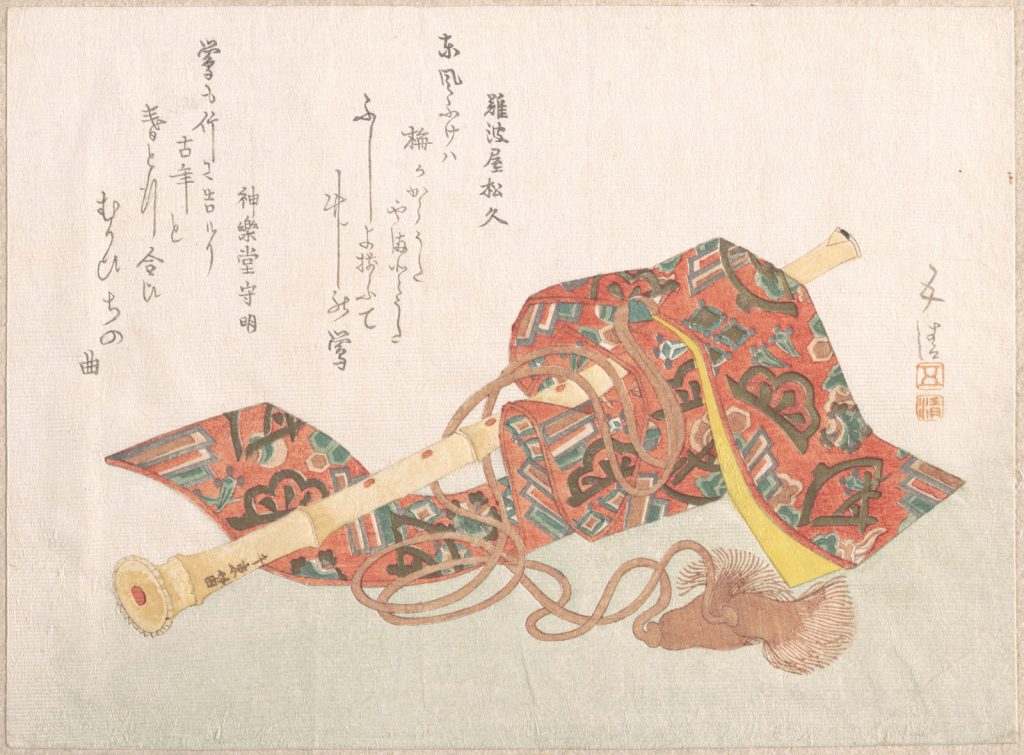

In music, tone is everything. A friend of mine studies shakuhachi, the Japanese flute. His teacher focuses almost exclusively on tone, for when the tone is true, the music is alive. Technical brilliance by itself may be impressive, but if the tone isn’t true, the music does not resonate, and those who listen soon become bored or restless.

The same holds true for meditation. There is a quality in attention, and when you hit it, your practice is alive and awake, and thinking and dullness drop away on their own.

As in musical training, it is often helpful to practice simple basic exercises to develop stability, clarity, and flexibility. One that I have found helpful is the one-breath meditation. This is good to do any time, but it is particularly helpful when you are feeling very agitated or very dull.

Related: Working and Playing with the Breath, a Dharma Talk by Thanissaro Bhikkhu

Don’t try to hold your attention on the breath. In the case of agitation, you will inevitably end up suppressing material, and you will become more agitated. In the case of dullness, you’ll keep falling into deeper and deeper torpor or even sleep.

Instead, breathe out just once. You are always able to have clear stable attention for one breath, so breathe out, gently and steadily without strain. At the natural end of the exhalation, stop. Let your body breathe however it wants to. Look around for a moment or two. If you wish, adjust your posture and move your body a little. And then breathe out again.

Just one breath. And stop. Do this over and over again.

After a few such one-breath meditations, you may find that a certain quality has developed in your attention, a stable clarity. It may be subtle. It may be fragile. But it’s there. You can’t make it happen. You can’t hold onto it. But it comes when you breathe out.

When you can touch that stable clarity consistently, do a two-breath meditation. Breathe out, breathe in, and then breathe out again. Then stop, look around, relax, move a little if you wish, as before. If that clarity was present throughout the two-breath meditation, good. Do it again. If not, continue with one-breath meditations.

When you feel ready, you can lengthen to three-breath meditations, or more.

You may think the point here is to build up your ability to rest in that awareness for longer and longer periods. You can take that approach if you want, but in doing so, you run the risk of falling back into a pattern of achievement, and that will cause problems down the line.

Practically speaking, on any given day, you will probably reach a point where that stable clarity no longer arises. Okay, you’ve run out of juice. That’s a good time to move to another practice or end your meditation period. No point in beating a dead horse, as they say. When you return to practice the next day, you will naturally pick up where you left off, fresh and rested.

In my experience, the important point is that you actually taste that clarity, just as the musician tastes what it’s like to blow a clear clean note that is true and awake. There is a body experience and a body memory in that single note practice, and the same holds true in meditation. When you hit that stable clear attention, mind and body both relax and are in tune, so to speak. And the more you touch into it, the more your mind and body become attuned to it. In this way, one-breath meditations can be more helpful than long periods of motionless sitting.

This article originally appeared, in slightly different form, in the Unfettered Mind newsletter. It was originally published on Tricycle’s website on March 5, 2019.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.