During my own practice and teaching of meditation over the past thirty-five years, many things have surprised me, but none more than the growing and somewhat anguished realization that simply practicing meditation doesn’t necessarily yield results. Many of us, when we first encountered Buddhism, found its invitation to freedom and realization through meditation extraordinarily compelling. We jumped in with a lot of enthusiasm, rearranged life priorities around our meditation, and put much time and energy into the practice.

Some, engaging meditation in such a focused way, discover the kind of continually unfolding transformation they are looking for. But more often than not, that doesn’t happen. It is true that when we practice meditation on a daily basis, we often find a definite sense of relief and peace. Even over a period of a year or two we may feel that things are moving in a positive direction in terms of reducing our internal agitation and developing openness. All of this has its value.

But if we have been practicing for twenty or thirty years—or even just a few—it is not uncommon to find ourselves arriving in a quite different and far more troubling place. We may feel that somewhere along the line we have lost track of what we are doing and that things have somehow gotten bogged down. We may find that the same old habitual patterns continue to grip us. The same disquieting emotions, the same interpersonal blockages and basic life confusion, the same unfulfilled and agonizing spiritual longing that led us to meditation in the first place keeps arising. Was our original inspiration defective? Is there something wrong with the practices or the traditions we are following? Is there something wrong with us? Have we misapplied the instructions, or are we perhaps just not up to them?

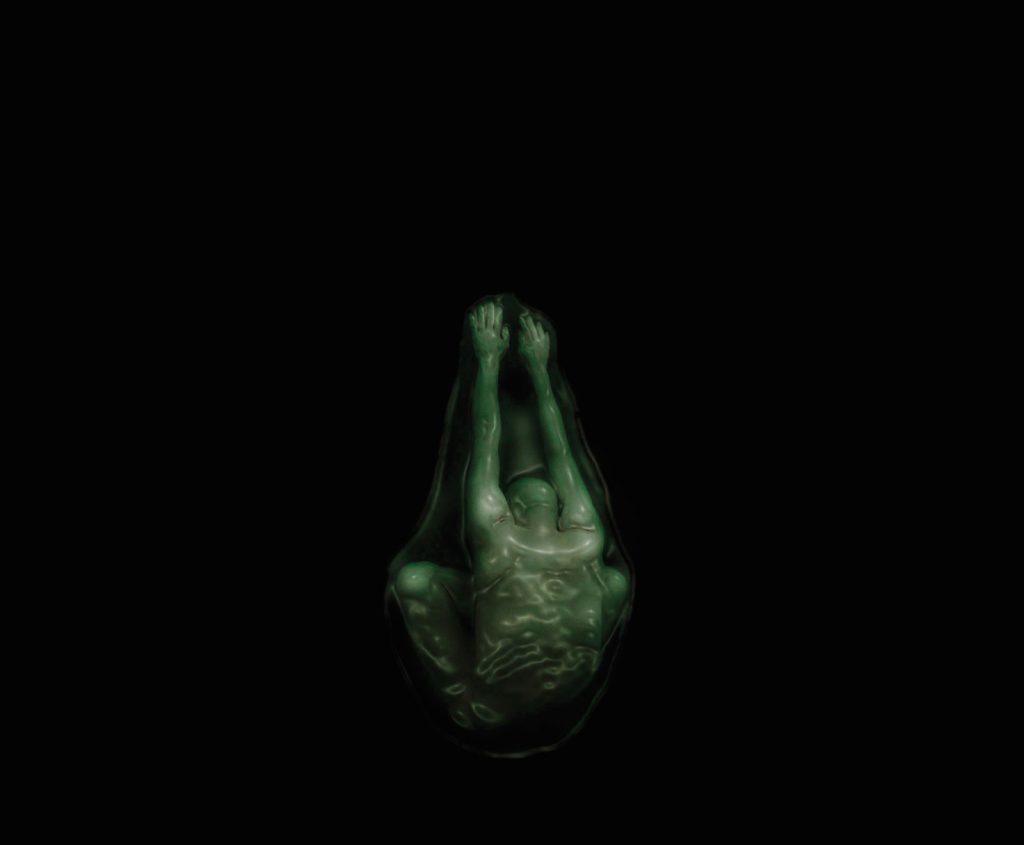

In an early Theravada meditation text, the phrase “touching enlightenment with the body” is used to describe the attainment of ultimate spiritual realization. It is interesting, if a bit puzzling, that we are invited not to see enlightenment, but to touch it—not with our thought or our mind, but with our body. What can this possibly mean? In what way can the body be thought to play such a central and fundamental role in the life of meditation? This question becomes all the more interesting and compelling in our contemporary context, when so many people are acutely feeling their own personal disembodiment and finding themselves strongly drawn to somatic practices and therapies of all kinds.

My sense is that there is a very real problem among Western Buddhist practitioners. We are attempting to practice meditation and to follow a spiritual path in a disembodied state, and our practice is therefore doomed to failure. The full benefits and fruition of meditation cannot be experienced or enjoyed when we are not grounded in our bodies. The phrase from the early text, when understood fully, implies not only that we are able to touch enlightenment with our bodies, but that we must do so—that in fact there is no other way to touch enlightenment except in and through our bodies.

For most of us, and for most of modern culture, the body is principally seen as the object of our ego agendas, the donkey for the efforts of our ambitions. The donkey is going to be thin, the donkey is going to be strong, the donkey is going to be a great yoga practitioner, the donkey is going to look and feel young, the donkey is going to work eighteen hours a day, the donkey is going to help me fulfill my needs, and so on. All that is necessary is the right technique. There is no sense that the body might actually be more intelligent than “me,” my precious self, my conscious ego.

For me, and for many people I know, there is a kind of divine intervention that arrives at our doorstep and calls us back to our body. This can take many forms: injury, illness, extreme fatigue, impending old age, sometimes emotions, feelings, anxiety, anguish, or dread that we don’t understand and can’t handle. But at a certain point we start to get pulled back into our body. One way or the other, something comes in, sometimes with a terrifying crash, and begins to wake us up.

When we operate in a disembodied state, we tend to understand the experiences of our life as random, relatively insignificant, and boring. We go to great lengths to try to find something interesting or significant in our life. The more boring and gray everything gets, the more we look to sex or violence or mind-altering substances or anything that can give us some kind of rush—anything to break through the phenomenal boredom and general meaninglessness of our existence. We may find ourselves thinking, “Next week I’m going to this great restaurant where maybe I can have a meal I actually enjoy,” or “Next month I’m going on vacation and maybe then I will be in a place that will actually catch my attention and mean something,” and so on.

According to the Yogachara teachings of Indian Buddhism, the problem with our life does not lie in the individual circumstances or occurrences of our day-to-day existence. It’s not that they’re inherently meaningless and boring. The problem is that we make them meaningless and boring; because we are so invested in maintaining our own sense of self, we actually don’t relate to anything in a direct way. Unwilling to fully live the life that is arriving in our bodies moment by moment, we find ourselves left with no real life at all. In our state of disembodied dissatisfaction we may think, “I feel like I’m disconnected. Maybe I need to change my job, or change my relationship, maybe, maybe, maybe.” But the fact is that the fullness of our human existence is already happening all the time. By drawing on Tibetan Yoga practices, which explore the body from within, we can learn to allow the experience of the body to communicate with our conscious mind and to become known to us in a direct way. As we begin to open up our awareness in this way, we can find intensity, meaning, fullness, and fulfillment in the most mundane details of our life.

The Buddha said, “I follow the ancient way.” He lived in northeast India at a time of increasing agriculturalization and urbanization with all of their attendant consequences. For his part, he left aside the compelling social changes around him and retired to the jungle—in Indian thought, the nonhuman locale where the primordial may be discovered. When the Buddha touched the earth as witness of his attainment, he separated himself decisively from the disembodiment increasingly sought by so many spiritual teachers and traditions of his own day, including his own previous meditation teachers and the dominant Hindu Samkhya-Yoga system. The Buddha made, I think, the journey back that I am suggesting here, and left as his legacy the full embodiment that Buddhist meditation, in its traditional context, represents.

In the classical Buddhist traditions, meditation is deeply somatic—it is fully grounded in sensations, sensory experience, feeling, emotions, and so on. Even thoughts are related to as somatic—as bursts of energy experienced in the body, rather than nonphysical phenomena that disconnect us from our bodies. In its most ancient Buddhist form, meditation is a technique for letting go of the objectifying tendency of thought and of entering deeply and fully into communion with our embodied experience. And hence it leads to “touching enlightenment with the body.”

And yet, among many of us modern people, meditation is often practiced as a kind of conceptual exercise, a mental gymnastic. We often approach it as a way to fulfill yet another agenda or project—that of attempting to become “spiritual,” according to whatever we happen to think that is. We may try to use meditation to become peaceful, sharper, more “open,” more effective in our lives, even more conceptually adroit. The problem with this is that we are attempting to be managers, to supersede nature, to control “the other.” In this case, the “other” is ourselves, our bodies, and our own experience. Ultimately, it is our own somatic experience of reality that we are trying to override in the attempt to fulfill our ego aim.

Often we have an ideal of what meditation is or should be—what we like about meditation, which might be some experience that we’ve had somewhere along the way—and we actually end up trying to use our meditation as a way to recreate that particular state of mind. We try to recreate the past instead of stepping out toward the future. To put the matter in bald terms, we end up using meditation as a method to perpetuate and increase our disembodiment from the call and the imperatives of our actual lives.

Unwilling to fully live the life that is arriving in our bodies moment by moment, we find ourselves left with no real life at all.

This is what the psychologist John Welwood calls spiritual bypassing. Meditation becomes a way to perpetuate self-conscious agendas and avoid impending, perhaps painful or fearful developmental tasks—always arising from the darkness of our bodies—that are nevertheless necessary for any significant spiritual growth. Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche called it spiritual materialism, using spiritual practice to reinforce existing, neurotic ego strategies for sealing ourselves off from our actual lives in the pursuit of survival, comfort, continuity, and security. When we use meditation in such a way, we aren’t really going anywhere, just perpetuating the problems we already have. No wonder when we practice like this over a period of decades, we can end up feeling that nothing fundamental is really happening: because it isn’t.

I am not certain that our Asian teachers, who come from very different cultural situations, always understand the full extent of our own disembodiment or the tremendous limitations it imposes on our ability to meditate and pursue the path. Nor do the classical Buddhist texts, at least as we understand them, necessarily provide a direct and effective remedy to our situation either.

Consider, for example, the meditation technique that is so central in the texts and so often given to modern meditators: pay attention to the breath at the tip of the nose, either feeling the in-breath and the out-breath or attending to the breath there in some other way. For a fully embodied person, this is an effective technique by which the practitioner can make his or her journey. But for someone who is somatically disconnected and habitually abides almost entirely in his or her head, using a technique that requires attention on the nose will reinforce the tendency to remain entirely invested in the head and to continue to be unaware of the rest of the body. If we are already out of touch with our body, its sensations, and its life, carrying out a practice that involves attending to the breath at the nostrils often just perpetuates and even reinforces our disconnection. Those of us meditating in such a disembodied state are locked into a cycle and genuinely trapped in our practice.

When the body calls us back, we begin to find that we have a partner on the spiritual path that we didn’t know about—the body itself. In our meditation and in our surrounding lives, the body becomes a teacher, one that does not communicate in words but tends to speak out of the shadows. Moreover, rather than being able to require the body to adapt to our conscious ideas and intentions, we find that we have to begin to learn the language that the body naturally speaks. As we come under the tutelage of the body, we often think we know what is going on, only to discover, over and over, that we have completely missed the point. And then, just when we think we are completely confused, we come to see that we have understood something much more profound and far-reaching than anything we could have imagined. It is all very puzzling but, in meditating with the body as our guide, we come to feel that, perhaps for the first time in our lives, we are in the presence of a being, our own body, that is wise, loving, flawlessly reliable, and, strange to say, worthy of our deepest devotion.

In entering into this process of developing somatic awareness, we are not simply making peace with our physical existence. In fact, we are entering into a process that lies right at the heart of the spiritual life itself, something the Buddha saw a very long time ago. He saw that while spiritual strategies of disembodiment may yield apparent short-term gains, in the long run they land us right back in the mess we began with, perhaps more deeply than before.

In meditating with the body, the awareness itself is being retrained and reeducated. We begin to live our life as a continual welling up from the depths of our soma, of our pores, our tissues, and our cells. Rather than thinking that the conscious mind is or should be the engineer of our lives, we begin to realize that the conscious mind is actually more appropriately the handmaiden of the body. The body becomes the continual source of what we need in order to live, the unending fount of the water of life. A very interesting teaching in the Yogachara tradition states that it is part of the human situation to try to maintain a certain self-image or self-representation, what Buddhists today refer to as the “the self,” the “I” or ego. The attempt to maintain the “integrity” of this continuous, solid sense of ourselves leads us to be very resistant to—in fact, to ignore—information that is inconsistent with that image. And this means that we have a huge amount of information, moment by moment, to block out.

According to the Yogachara, as we live our lives, the body itself is a completely nonjudgmental receiver of experience. These days there is much talk about creating effective personal boundaries. But the interesting point is that you actually can’t put up boundaries around your body. The boundaries happen up top, in the head. The body is open, the body is sensitive, the body is vulnerable, the body is intelligent, and the body is completely beyond judgment. From the body’s viewpoint, whether we like or dislike what is occurring in the world is irrelevant. Whatever occurs in our environment, our body receives.

While the body receives experience in a completely open and nonjudgmental way, because of our investment in who we think we are and our efforts to maintain this self, we refuse to receive a great part of what the body knows and feels and understands, “we” meaning our conscious self, our conscious mind, our ego. An experience occurs on a somatic level, and we say “no,” or we say, “I want this part of what happened but not that part,” but we don’t simply accept what the body knows in a straightforward way. This is what Buddhism calls ignorance. Ignorance is not being unintelligent, uninformed, or deluded. Ignorance is actually incredibly intelligent. Ignorance means that we block out the wisdom and knowledge already abiding in our body that is inconsistent with who we think we are or are striving to be.

This leads to another most important question: what happens to all that denied and rejected experience that we are already holding in our bodies? Simply put, all that somatic awareness and experience is walled off from our consciousness. It abides in a no-man’s land in our tissues, our muscles, our ligaments and tendons, our blood, our bones. The literally organic journey our somatic experience is making toward consciousness is aborted, and it gets jammed back into itself. And there it stays, in a kind of unhealthy stagnation where, in some instances, it may be unlocked by a body worker years or even decades later as a release of “trauma.” But as with our “traumas,” so with virtually every moment of our lives, the full range of our experience is not admitted, but is pushed back and walled off where it abides hidden in the body.

This rejection of the fullness of our experience is what Buddhism means by the creation of karma. The residue of experience that has not been lived through is, in Buddhist terms, the karma of result, wherein previously created karma results in limitations on our present awareness. In other words, the experience that is pushed back and walled off into the body is not in the least inactive. It continues to function as that which our conscious standpoint, in order to maintain itself, must continually strive to ignore. It is much like moving around a party, trying to avoid a particular person. All of your moves, while seemingly free and consistent with the wants and desires of your “party objectives,” are actually largely defined by trying to prevent any encounter with the unwanted guest.

We could speak of the rejected experience, the somatic knowledge that we wall off, as our unlived life. It is that part of our human existence, and often a very large part, that we do not feel, engage, accommodate, or incorporate. It is something that has come to our body, for whatever reason, but that we have allowed to go no further. Many of us feel that life is passing us by, that we are missing what our life could be. We don’t know why we feel that way or what to do about it. When viewed from the point of view of the body, however, this unlived life is precisely the life that is already ours, but that we are avoiding out of our desire to maintain our ego status quo. Of course we long for this life, and of course our sense of missing it can be excruciating. Meditating with the body provides a way for us to reconnect with our unlived life and, gradually and over time, to learn how to live in a more complete and satisfying way.

There is no other way to touch enlightenment except in and through our bodies.

What is involved in meditating in an embodied way and inhabiting the body in our practice? Initially we are talking about really paying attention to the body in a direct and nonconceptual way. This involves very focused work and work that requires regularity and long-term commitment. In fact, I would say that once one “catches on” to what meditating with the body is all about, one enters a path that will unfold as long as there is life. At the same time, the experiential impact of the work is immediately felt, so there is confirmation of the rightness of what we are doing and a natural trust in the process that is beginning to unfold.

Meditating with the body involves learning, through a variety of practices, how to reside fully within our bodies. What we are doing is not quite learning a technique and we are not quite learning how to “do” something—rather we are readjusting the focal length and domain of our consciousness. Thus we gradually arrive at an awareness that is actually in our bodies rather than in our heads. It’s not something you actually learn to do, it’s a way of learning how to be differently.

In the teachings of Tibetan yoga, it is suggested that we can use our breathing to move the situation forward. Tibetan yoga speaks about the outer breath, our normal respiration, and also about the inner breath, our life force or prana. The outer breath holds the inner breath, as a sheath of a plant holds its pith. When we bring our attention to the outer breath, we gain access to our inner breath, our prana. Whatever location in the body we direct our attention to, there the prana will go.

According to Tibetan teaching, we can quickly and strongly bring our prana to a certain location in our body by visualizing that we are breathing into it. We might do this by visualizing that we are bringing the breath into our body from the outside, through the skin, for example; or, we might visualize that we are just breathing directly into a location, such as the interior of the lower belly. Now here is the key point: wherever our attention goes, the prana goes, and the prana carries awareness right to that point. By directing the prana, we are able to bring awareness to any location within our body.

At first, for example, we put our awareness into our abdomen or into our heart center or into our limbs, into our feet, into our fingers, or toes. Although initially it does feel as if we are putting our awareness into those places, as time goes on we begin to sense that what is really happening is that those places themselves are already aware and we are tuning into the awareness that already exists, not just in these particular places, but throughout the entire body. We begin to develop more subtlety, and we gradually become aware of our tendons and ligaments, tiny muscles in out-of-the-way places, our organs, our bones, our circulatory system, our heart, and so on. Through that practice there slowly comes about a kind of shift in emphasis, a shift in the way we are aware as people. Habitually, there predominates in us a “daylight consciousness,” which most people experience in their heads as a kind of being up front and toward what we want consciously or intend for our lives. This kind of consciousness is really a way of being very focused on what we think, of bringing into awareness things that are in some way important to the project of “me.”

But when we are asked to place our awareness in our bodies, something different begins to happen. Often, when we begin to do this kind of interior work, we can’t feel anything at all. Some of us may feel like we don’t even have a body. But through the practices, we begin to be able to see in the dark, so to speak. We begin to become aware that a larger world is beginning to unfold at the boundaries of awareness. The only thing you see in the daylight is what you want to see; when you turn the lights off in the night, you see what wants to be seen, which is a whole different story. It’s not something we can focus on with our usual self-serving consciousness, but nevertheless, this information begins to come to us in a very subtle way. We discover that the body actually wants to be seen in certain ways. This is a rather surprising discovery for many of us. We can’t imagine the idea that the body might be a living force, a source of intelligence, wisdom, even something we might experience as possessing intention. We cannot conceive of the body as a subject.

We may begin with absence of feeling or numbness, but as we continue breathing, the places where we are breathing may begin to show signs of life, and we may become aware of some faint sensation. As we continue breathing into the various locations in our body, we are likely to discover blockages and discomfort. People often uncover vivid pains and discomfort they were only subliminally aware of or perhaps were completely unaware of. They may realize that they feel like throwing up all the time. They may sense they are very, very tight or hard in their lower belly or their throat or their joints. They come to see that nothing is really flowing and that there are certain places where they are completely shut down. While some places feel very hard and armored, others feel incredibly vulnerable, unprotected, shaky, and weak. One side feels shorter or smaller than the other. One side feels alive, the other dead. Everything is out of kilter, and we are filled with distress of all kinds. We want to scream or run, or jump out of our bodies. This initial step involves getting to know a body that is in a lot of discomfort, holding a lot of claustrophobia and a lot of pain. As our awareness develops, we begin to realize that our habitual—if subliminal—response to our somatic distress is an unconscious or barely conscious pattern of freezing: we are holding on for dear life, fearful and paranoid, tensing our body and our self so we won’t have to feel.

At this point, the practitioner is instructed to receive the information of uncomfortable or even painful tension into his or her awareness without comment, judgment, or reaction. When we do so, we begin to notice that a certain area of tension is coming forward, as it were, presenting itself with special insistence to us. It clearly wants to be known, above all other potential areas. In addition, it comes with a very specific calling card, a particular portrait of feeling and energy. More than this, the area of tension comes as an invitation—it calls for release. Now at first, we might find this call painful and frustrating because we don’t see how we can heed the call and act upon it. After all, it is the body’s tension, right?

But the invitation for release, to be discerned in the very tension itself, also brings critical information with it: it is actually us, our own conscious, intentional, focal awareness, that is responsible for the tension in the first place. It is our own overlay, so to speak, that is creating this feeling of freezing. As this becomes clear, we begin to discover that we have the capability to take responsibility for the tension, to enter into the soma, to feel how it is actually us that is holding on. At this point, we can, indeed, release. We have to let go of ourselves, we have to feel that the unpleasant tension is our own paranoid holding on, and we have to open, relax, surrender, and let go. This represents a leap into the unknown.

As we move through the process of discovery, it may begin to dawn on us that the body itself has an agenda that it wants us to follow. The agenda begins with some region or part of the body coming forward to meet our awareness, presenting itself with a certain energy, texture, and demeanor, alerting us to our holding, and then inviting us into the process of release and relaxation. The interesting thing here is that we are dealing with something that is not us, it is not the conscious mind, it’s not like “Okay, I have a back problem, I’m going to use this bodywork to solve my back problem.” That’s imposing our agenda on the body. The body is going to say, “Nope. We are going to start with the arches of the feet. This is where we are going to start.” And then the next day it’s the calves, the next day it’s the neck, and then the next day or the next month it’s under the shoulder blades, under the clavicles, within the interior of the chest. In other words, the body itself actually gives us the routine. It gives us the protocols and it gives us the journey.

In this work, we are called to let go of what we think we want or think we need, and listen deeply; we are invited to surrender to the invitations that come forward from the body to become aware and to open, relax, and let go. Through that process there is a gradual shift from feeling that the body is an object or a tool of our ego, to realizing that the body is the source of something that constantly calls to us with a primal voice that commands our attention and engages us in a process that we find extraordinarily compelling, even though we cannot fully understand what is going on.

When people do this bodywork thoroughly and deeply, whatever personal issues they may have turn up somatically. They appear in a way that is according to the timetable of the body, not of our ego-consciousness. It is amazing how literal it can be. People who have difficulty with self-expression may feel at a certain point that they are being strangled because they sense the energy collecting at the throat and are unable to move. People who are unaware of their emotions may experience their heart as if in a vice. Such extraordinarily literal somatic experiences can be very painful and difficult. It is clear why people numb themselves because basically, who wants to feel that? But when we understand that these sorts of discoveries are part of regaining balance, energy, healing, and a more wholesome relationship to ourselves, it’s a whole different story. We begin to have confidence in the pain that we run into, and the blockages, because we have tools that we feel have some hope of leading us through. In each new experience, we bring awareness to our bodies, feel the blockage, find the invitation to release, surrender our hold, and experience the relaxation, sense of unknowing, and open space that result when we do.

In this process, we become acquainted with our body in ever new ways. As we continue, we may feel almost as if each particular part of our body is opening like a flower. We find a sense of vitality and life and energy in each part of our body. We begin to realize that each part likewise has its own very specific and unique awareness-profile, if you will, its own personality, its own living truth. It has its own reason for being, its own relation to the “us” of our conscious awareness, and its own things to communicate in an ongoing way. With each part of the body there is a similar whole world that opens up and is available for discovery when we begin working with it. With each new discovery, who “we” are grows deeper, more subtle, more connected, and more open and extended. All of this unfolds from that first experience of numbness.

When asked “How do you exhaust karma?” Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche simply said, “When things come up in your life, you feel them completely and fully and you don’t hold back. You live them right through until they have completed themselves.” This applies to whatever is arising for us, not just what is painful, but what is pleasurable as well. When we are blissful and happy, we go along to a certain point but then pull back because we are afraid—perhaps it is too much and we feel we are losing our sense of self, or perhaps we are afraid it will slip away. This is because true bliss and true happiness, perhaps even more so than pain, are a negation of the human ego.

In the Yogachara teachings, within the “storehouse consciousness”—what we call the unconscious—are all the memories, all the experiences that we have not fully lived through. This understanding works well with modern psychological thinking. The process of the path to enlightenment, which can be demonstrated from the very earliest texts onward, is allowing the unconscious contents of our life to arrive in our awareness and to allow awareness to integrate what we find about ourselves and about the world. According to Buddhism, the unconscious is the body. Through working with the body in the way that I am describing, we actually are able to unlock and unleash all of these experiences and all of these things that have been insufficiently experienced and are therefore held throughout the body.

That’s why it is said in the Tibetan Yoga traditions that the body actually holds our own enlightenment. Until we are willing to live through some of the wealth of information and emotions that have been offered to us but rejected, our awareness remains tied up and restricted. The way they put it in the tradition is that the experience of working with the body unlocks memories and images and emotions that become fuel. This fuel creates a fire in us, a fire of all the vivid and intense pain held by these previously rejected aspects of experience. That pain is a fire that gradually burns up the structure of our ego—it is a visceral inferno. It is said that this inferno purifies awareness and makes the field of awareness very, very bright. The more we do the work, the more our awareness actually opens up. According to the early tradition, enlightenment itself is when the fuel is all used up. Awareness, no longer tied up in evasionary tactics, is set free and liberated to its full extent.

Through the work, we begin to discover some fundamental shifts in the way we are. There is a rich interior life of the body that we feel and experience, but which also somehow remains shrouded in mystery. At a certain point, we realize that we can’t tell whether something is physical or energetic, whether it is emotion or sensation, and we realize that we don’t need to figure it out. It begins to unfold. The so-called self, that relatively consistent type of person we have always been trying to be, becomes much less important, and there’s a willingness on the part of the meditator, or the body contemplator, to allow the self, the conscious sense of self, to die and be reborn, over and over.

Digging Deep

The first step in regaining our embodiment as meditators is to establish a clear, open, and intimate connection with our larger, macrocosmic “body,” the earth itself. In this practice, we will explore how the body can be felt as an incarnation of the earth. Earth breathing enables us to deepen our connection with the earth and to explore our identity with the earth itself. This practice also enables us to feel the support the earth offers us. The more we allow ourselves to feel supported by the earth, the more we are able to identify with the earth, the more room we allow ourselves for the inner journey.

The first step in regaining our embodiment as meditators is to establish a clear, open, and intimate connection with our larger, macrocosmic “body,” the earth itself. In this practice, we will explore how the body can be felt as an incarnation of the earth. Earth breathing enables us to deepen our connection with the earth and to explore our identity with the earth itself. This practice also enables us to feel the support the earth offers us. The more we allow ourselves to feel supported by the earth, the more we are able to identify with the earth, the more room we allow ourselves for the inner journey.

Take a good meditation posture and feel the earth under you. Even if you are on a cushion in a room on the sixth floor of a building, you are still supported by the earth. You may initially want to keep your eyes closed. Begin breathing into the perineum, the region between the genital area and the anus. Bring your breath into the bottom of your pelvis at the perineum. Feel any tension you may have in the perineum. Breathe in through your sitz bones. Let the bottom of your pelvis sink into the earth. Breathe into the area of your anal region and your genitals. With each out-breath, let your pelvis sink more and more deeply into the earth, so that you are sitting completely and without any reservation on the earth. Bring the energy of the breath up into the hollow of the lower belly.

Now begin to breathe into a point that is a few inches below your perineum, putting you in direct contact with the earth. We are extending our awareness beneath our body, into the earth. Bring the energy of the earth up into your body. Now reach a few inches lower and then a foot lower. You are literally reaching with your awareness down into the earth and breathing up through your bottom.

With each breath, let your awareness drop down a little further into the earth. Breathe in the inner breath, the inner energy of the earth. Sink lower and lower into the darkness of the earth, breathing the energy up. On the in-breath, you are bringing the energy up, and on the out-breath, you are dropping further down. As you breathe in, allow your attention to remain deep inside the earth.

Continue in this way, letting your mind sink down into the darkness of the earth with each out-breath. Allow yourself to come right to the point where you feel you are about to go to sleep, but stay present, and take the attitude that you are sinking into a mysterious realm where all the answers you have ever sought are waiting. Try to be awake yet hovering on the boundary of sleep. On each out-breath let yourself sink a bit deeper, and take note of whatever images arise. Try to sense the extraordinary stillness and peace of the earth.

After about ten minutes, let your awareness drop more precipitously, further into the earth: one hundred feet, two hundred feet, a mile. See how far you can reach. Continue to breathe the earth’s energy up into your lower belly, going further down each time. Then let the bottom drop out and let your awareness go in a downward freefall. As your awareness descends, gradually have the sense that the energy is filling your body: into your belly, your mid-chest, your upper chest, and your head. Keep reaching down, deeper and deeper. Continue reaching further and further, while continuing to let the energy further up into your body. We are now receiving the awakened energy of the earth in our entire body.

To conclude this practice session, transition by dropping all techniques. Simply sit in your body, feeling your body as a mountain, still and immovable, and notice the awake and present quality of your mind.

♦

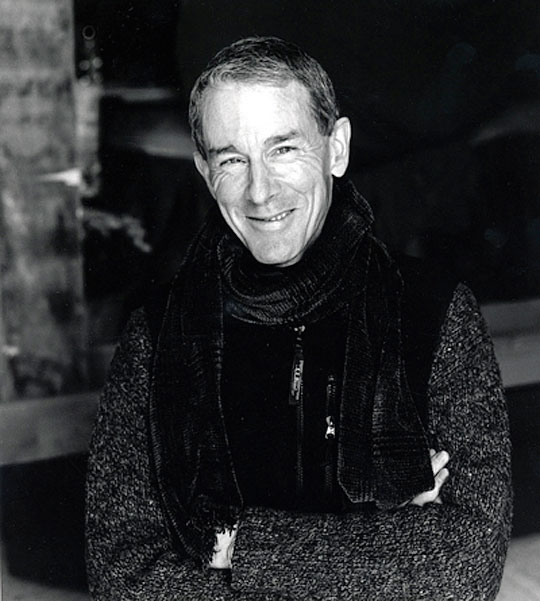

To explore somatic meditation further, watch Reggie Ray’s four-part Dharma Talk on Touching Enlightenment or his article Tapping into the Body for Radical Change and Transformation.

To listen to an audio-guided earth breathing meditation led by Reggie Ray, visit DharmaOcean.org.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.