Lama Rod Owens has long been fascinated by the relationship between social liberation and ultimate freedom. As an author, activist, and authorized lama in the Karma Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism, he has worked at the intersection of social change, identity, and spiritual practice, exploring how activist work and spiritual practice can support each other. Recently, he’s been grappling with the question of what freedom looks like in our current political context and how spiritual practice can support us through our current crises.

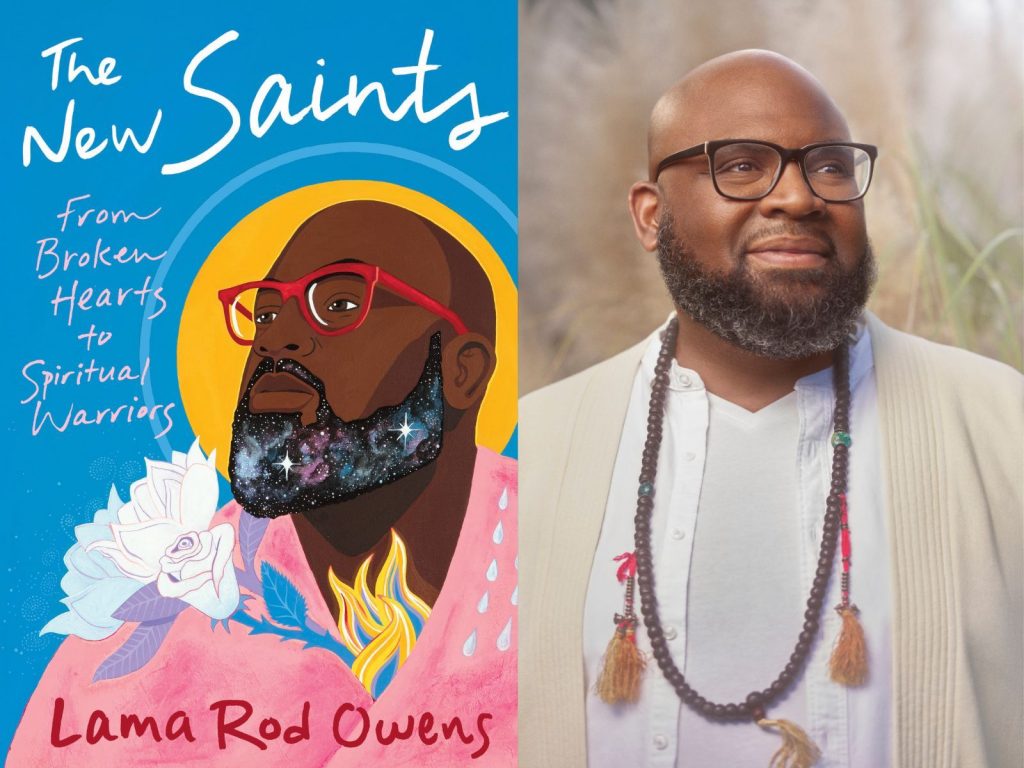

In his new book, The New Saints: From Broken Hearts to Spiritual Warriors, Owens draws from the traditions of Tibetan Buddhism and Black liberation movements to put forth the notion of the New Saint. “The New Saint is a rethinking of what it means to be a bodhisattva right now, with a particular focus on relative justice and its relationship to ultimate liberation,” he told Tricycle’s editor-in-chief, James Shaheen. “It’s about the contemporary experience of people in a world that seems to be on the edge of catastrophe.”

Shaheen sat down with Owens on a recent episode of Tricycle Talks to discuss why he believes that the apocalypse is an opportunity for awakening, the power of connecting with our ancestors and unseen beings, why the New Saint is not necessarily a good person, and how fierceness can be a form of awakened care. Read an excerpt from their conversation, then listen to the full episode.

You refer to the New Saint’s magic, which depends on two practices: the expression of awakened care and the development of our capacity to disrupt habitual reactivity. Can you walk us through what you mean by awakened care? Awakened care is my experience of bodhicitta. We traditionally define bodhicitta as the awakened heart-mind, but I would say that it’s the magic of the bodhisattva. It’s this view of deep connectedness and deep empathy, where we’re doing the work of liberation not just for ourselves but for all beings. When I am attempting to get free, that labor is also helping others to get free.

Not only do I have to choose freedom, I have to understand that I deserve to be free.

When I began to think about this in terms of the New Saint, I began asking myself, What is my actual felt experience of bodhicitta? The first thing I felt was love, this deep acceptance, holding space for everything and wishing for everyone and everything to be free. I also experienced compassion, tuning into the suffering of both ourselves and the world and actually committing to freeing ourselves and others from suffering. The other piece of this is joy. I feel deep joy for having the capacity to choose to benefit beings through my practice. I’m overwhelmed by that, and there’s deep gratitude in that joy as well. And of course, everything is based in emptiness, so we have the capacity for all of this to happen because of the profound potential of emptiness and space.

When all of this is streamed together, it begins to awaken care, a deep, profound care, the kind of care that says, “I’m going to do everything that I can to get free because I care that much for myself and for others.” An important point here too is that I have to care for myself enough to want to get free to begin with. And a lot of us aren’t there either. Some of us don’t really believe that we deserve to be free from suffering. Not only do I have to choose freedom, I have to understand that I deserve to be free.

You write that awakened care can cause us to lose a sense of agency so that we’re swept up in the agenda of the liberation of all beings and things. So how is it that we surrender to the agenda of liberation? [The author and filmmaker] Toni Cade Bambara has this notion of wanting to make revolution irresistible so that it’s the sweetest, most important thing that we could be doing, and it just becomes what we do and who we are. In awakened care, I’m trying to dissolve the sense of self, and that’s going to bring me into a more direct relationship with the essence or with emptiness itself. In a way, we can describe it as the cultivation of virtue.

When we practice goodness, it becomes a habit, where we’re choosing how to reduce harm moment to moment. We’re just attuned to choosing what will reduce harm. For me, that’s another way that we get swept up: we’re reprogramming ourselves to choose what is conducive to liberation. I want to get lost in that so that everything I do becomes an expression of goodness and therefore an expression of virtue.

One stream of awakened care is love, which you describe as a form of radical acceptance. Can you say more about how you’ve come to understand love? It’s hard to change when you haven’t really told the truth about what’s actually happening, and so the first expression of love is actually allowing ourselves to hold space for everything that’s arising. This is how it is. I don’t have to like it; I just have to name it and notice it.

I think what keeps us from doing that profound radical work of love is heartbreak. When I start telling the truth about how things really are, then my heart is going to break because I have been so concerned with telling myself narratives about how I want things to be in order to feel good about what’s happening. When I let go of that and say, “This is it. This is what’s happening,” my heart breaks, which is the experience of having to touch into this deep disappointment.

Once I start doing that, then there’s an honesty that awakens, and that profound holding becomes love. This is what’s happening, and therefore, I can make a choice to change what needs to change now because I’m not lost in these delusions and narratives about how I think things are; I know how things are. It creates a deeper intimacy with all phenomena and all beings, because you’re with the truth now, and you know that the truth is that everything and everyone deserves to be free.

Another aspect of the work of the New Saint is reclaiming beauty while also disrupting capitalism and overconsumption. So how can beauty help us access the sublime and the transcendent? When I surrender to beauty, I’m letting go of the ways in which I’m protecting and guarding myself. I’m allowing myself to expand, and I’m letting go of the sense of who I think I am, and then beginning to experience and touch into the actual expression of spaciousness. And when I do that, things get more fluid and more inviting. The world becomes less antagonistic, less rigid, less sharp. It becomes more translucent for me when I’m surrendering and opening. And that is the experience of the sublime. That translucent fluidity really is about connecting to this ultimate experience of emptiness itself. But it’s not about materialism. And so instead of accumulating luxury goods that I can’t afford, I connect to the energetic expression of beauty, which feeds a deeper sense of self-worth. That self-worth is about me wanting not to suffer and wanting to actually experience ultimate liberation.

Let’s go a step further and talk about desire. You say that yearning is the first step in touching the divine. How have you learned to work with and channel yearning? You have to want to get free. Desire or yearning is the last thing we give up before ultimate enlightenment. That yearning for enlightenment is going to take us to the threshold, and to go beyond that threshold, we have to let go of wanting to get free, which I think will be a really hard choice to make. But I am training myself to yearn for things that lead to freedom, liberation, fluidity, and movement, not to continue yearning for the things that create rigidity and separateness. And the more I yearn and the more I practice, the more I begin to experience what freedom is, so I know that this is what I should be focusing on: not the rigidity but the experience of getting open and clear and translucent and fluid. That’s it. And so I just start yearning for it. In the same way that we yearn for our bad habits, we can start yearning for experiences of liberation.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.