Out of nowhere and interrupting an otherwise beautiful May morning, I just so happened to hit the jackpot of drama, the grand slam of misfortune, a condition I’d soon learn is sometimes spoken of in medical circles as “the worst possible thing.” I was slapped with three uppercase initials—ALS—that signified I was now victim to a rare, quickly debilitating neurological disease. It was the kind of disease which results in total paralysis—including the loss of one’s voice and an assured countdown to respiratory failure—within a few years for nearly all who are diagnosed with it.

Of course, I hadn’t seen any of it coming. The day before the diagnosis, I was so confident in the promising course of my future that increasing life satisfaction felt almost fated. In 2016, I was thirty-five and at a beautiful resting point, relaxing into a well-curated adulthood, seemingly removed from having to reckon with the threat of death. I was growing accustomed to feeling competent and in control.

Call it chance, or destiny, or the cunning cosmos wanting to poke a hole in my existential hubris, but reality had other plans for my precious life. I was being schooled in the ancient lesson that most of us will learn eventually: that certain blessings are safe to take for granted until the day they are suddenly, inexplicably, shockingly not.

The morning carried a warm spring breeze that seemed to herald a general cheeriness from everyone, chattering squirrels included. The route to my appointment with a neurologist had me weaving my bike along the Boulder Creek path around joggers, parents with strollers, and skateboarders. Wildflowers sprouted up along the edges of the pavement in obstinate declaration.

There was, though, one thing tugging at the corners of my attention in an increasingly troubling manner. It began the previous fall, when I noticed myself fumbling while dressing. Bra straps and buttons became progressively more difficult to navigate; it was as if my fingers had stopped cooperating with my direction. At first it just seemed weird and only faintly worrisome. Is it my imagination, or am I getting clumsy? Is this really a thing? But over the months these unexplained symptoms slowly progressed to include my wrist, making cooking, doing dishes, and typing a little more challenging.

After parking my bike and checking in at the front desk, I was promptly invited down the hall to the doctor. He asked me to sit. He looked pained.

Taking a deep breath, he said, “I’m afraid to tell you that I believe you have a condition of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.” My heart pounded. My stomach dropped. I stared, waiting for him to explain. “Are you familiar with it? It’s also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease.”

Something within became a little thick and fuzzy. It was as if a blanket suddenly wrapped around my brain, cushioning me from extra input. My tears came despite my wanting to hide them. “I’m sorry,” I said, knowing they might make him uncomfortable. He responded with a gentle “Of course,” as if he were surprised I was holding it together at all.

I asked if the illness shortens people’s lives. He nodded but said nothing more. Not really knowing what else to say but desperate for some hope, I asked, “Should I eat in some special way?” He shook his head and said it wouldn’t matter. At this point I realized he was no longer looking me in the eye.

I then managed to stumble down the hall and walked outside until I found a secluded spot along the creek. It was there, sitting in the damp grass under the dappled morning light, that I first learned everything about my new diagnosis the doctor had not been willing to tell me.

As I scrolled through the search results on my phone, I read that ALS has no known cause and no cure. Treatment is practically non-existent and really designed only for comfort. It’s a process of progressive, inevitable motor neuron death, often starting in a limb and then quickly spreading to devour one’s entire body. The mind is rarely affected. Late-stage patients would need a feeding tube and a breathing machine. Most live between two and five years after diagnosis. In that time, they become quadriplegic with no voice, eventually dying of suffocation once their lungs lose their strength. The death rate is 100%.

I called my husband, John, and broke the news to him. Stunned, he said he would cancel his clients and meet me in the park near his work. On my way over, I noted all the innocent people whose lives hadn’t just been pulled from under them. There they were, in their own everyday life dramas, jogging their dogs or rollerblading with their headphones or strolling with friends, lost in conversation: “Get this! And then Kerry said…!”; “I don’t know which job would be best…”; “… and then I’ll have to take a red-eye flight to…” I’d listen to these snatches of conversation, knowing these people were completely unaware of their incredibly good fortune. By all appearances they still had a future, or at least a convincing illusion of one. I simultaneously envied them, prayed for them, and pitied their lack of awareness of their own vulnerability. This mix of feelings would quickly become a familiar flavor.

When I met John, he threw down his bag to embrace me. After some moments together in silent trembling he choked out, “We’ll get through this together. We’ll get through this.”

I nodded and buried my wet face in his chest.

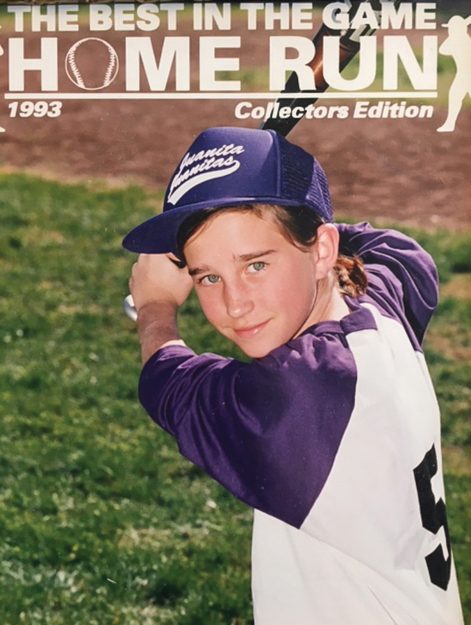

Throughout this week, I reflected on my lack of serious concern about my health up until the moment I was diagnosed, how I had so blindly assumed I wasn’t a real candidate for a deadly disease. After all, these types of things happened to unlucky people, older people, and, most importantly, other people. Maybe even people who were careless or sloppy about their health. If anyone ever had an “in” with the fates, I must, because I was so intentional about taking care of myself physically, emotionally, and spiritually. Right?

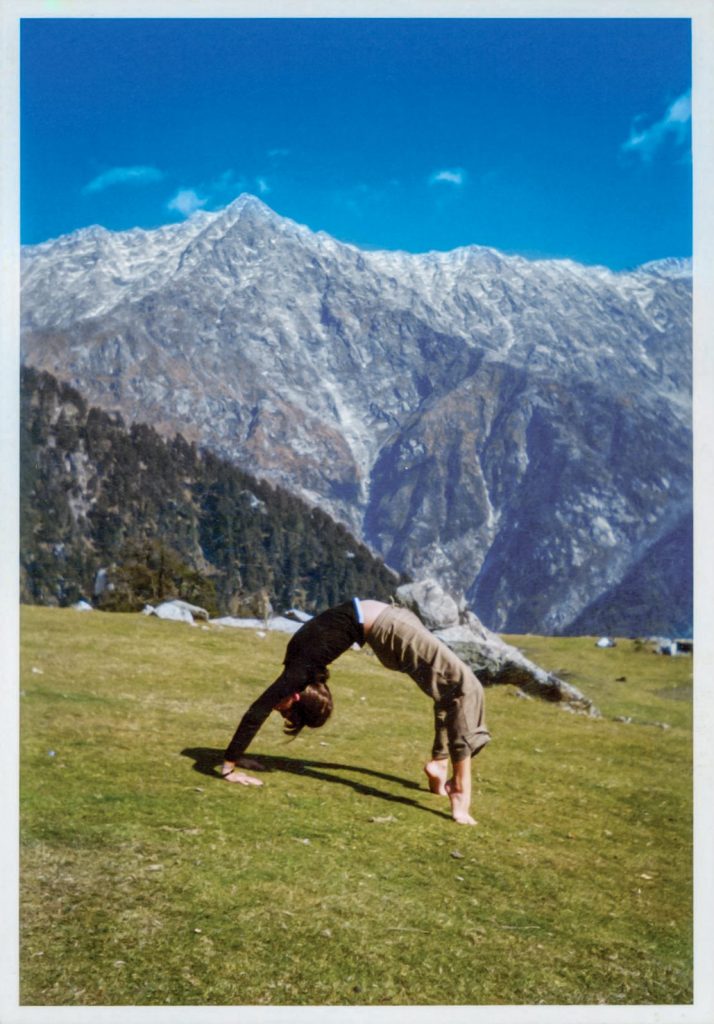

I exercised daily and went to yoga weekly. I smoked nothing and drank next to nothing. I hadn’t eaten fast food since I was a teenager. I’d been abstinent from sugar for almost a decade. I’d been advancing steadily through a series of meditation practices under the tutelage of a respected Buddhist teacher. I went to my own psychotherapy.

I wanted to be triumphant in my own hero’s journey; I wanted to manufacture a miracle.

In my mind, all this meant one thing: I was good, damnit. I was “good” at respecting the literal and energetic laws of well-being, so it seemed obvious that life should be good to me in return. This was me after all, the center of my own special universe, and I hadn’t seriously entertained the possibility of a major misfortune. Or, if a misfortune happened, I assumed it would be of the sort where I could get the treatment available to fix it, and the strength of my resolve and determination and wits and karma would carry me through.

This kind of magical thinking had managed to continue unexamined even though I knew from working with therapy clients from every walk of life that shit happens, to everyone, often at the worst possible times. And it persisted even though I had long studied the Buddhist teachings on the nature of impermanence, which say all things “good” and “bad” inevitably change and that “death comes swiftly and without warning.”

I had so many questions as I attempted to make sense out of the senseless. I wanted to know what had gone wrong in my life and body, and what to do about it; what my illness meant, what I needed to learn from it, and most importantly, how to heal. I wanted to be triumphant in my own hero’s journey; I wanted to manufacture a miracle. And I was prepared to use every ounce of will and wit I could muster to make it happen.

In the months before my diagnosis, I had been nearing the completion of ngöndro, a set of practices in the Vajrayana path of Tibetan Buddhism. Ngöndro entails many hundreds of hours of contemplative practices, including physical prostrations, mantras, and visualizations, all meant to build on each other to wear away the various egoic blind spots that shield us from the brilliant, interconnected, groundless nature of reality.

At least, that’s how ngöndro had been presented to me by my teacher. And, in many ways, the path delivered. I slowly softened, became less guarded, more present. I had been studying with this teacher and in this community for ten years. It felt like we were all doing something special, something sacred, and I wanted to be “all in.”

Although I had been a diligent student all along, I lacked confidence in the outcome of my efforts. I suspected I wasn’t really getting whatever insight I was supposed to be getting and likely needed to work ever harder to find the calm, luminous awareness that was supposedly already within me. I especially longed to experience those moments in meditation where the breathtaking beauty of reality reveals itself so powerfully that one can’t help but gasp in ecstasy. Despite my teacher’s reminders that these experiences were unnecessary and sometimes even distracting to a true understanding of the path, I wasn’t convinced. I’d sit in retreats during special teaching sessions, trying hard to will myself to relax enough to let go, and, little surprise, it didn’t work. Instead, I often felt completely, utterly ordinary, catching myself wondering when the practice session would end so I could go for a walk or make some toast.

“I’m just not getting it! I’m really… just, basic,” I would confess to my teacher and any other senior practitioners who would listen. They would all assure me I was, in fact, getting it, insofar as there was an “it” to “get.” Yet my spiritual imposter syndrome persisted, with me assuming I had fooled them all into vastly overestimating my meditative abilities.

Still, though I carried these insecurities and doubts as constant companions, I felt committed to the process and was planning to steamroll ahead. I devoted two or more hours most days to practice, and I knew some inner alchemy was taking place, even if it was painfully slow. So I figured, though I may forever be a remedial student, at least I was making some tidbit of progress, if through nothing other than my stubborn willingness just to sit down each day and follow instructions as best I could.

Days after the diagnosis, my teacher tried to support me by scheduling a meeting to help me modify my practice to the new situation. His suggestion to double my daily hours of meditation felt like a good idea until day two, when it started to feel like punishment more than support. Something in me knew that my belief in earnest striving had been irrevocably punctured. Pushing for realization now seemed useless. In some respects, I suspected my journey of waking up had only just begun.

Later that week, I lay next to John, grateful to have made it to the mattress. My second-opinion appointment had yet to arrive, affording me a sliver of hopeful comfort that this whole nightmare could soon dissolve. But this hope was buttressed by fear, what-ifs, and problem-solving fantasies, now a rapidly paced news scroll underlying every waking moment. This seesaw swinging between imagined grim or redemptive futures was crippling, rendering slumber my new best friend, a forgiving respite in the landslide of unknowns.

I pulled the covers up as far as I could. Perhaps I had taken a bath before bed, or perhaps I was simply exhausted; either way, I relaxed effortlessly, nursing the gradual surrender into sweet unconsciousness. But rather than drifting off to sleep, as I lay there semiconscious, I gradually became aware of a vivid, full-body experience of falling.

Down…

down…

down.

I fell for a good twenty seconds or so—down, down, down—enough time to observe that I was clenching all my muscles in fear, desperate to stop the wild powerlessness. It was as if I were physically arguing with gravity, hoping if I resisted strongly enough I could make it all stop and prevent the eventual violent smack against the hard earth.

Yet halfway into this fall, without conscious intention, something within just relaxed. My muscles slackened as I realized I could simply exhale with my whole body instead of holding my breath. I was still falling, but my fall became easy, just a floating sensation that happened to be quick and downward through space. My body surrendered to a gravitational process over which I had no control.

And then it stopped. I didn’t hit the ground—the whole falling sensation just evaporated as quickly as it had started, even if the relaxation itself felt timeless. Once again, I became just a person lying in bed, a bit stunned, trying to grapple with what had just happened. While it might have partly been a natural by-product of a nervous system on the fritz, I knew it wasn’t so mechanical. It felt unusually foreign and important, like something I would be wise to remember. It was as if something outside of me—or perhaps deep within me—had offered a teaching so my body could learn to relax into what I was facing with a certain grace.

From the beginning, I was determined to make a triumphant return from the underworld of terminal illness. Despite conventional medicine’s utter lack of interest in helping, I had been willing to try nearly everything and anything over the next three years of battle. I had tweaked my diet in dozens of ways. I did liver and gallbladder flushes, glugging olive oil and lemon juice before bed and hoping for a miracle in the morning. I tried dozens of protocols with various wonder supplements, each new combination promising to conquer what the last round had not.

There were energetic treatments such as Reiki and bio-resonance. There was acupuncture. There were bitter sludges of Chinese herbs. There was tapping, visualization, affirmations, shamanism, and endless meditation.

And I got so very tired. Physical exhaustion was a given, but it didn’t compare to the emotional and mental fatigue of investing all my hopes into failed treatment after failed treatment. All my best efforts had so far barely caused a ripple in my physiological deterioration. It became harder and harder to imagine that my body would respond to anything. I lost faith and enthusiasm. And I had no idea where to find it again.

Against this backdrop I began to admit there were no reasonable options left for pursuing recovery; that continuing to drag John along in my longshot efforts was unkind, bordering on absurd; that it was finally time to cease this mad searching, this fighting, this striving, and let go. These thoughts pierced through my mind with a hot, searing sting.

As I sat with this stubborn impulse over the following few days, something tangled inside began to unravel. I knew dropping the fight by this point would be no small change in orientation.

This was not the first time I had cried uncle. Overwhelmed with grief and frustration, I’d surrendered again and again to the emotional pain of the situation, which usually resulted in a long cry, allowing me just enough relief to plow forward with my determined project of changing my fate. But fully surrendering to the inevitability of my progressing disability had an altogether different feel. If working extremely hard for physical recovery yielded zero results, perhaps recovery wasn’t the right goal for me anymore. Not that I didn’t deserve it, but maybe I deserved the lessons that come from surrender and grace even more.

Maybe it was time to redefine what healing would be for me. And if I stopped fighting my physical reality, I could just relax into the freefall, much as that experience that came over me a few nights after diagnosis had taught me to do.

I made a decision. I would leave my fate up to something beyond my ego. My own tricks and tools would no longer be in the fight. With this decision, my psychic pressure valve started to hiss, allowing the many long months of struggle to slowly deflate.

Ending the fight with the illness in no way meant I was powerless. In fact, surrender meant that I could reclaim my locus of control. I now knew no guru could save me. No doctor could save me. No shaman, intuitive, or miracle worker could save me. My own best ideas had not saved me. And focusing on physical treatments, though understandable for a time, distracted me from having to grapple with everything that I still didn’t know how to fully grapple with: my pain, my fragility, my rage, my potential, my passion, my desire to belong on this fucking hard but beautiful planet, my desire to be and do enough and my fear that I never would. To mine whatever jewels I could from this situation, I’d have to turn within to my deepest questions, to heart questions. I’d have to wait in darkness and listen like I’d never listened before. My dear sweet self, what seems to be the root problem? Is there truly a problem at all? What will nurture my spirit, and what does my body need now? What do I most need to let go of, and what am I most hungry for? And most importantly, what is the true healing I seek?

I was now free to explore what of me might still be left glinting in the rubble of my former life, despite my paralysis and progressive decline, despite everything I’d already had to let go of. By late summer of 2019, I had settled into a simple routine, rarely leaving the house except for a doctor’s appointment or a drive through the foothills with John. Whereas my life had once been cluttered with work, exercise, errands, household projects, travel, social events, and generous planning for the future, my choices were now simple. I could nap; I could write; I could sit on the deck and watch the squirrels fight and the grasses sway; I could meditate or read great literature. I could reflect on my kooky and colorful dreams; I could get lost in albums I loved. I could slowly tap out a sparse conversation with a visitor, allowing for deep breaths from both of us. With eye-gaze technology that allowed me to operate my computer visually, I could connect to the internet. Even my surfing somehow felt more interior and spacious.

While artists or meditators sometimes go to great lengths to create situations of solitude, my body was essentially creating a solitary retreat for me, forcing me to slow down and beckoning me to listen. I realized if any illness is capable of encouraging introspection, I’d been awarded the most ingenious version. I could still question, learn from my mistakes, choose consciously to approach things differently. I could comfort, counsel, and advocate. I could appreciate myself and everything I’d survived. I could let my heart break further than I ever thought possible. I was still a wife, daughter, sister, friend, and ally who could reflect on everything unique and yet stunningly ordinary about my human life—my aching, imperfect, exquisite human life, which currently still existed.

Loss itself is not a gift; loss is just loss. Pain is not okay just because we can grow from it.

Throughout my life, I had hungered for what was next, as if the true satisfaction was held in the distance somewhere, dependent on the proper arranging of circumstances—the right home, the right work, the right love, the right skills—and on leaving behind the wrong emotions or habits or hurts. Yet in the process of waiting for my never-ending desires to be actualized and my neuroses to be neutralized, I often missed the goodness constantly chirping at my own feet, begging for attention and appreciation, begging to have me rest, look around, and say, “Ahh. For today, this is enough. My life is already enough.”

To my surprise and delight, I found that marching further into the disablement of my condition did not necessarily mean greater despair. I could relax in contentment instead. In fact, I could even discover some joy while living in suspended animation between worlds. Despite the doctors who called this the worst possible disease, despite the people who claimed they would rather die than experience my fate, my life still had value. It was still, to me, a life worth living.

Even if the promise of hidden blessings—of jewels to be mined in the rubble of misfortune—provides some comfort, the idea itself deserves care and nuance, and it is probably best left up to each survivor to decide how much—and when, if ever—it’s worth embracing.

Loss itself is not a gift; loss is just loss. Pain is not okay just because we can grow from it. We never need to be blown apart just because we can learn from the act of piecing ourselves back together. And being able to mine meaning does not necessarily make it all worth it. When something as precious as our own health or the health of someone we love is snatched away, we might not ever find the necessary spin to see a bright side; we might not ever identify a happy ending.

It seems the more permission we give ourselves and each other to have all the feelings and questions—without offering tidy answers to shunt the process—the more empowering it’ll feel to define our own meaning, in our own time, as best we care to. We may remember loss is as old as time, and we are born into vulnerable bodies, loved by and loving creatures also in vulnerable bodies.

But if heartbreak is a given, so is resilience. Sometimes just enduring itself is meaningful, affirming that we can keep going even when life has us in a headlock and our whole being whimpers in resistance. The more we can rest in our vast, broken-open heart without flinching—and the more we can cherish the body we have no matter how limp or exhausted or disfigured—the more equipped we are to inhabit with courage the life with which we’ve been entrusted.

Eventually we can gather together the lessons learned in survival and share them with others—even if it’s simply a quiet internal mercy for everyone who feels similarly broken. In this way we may weave our pain into a tapestry that warms others or protects them or simply keeps them company. In this way we allow something meaningful to arise, and in doing so we make the damn jewels.

And that, friends, may just be the real miracle.

♦

From No Pressure, No Diamonds: Mining for Gifts in Illness and Loss by Teri A. Dillion, Pomegranate Publishing. ©2020 by Teri A. Dillion.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.