in the very beginning of my practice in the Tibetan tradition, a serious bowing culture. I’m not talking about a tradition that just inclines the head slightly, but a culture in which Tibetans undertake pilgrimages of hundreds of miles doing full prostrations the entire way. In Tibetan communities the serious bowers can be spotted by the callous in the center of their forehead. Walking into my teacher’s room in the Himalayan foothills for the first time, I found myself shocked to see people prostrating themselves at his feet. My reaction was visceral; I saw their bowing as an act of self-abasement, and I determined never to do the same. My conceit appeared in the thoughts that questioned what this plump, unsmiling man swaddled in robes had done to merit this attention. The recurrent words “I,” “me,” “better,” “worse,” “higher,” “lower,” “worthy,” and “unworthy” provided fuel for plenty of storytelling and resistance.

Over the years, as my respect and appreciation for this teacher’s generosity, kindness, and wisdom grew, I found myself inching toward a bow, often a token bow with just a slight bob of my head. Occasionally I would engage in a more heartfelt bow born of deeper gratitude, but still an element of tension and withholding remained. I continued to practice in other bowing cultures. In Asia, I witnessed the tradition of elderly nuns with many years of practice and wisdom kneeling before teenage monks who had yet to find the way to sit still for five minutes. In Korea, I saw a practice environment where everyone bowed to everyone and everything with respect and a smile. It dawned on me that bowing was not, for me, just a physical gesture, but rather an object for investigation and a pathway to understanding conceit. The bow, I came to understand, was a metaphor for understanding many aspects of the teaching—pride, conceit, discriminating wisdom, and self-image.

My first challenge on this journey was to distinguish the difference between a bow as an act of letting go of conceit and a bow that reflected belief in unworthiness. As Kate Wheeler once wrote in this magazine, “A true bow is not a scrape.” Many on this path—both men and women—carry a legacy of too many years of scraping, cowering, and self-belittlement, rooted in belief in their own unworthiness. The path to renouncing scraping can be long and liberating, a reclaiming of dignity, and a letting go of patterns of fear. Discriminating wisdom, which we are never encouraged to renounce, clearly understands the difference between a bow and a scrape. A true bow can be a radical act of love and freedom. As Suzuki Roshi put it, “When you bow there is no Buddha and there is no you. One complete bow takes place. That is all. This is nirvana.”

Conceit manifests in the ways we contract around a sense of “self” and “other”; it lies at the core of the identities and beliefs we construct, and it enables those beliefs to be the source of our acts, words, thoughts, and relationships. Superiority conceit is the belief in being better or worthier than another. It is a kind of conceit that builds itself upon our appearance, body, mind, intelligence, attainments, stature, and achievements. It can even gather around our meditative superiority. We see someone shuffling and restless on their meditation cushion and then congratulate ourselves for sitting so solidly. We might go through life hypercritical, quick to spot the flaws and imperfections in others, sure we would never behave in such unacceptable ways.

Superiority conceit is easily spotted when it manifests in arrogance, bragging, or proclaiming our excellence to the world. On retreat we may find ourselves rehearsing the conversations we will have with our partner, recounting our trials and triumphs, but especially our heroism in completing the retreat where others failed. We can feel remarkably deflated when his only interest is when we’re going to take out the garbage. It can be subtle in our inner beliefs in our specialness, rightness, or invulnerability. Superiority conceit looks like a safer refuge than inferiority conceit (thoughts of being worse than another), but in truth both cause the same suffering. Feelings of superiority have the power to distort compassion into its near enemy, pity, and to stifle the capacity to listen deeply. Superiority conceit disables our receptivity to criticism because we become so convinced in the truth of our views and opinions.

A true bow can be a radical act of love and freedom.

A traditional Buddhist story tells of the time after the Buddha’s death when he descended into the hell realms to liberate all the tormented beings imprisoned there. Mara (the personification of delusion) wept and mourned, for he thought he would get no more sinners for hell. The Buddha said to him, “Do not weep, for I shall send you all those who are self-righteous in their condemnation of sinners, and hell shall fill up again quickly.”

Inferiority conceit is more familiar territory for many of us, probably because a chronic sense of unworthiness is so endemic in our culture. The torment of feeling worse than others and not good enough is the daily diet of inferiority conceit. A student on retreat came in distress to report that none of her more familiar dramas and agitation were appearing, and she was convinced she was doing something wrong. The teacher suggested that this odd experience could actually be one of calmness and was surprised when the suggestion was met with even more distress and denial, with the student exclaiming, “Calm is not something I can do.” Another student experiencing rapture in her practice continued to assert that it was menopausal flashes, unable to accept that she could experience deep meditative states. Inferiority conceit gathers in the same places as superiority conceit—the body, mind, and appearance, as well as in the long list of mistakes we have made throughout our lives.

Inferiority conceit is fertile in its production of envy, resentment, judgment, and blame, which go round and round in a vicious circle of storytelling, serving only to solidify our belief in an imperfect self. This belief is often the forerunner of scraping as we create heroes and heroines occupying a landscape of success and perfection we believe to be impossible for us.

Governed by inferiority conceit, we may be adept at bowing to others, yet find it impossible to bow to ourselves, to acknowledge the wholesomeness and sincerity that keep us persevering on this path. Learning to make that first bow to ourselves is perhaps a step to realizing that a bow is just a bow, a simple gesture where all ideas of “self” and “other,” “worthy” and “unworthy,” fall away. It is a step of confidently committing ourselves to realizing the same freedom and compassion that all buddhas throughout time have discovered; it is acknowledging that we practice to be liberated. We practice because it seems impossible; we practice to reclaim that sense of possibility. We learn to bow to each moment knowing it is an invitation to understand what it means to liberate just one moment from the burden of self-judgment, blame, envy, and fear. Letting go of inferiority conceit awakens our capacity for appreciative joy and reclaims the confidence so necessary to travel this path of awakening.

Related: Freedom’s Just Another Word

Seeing the suffering of superiority and inferiority conceit, we might be tempted to think that equality conceit is the middle path; however, a closer look shows us that it is more a conceit of mediocrity and minimal expectations. Equality conceit is when we tell ourselves that we all share in the same delusion, self-centeredness, and greed, that we all swim in the same cesspool of suffering. We see someone falling asleep on their cushion and feel reassured. We observe a teacher dropping their salad in the lunch line, and it confirms our view that people are essentially and hopelessly mindless. Sameness can seem both comforting and reassuring. Thinking that others are also struggling on the path can make us feel relieved of the responsibility to hold aspirations that ask for effort and commitment.

Equality conceit can express disillusionment with human possibility. When we look at those who appear happier or more enlightened than ourselves and primarily see their flaws, we are caught in equality conceit. We see those who seem more confused or deluded than ourselves, and we know we have been there. We see our own delusions and struggles reflected in the lives of others and think that we are relieved of the task of bowing. The offspring of equality conceit can be a terminal sense of disappointment, resignation, and cynicism. After Al Gore’s documentary, An Inconvenient Truth, was released, several newspapers responded by publishing the electric bill of his home. What wasn’t mentioned was how the home’s electricity was generated by solar power. It seemed there was a driving need to reduce his message and show that we’re all hopeless carbon emitters.

All forms of conceit give rise to the endless thoughts and storytelling that solidify the beliefs we hold about ourselves and others. Liberating ourselves from conceit and the agitation it brings begins with our willingness to sensitize ourselves to the subtle and obvious manifestations of conceit as they appear. The clues lie in our judgments and comparisons, the views we construct about ourselves and others. Suffering, evaluating, envy, and fear are all signals asking us to pause and listen more deeply. We learn to bow to those moments, knowing they are moments when we can either solidify conceit or liberate it. Instead of feeding the story, we can nurture our capacities for mindfulness, restraint, and letting go. Instead of volunteering for suffering, we may be able to volunteer for freedom. It is not an easy undertaking, yet each moment that we are present and compassionate in the process of conceit building is a moment of learning to bow and take a step on the path of freedom.

Life is a powerful ally because it offers us the opportunities to let go of the conceit of self. There are times when our world crumbles. Unpredictable illness and other hardships come into our lives, and we face the reality once more that we are not in control. Sometimes there is simply no more that “I” can do. In those moments, we can become agitated or we can acknowledge that we are meeting the First Noble Truth: at times there is unsatisfactoriness and suffering in life. When we face the limitations of our power and control, all we can skillfully do is bow to that moment. The conceit of self is challenged and eroded not only by the circumstances of our lives but also by our willingness to meet those circumstances with grace rather than with fear.

A teacher was asked, “What is the secret to your happiness and equanimity?” She answered, “A whole-hearted, unrestricted cooperation with the unavoidable.” This is the secret and the essence of a bow. It is the heart of mindfulness and compassion. To bow is to no longer hold ourselves apart from the unpredictable nature of all of our lives; it is to cultivate a heart that can unconditionally welcome all things. We bow to what is, to all of life. By liberating our minds from ideas of “better than,” “worse than,” or “the same as,” we liberate ourselves from all views of “self”and “other.” The bow is a way to the end of suffering, to an awakened heart.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.