Even if it were not one of the most private things about us, belief would be among the hardest to communicate. What touches us deepest is what can be transmitted least. As Oscar Wilde once noted, “People whose desire is solely for self-realization never know where they are going. They can’t know.” And so anyone who has traveled to a belief-system different from that of those around her faces the most agonized, and poignant, of miscommunications, crying to those around her—as they cry back to her—“Why why why can’t you love (or trust, or understand) what I do?”

At the heart of Jane Campion’s powerfully involving and intelligent  new film, Holy Smoke, is precisely that unanswerable question: Ruth (Kate Winslet), a shining, spiky young woman from suburban Sydney, travels to India and almost instantly falls in (or in love) with a local guru. It’s all her addled parents back home can do to trick her into returning from Old Delhi and to summon a professional “cult exiter” from America, P.J. Waters (Harvey Keitel) to prise her out of her belief. Alone in an elemental desert, as golden and wasted as anything in Rajasthan, Ruth and P. J. circle one another in a “Half Way Hut,” she hanging onto her “love,” he determined to show it’s nothing but delusion.

new film, Holy Smoke, is precisely that unanswerable question: Ruth (Kate Winslet), a shining, spiky young woman from suburban Sydney, travels to India and almost instantly falls in (or in love) with a local guru. It’s all her addled parents back home can do to trick her into returning from Old Delhi and to summon a professional “cult exiter” from America, P.J. Waters (Harvey Keitel) to prise her out of her belief. Alone in an elemental desert, as golden and wasted as anything in Rajasthan, Ruth and P. J. circle one another in a “Half Way Hut,” she hanging onto her “love,” he determined to show it’s nothing but delusion.

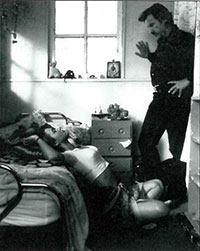

The struggle that ensues is intense and often harrowing, a kind of metaphysical dialogue with sexual sparks. The deprogrammer comes at Ruth with everything he’s got—using her language of “the soul,” the “spark” and “the path”—and she responds with the abandoned fervor of an angry, enraptured girl. He quotes Verdi to her, and Socrates, and the Gospel According to John; he even tells her of his own experience with a guru in India. When she resorts to quoting Baba (“It is. It is. It is.”), he is adept enough to tell her that the quotation comes from the Upanishads. Round and round they go the spiritual hired gun dressed all in black, the self-professed sannyasin in a white sari, playing tug-of-war with her soul, her very center. In this version of Jesus’s, or Buddha’s, days in the wilderness, the tempter to be resisted has just enough of the wounded Lawrentian animal in him to recall Keitel’s role as sexual healer in The Piano.

Anyone who knows Jane Campion’s films will know that her sympathies are fully and passionately with the way-out, unassimilated girl; all her films, from Sweetie to An Angel at My Table, to, most famously, The Piano, are essentially the same film, telling of a spirited and independent-minded young woman struggling to escape the limits of her red-brick home, and responding to some resonance that the provincial, stultified society around her can’t hear. And all her women risk becoming martyrs in their quest for liberation, as they are dragged forcibly back into the red dirt and shrunken hopes of home. The alien religion that Ruth embraces in Holy Smoke is really just another version of the artistry, the eccentricity, even the muteness that sets women apart in the other films, and that prompts society to wish to domesticate, or, in effect, to lobotomize and neuter them.

“I think you’re being manipulated,” says Ruth’s mother helplessly (and with a concern real enough to be affecting); her response, of course, is to try to manipulate her in a different direction, and to brainwash her out of what she sees as brainwashing. It doesn’t take long to realize that the “exit counselor,” with his military lingo, hoping to woo and maneuver and intimidate Ruth into submission, is merely a counter-guru with designs of his own, practicing what he might call a kind of psychic homeopathy (injecting her with snake venom in order to inoculate her against snake venom). In Campion’s vision, the truly sinister and smothering place, where the soul comes unraveled, is not Chandni Chowk but Sans Souci, Sydney.

What makes Holy Smoke much more compelling than this schema suggests is the simple fact that Campion uses the language of film so beautifully, evoking the flies, the shouts, the swarm of India and, especially, the moments of transport and interrogation, with a quivering, pointed immediacy. Every now and then Neil Diamond comes onto the soundtrack, singing “I Am . . . I Said” or “Holly Holy,” and one does not have to know that he is a perennial favorite in the subcontinent to appreciate how right the overblown operatic sincerity is for all of this. If there is a flaw in Campion’s often transfixing vision, it is that she is clearly more interested in what Ruth is fleeing than in what she is running towards; ultimately, her concern is not with faith so much as with the way it intensifies distances in a dysfunctional family. In that respect, she plays right into the hands of those who believe that people who practice foreign religions are acting more from weakness than from strength, and Ruth’s surrender to the guru, in the midst of a psychedelic rave, during her first few cinematic seconds in India, is as abrupt and unnerving as any parent’s fear: Baba zaps her in the Third Eye, and her other two eyes close.

Campion wants us to understand and cheer on rebellion—”The mind is a rebel. It is not a servant” is one of the cult exiter’s most pointed lines (even if it backfires against him). And Ruth’s attraction to her Baba makes sense principally as a reaction against the dopey, video-game absurdity of home. Australia, in this very broad portrayal of it, becomes a loony cartoon of wigs and “theme nights at the pub” and girls in leopard-skin bikinis (Sheila Bovaries) panting for sexual and emotional release. Everyone is a hypocrite of one kind or another, and amidst the trim lawns and identical houses of a suburban street, the superstitions are just as outlandish as anything in India. “What do you believe in?” one boy asks another. “Safe sex,” he smirks (writing off the Lord’s Prayer as food for “traumatized, paranoid worms”). In a desperate attempt to make contact with her lost daughter, Ruth’s mother—the only real person in the lot—assures her that she’s interested too in “the magnetic draw of the planets” and “the healing power of crystals.”

Clearly, the very people who are most violently fretting over Ruth’s loss of self are themselves in an even deeper kind of bondage (they puff on inhalers, run away with secretaries, yearn for moments outside their control); and as Holy Smoke intensifies, it expands the guru theme into a much larger discussion of power, and becomes, in effect, a two-handed treatise, fearless and raw, two-handed treatise on sexual politics. Once Ruth is broken down—purged, really, of her devotion—she begins to turn the tables on her tormentor, needling his male insecurities and fears, using her body to play with his mind, and turning him round till he’s naked, and crying, pathetically, “Man-hater!” The film becomes an explicit argument on what Campion might call “patriarchal oppression”—”I believe there’s another door through disintegration into euphoria and that maybe only a woman can get there,” says Ruth in the book of the movie—and as she deprograms the deprogrammer (entering the exiter), she is left shouting that at least in India they’re “honest in their hatred of women.”

By its end, the film has become a kind of New Age version of Mad Max, with Ruth clomping across the desert using copies of Dostoevksy for shoes, and P.J. following after in a dress. Yet what electrifies it throughout, and makes it much less abrasive and reductive than the book of the story (written by the Campions), is, simply, Winslet’s overpowering, completely uninhibited performance as a lost and luminous soul whirling through space in a blur of radiance and skittishness. Fresh (if that is the word) from playing Ophelia, and then another hippie waif dragging her children through the dust and alien couplings of Morocco (in Hideous Kinky), she summons a conviction so piercing and even unsettling that we never know where she will go next. It’s all the soul cowboy from America can do (fresh from his own performance in the somewhat less holy Brooklyn movie Smoke) to look up at her and mumble unctuously, “I don’t hate women; I love ladies.”

The Buddhists, I suspect, hearing of this nervy movie, might assume that it has nothing to do with them: Buddhism, after all, based traditionally in self-questioning and self-teaching, seems a world away from personality cults. Yet, in recent years with teachers from the East suddenly flying around the West in unprecedented numbers, and with people from everywhere more able than ever to seek out wisdom in Lhasa or Kyoto or Varanasi, there is unequivocally more scope than ever before for the kind of cross-cultural confusion that the Dalai Lama’s younger brother, himself an incarnate lama, calls the “Shangri-La syndrome.” Neither party really knows where the other is coming from, and both are suddenly propelled into the kinds of dialogue the film brings to life. Just two weeks ago, I went out to lunch in Nara, where I live, and met a young Japanese woman who had just escaped from a horrifying experience being taken in and assaulted by a Tibetan teacher in Delhi; and even in the Dalai Lama’s reception room, as I waited to see him in Dharamsala last month, I came upon an article describing a serious scandal in a Buddhist group in Malaysia. What the world calls “cult issues” are more and more a part of the Buddhist experience in every corner of the globe.

Campion’s film takes us into the complex heart of this transaction much more vividly than the guru novels of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, say, or the conventional movies (most recently Indien Nocturne) of a seeker following the scent of himself in India (let alone such films as Bengali Nights, featuring Hugh Grant as Mircea Eliade in Calcutta, confusing sacred and profane loves); the director and her sister actually enter the skin of one who’s made a leap of love, and bring no condescension or judgment to her (that, they reserve for the folks back home). Yet as I watched Holy Smoke, I couldn’t help but think of the passages towards the end of the Dalai Lama’s most recent major book in English, Ethics for the New Millennium, in which he says, as he does more and more often, and with uncharacteristic vehemence that, though all religions have much to teach us, and though a handful of souls really may belong in a different tradition from the one into which they were born, for most of us, the best way to cultivate restraint, virtue and compassion is “to remain firmly committed to our own faith,” where there is less danger of confused motives, less lure of exoticism, and less pressure in trying to adapt to a philosophy that’s risen up in response to circumstances very different from our own.

The cult exiter in Holy Smoke scores his strongest points when he asks Ruth what she actually learned from “Bubba” (as he pronounces it), to which she can only answer, rather abstractly, “To be a good person.” How has it made you a better person, he presses on, and she, echoing Wilde, perhaps, can say nothing. It is the man in black, in fact, who ends up scrawling “BE KIND” across her forehead, prompting her suddenly to abandon her mind-games and to recall the Dalai Lama’s wisdom. “That’s the whole point,” she says, as both characters finally move towards a course of compassion and social action. The sentence of the Dalai Lama’s she doesn’t quote, however, is the one in which he says, about changing faiths, “The danger is that the individual may, in seeking to justify their decision to others, criticize their previous faith. It is essential to avoid this.”

Holy Smoke, Miramax, 2000

Directed by Jane Campion

Written by Anna and Jane Campion

1 hr., 55 mins., Rated R

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.