Nichiren Buddhism

Nichiren Buddhism is a popular form of Mahayana Buddhism founded on the teachings of the 13th-century Japanese Buddhist priest Nichiren and rooted in the Lotus Sutra. It teaches that enlightenment isn’t reserved for monks or future lives—it’s possible here and now for everyone. This guide examines the life of Nichiren, his teachings, and the global movements that continue to carry his message today.

Table of contents

- What Is Nichiren Buddhism?

- The Life and Times of Nichiren Daishonin

- The Lotus Sutra in Nichiren Buddhism

- Core Practices: Daimoku and Gongyo

- The Gohonzon and Three Great Secret Dharmas

- The Ten Realms and Mutual Possession

- Nichiren Schools and Lineages

- Soka Gakkai and Global Nichiren Buddhism

- Nichiren Buddhism and Social Engagement

- Buddhahood in Everyday Life

- Gosho : The Writings of Nichiren

What Is Nichiren Buddhism?

Nichiren Buddhism is a Japanese school of Mahayana Buddhism founded in the 13th century and practiced by millions worldwide. It is based on the teachings of the Buddhist priest Nichiren, who taught that the Lotus Sutra contains the complete and final message of the historical Shakyamuni Buddha. According to Nichiren, all people, not just monks or scholars, can attain buddhahood through sincere faith in this teaching.

For the times in which he lived, Nichiren’s message was both radically inclusive and uncompromising. He insisted that the Lotus Sutra alone revealed the Buddha’s true intent, and that chanting its title was the key to awakening in this life. Unlike the many schools of Buddhism tied to powerful monasteries, royal patrons, and wealthy aristocrats, Nichiren Buddhism offered an accessible path to laypeople, including peasants, women, and outcasts. Nichiren affirmed that enlightenment was not a distant ideal reserved for monastics but could be achieved within the struggles of work, family, illness, and conflict.

Nichiren’s teachings also marked a shift in how scriptures were interpreted. While most Buddhist schools relied on numerous canonical texts, Nichiren centered his entire doctrine and practice on just the Lotus Sutra. The vast collections of sutras, commentaries, and detailed philosophical treatises are too complex for the average person to study without monastic or academic training and a lot of free time. By concentrating the focus solely on the Lotus Sutra, the path becomes much easier for people to follow.

Today, Nichiren Buddhism encompasses a variety of traditions and organizations, each interpreting Nichiren’s teachings in different ways. Despite their differences, all refer back to the Lotus Sutra, the practice of chanting, the belief in the transformative power of faith in action, and the pursuit of personal happiness and social betterment through active engagement with the world.

The Life and Times of Nichiren Daishonin

Nichiren Daishonin (1222–1282) lived during Japan’s Kamakura period (1185–1333), which was marked by civil war, widespread famine, and natural disasters. Many in Japan believed they were living in a degenerate age called mappo, when the Buddha’s teachings would decline and lose power, as foretold in numerous Buddhist scriptures. Against this backdrop, Nichiren came to believe that only the Lotus Sutra could restore Buddhism and bring peace to society.

Born to a poor fishing family in Awa Province, Nichiren began his life as a Buddhist monk at a local temple of the Tendai school (Ch.: Tiantai), which revered the Lotus Sutra as the highest of the Buddha’s teachings. In the Tendai tradition, monks study the doctrines and practices of all the schools of Japanese Buddhism. Nichiren studied at many of Japan’s major temples, examining the doctrines of Pure Land, Zen, and more esoteric schools of Buddhism. Over the course of twenty years, Nichiren became convinced that devotion to the Lotus Sutra was the only path for the age of declining dharma.

On April 28, 1253, he publicly declared his position and began teaching the practice of chanting the title of the Lotus Sutra. His adamant rejection of other schools and criticism of political leaders led to violent opposition. In 1260, as a result of his public criticisms of the Pure Land movement, one of the most popular forms of Buddhism at that time, he was attacked and nearly killed—the first of multiple attempts on his life. In 1271, he escaped execution when a meteor flashed above the executioner’s head and his captors fled in panic. Nichiren repeatedly fell in and out of favor with the royal family and the Buddhist establishment.

Nichiren’s teachings emphasized the capacity of ordinary people—including women, peasants, and those without formal education—to attain buddhahood in this lifetime. This inclusivity was revolutionary at a time when Buddhist practice was dominated by elite monastic traditions. Nichiren believed that sincere faith in the Lotus Sutra offered a direct and accessible path to enlightenment. Practice was not about scholarly knowledge or ritual purity but about transforming one’s life through faith and moral action.

Nichiren was persecuted, and his teachings were suppressed for most of his life. His final years were spent in poverty and exile. But by this time, he had laid the foundations for a new form of Buddhism that prioritized faith, individual dignity, and active engagement with the world. Nichiren’s concern for the well-being of ordinary people and his belief in their inherent capacity for enlightenment distinguish his approach from Buddhism. His life story of conviction and resilience continues to inspire practitioners.

The Lotus Sutra in Nichiren Buddhism

The Lotus Sutra, one of the most widely recognized Buddhist scriptures, serves as the foundation of Nichiren Buddhism. Some scholars date its oldest textual layers to the 1st century BCE, and it wielded considerable influence throughout East Asian Buddhist history. Nichiren believed it was the Buddha’s final and most complete teaching—one that revealed the full potential of human life. For him, the sutra was not just a text for study but the living dharma itself.

Nichiren taught that the title alone contained the essence of the sutra. Chanting its name Namu Myoho Renge Kyo was equivalent to practicing all the teachings of the Lotus Sutra. It was how one could “read with the body” (Jpn.: shikidoku), not just with the eyes or intellect. Rather than rely on monastic ritual or doctrinal mastery, Nichiren emphasized that sincere chanting could awaken one’s inherent capacity for enlightenment.

Since the Lotus Sutra affirms that all beings can attain buddhahood, Nichiren saw this as a direct challenge to traditions that restricted practice and knowledge to the monastics and elites. Chapter 16, “The Life Span of the Tathagata,” is especially important. In it, the Buddha reveals that his awakening occurred in the remote past and that his presence continues in the world; thus, he and his teachings are accessible here and now for anyone, not just in hard-to-read scriptures that require a lifetime of study. This concept of Buddha’s eternal activity and presence has influenced many branches of Mahayana Buddhism, and it gave Nichiren’s followers a way to see practice as participating in a living transmission.

Because the Buddha is ever-present, the world is not fixed in suffering. The Lotus Sutra teaches that this human world can become a buddha-field—a pure land—through the transformation of human conduct. When people sincerely follow the sutra, they not only transform their lives but also contribute to the purification of society.

The Lotus Sutra strongly emphasizes the karmic law of cause and effect in our lives. It promises that anyone who reads, recites, teaches, or copies even a single phrase will receive immeasurable karmic benefit. Nichiren took these promises literally. For him, practice was a karmic engine. Practice meant action, and action brought change—personally, karmically, and collectively.

Core Practices: Daimoku and Gongyo

Nichiren Buddhism emphasizes two daily practices: chanting the daimoku and performing gongyo. These practices are typically performed in the morning and evening, serving as a moral anchor and an expression of one’s commitment on the path to buddhahood.

The daimoku, or “title,” refers to the Japanese phrase Namu Myoho Renge Kyo, meaning “homage to the Lotus Flower of the Sublime Dharma Scripture,” an expression of praise for the full title of the Lotus Sutra (traditions Romanize this title in different ways, for example Nam Myoho Renge Kyo). Nichiren taught that this phrase contained the essence of the Lotus Sutra, and chanting it concentrated the sutra’s meaning into a single, powerful, accessible form. He likened its function to pulling the main cord of a fishing net: When one chants, all aspects of life are set into motion.

Gongyo, meaning “assiduous practice,” consists of reciting excerpts from Chapters 2 and all of Chapter 16 of the Lotus Sutra, followed by silent prayers and daimoku chanting. The selections from Chapter 2 emphasize the universality of the Buddha’s wisdom, and Chapter 16 reveals the eternal nature of the Buddha’s life and presence. These prayers often include gratitude for life, remembrance of ancestors, and the aspiration for personal growth and collective well-being.

This ritual structure is rooted in older East Asian Buddhist traditions, but Nichiren reshaped them around the Lotus Sutra and his view of accessible practice. Gongyo also reenacts the “Ceremony in the Air,” a pivotal and dramatic moment in the Lotus Sutra where the Buddha rises into the sky and teaches a vast cosmic assembly of buddhas and bodhisattvas. Performing gongyo is understood as symbolically participating in that event.

Together, daimoku and gongyo form the basic rhythm of Nichiren Buddhist life. Many practitioners describe them as energizing the morning and grounding the evening, framing each day with focus, clarity, and intention. Rather than being treated as obligations, these practices are an active expression of one’s vow to confront life with courage and awareness.

Interested in chanting the daimoku? Watch a four-part video by Myokei Caine-Barrett, a bishop in the Nichiren Order of North America.

The Gohonzon and Three Great Secret Dharmas

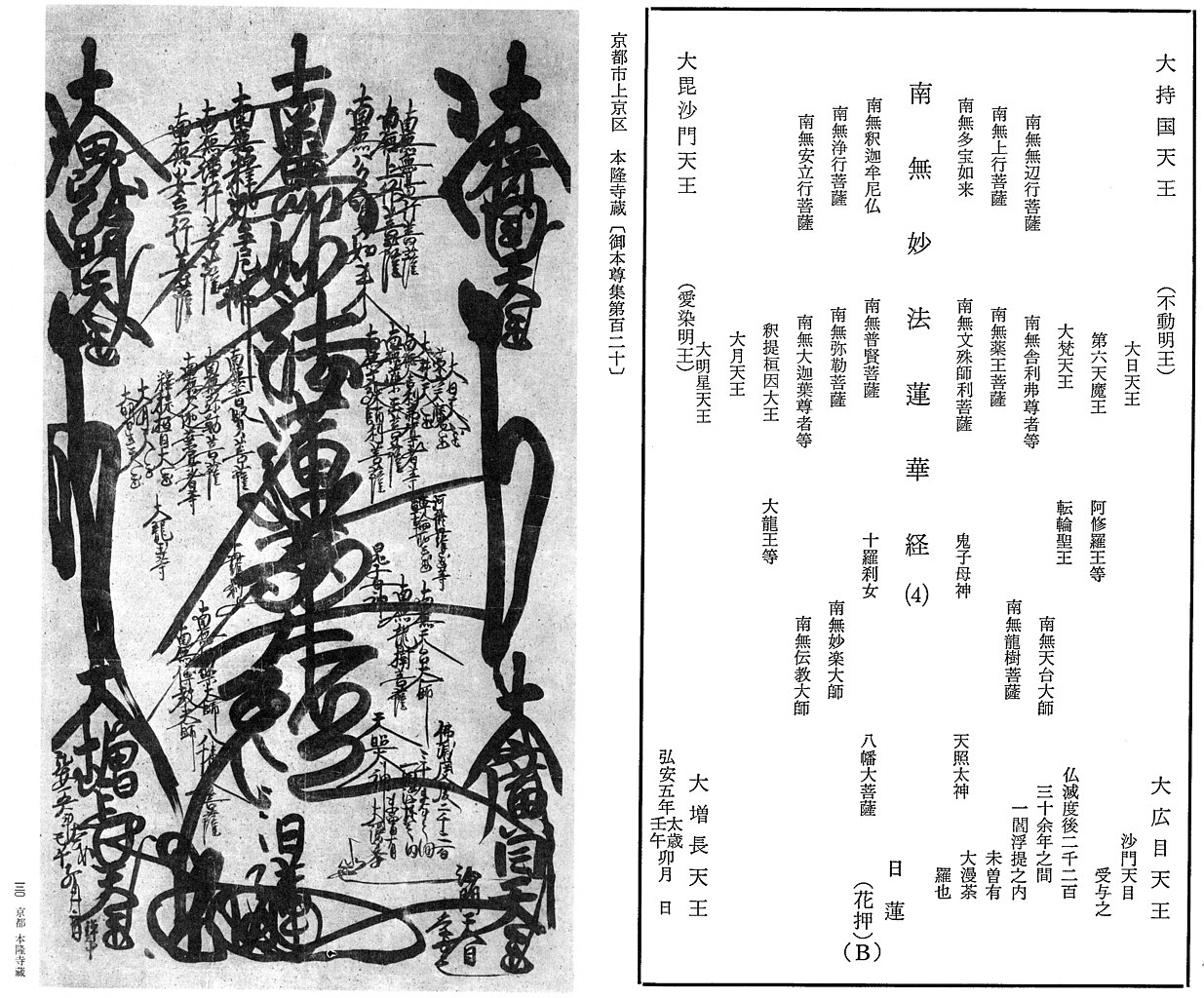

The gohonzon is the central object of devotion in most forms of Nichiren Buddhism. Typically rendered as a calligraphic mandala, it depicts the Buddhist cosmos revealed in the Lotus Sutra. Rather than portraying a deity or external source of power, the gohonzon functions as a mirror of the practitioner’s capacity for awakening.

Nichiren began inscribing mandala-style gohonzon during his exile on Sado Island in the 1270s. Each of these works features the daimoku at the center, surrounded by the names of figures from the Lotus Sutra, including buddhas, bodhisattvas, and protective deities. The central placement of the daimoku represents the unity of the practitioner with the dharma, while the surrounding figures illustrate that all life is mutually supporting enlightenment. Nichiren described it as a visual representation of the “Ceremony in the Air,” the cosmic gathering of buddhas and bodhisattvas in the sutra. In this way, the gohonzon presents enlightenment not as an abstract idea but as a condition inscribed within ordinary life.

The gohonzon is one of the three great secret dharmas (Jpn.: sandai hiho) that form the core of Nichiren’s doctrine. The first is the daimoku, which expresses the essence of the sutra’s teaching. The second is the gohonzon, which provides a physical and visual focus. The third is the kaidan, or sanctuary: the place where the practice is carried out. Interpretations of the kaidan vary across Nichiren schools. Some view it as a specific temple to be built in the future, while others see it as any location where sincere practice occurs. Nichiren introduced these three secrets as an alternative to the dominant forms of Buddhism in his time, which he believed had lost their relevance in an age of declining dharma.

Together, these three elements—voice, image, and space—form the basis of Nichiren Buddhist practice. They replace ritual complexity and monastic hierarchy with a model that is direct, participatory, and rooted in daily life. To chant before the gohonzon is not to venerate an external object but to enact the principle that buddhahood is present within the ordinary self.

The Ten Realms and Mutual Possession

The ten realms in Nichiren Buddhism describe ten distinct conditions of life that all beings experience. These include those living in the six classical Buddhist realms—hell denizens, hungry ghosts, animals, humans, demigods (Skt.: asuras), and divinities (devas)—as well as four higher realms occupied by disciples (sravaka), solitary buddhas (pratyekabuddha), bodhisattvas, and buddhas. This framework draws on earlier Buddhist cosmology that was later systematized by the Chinese Tiantai (Jpn.: Tendai) tradition.

Building on the Lotus Sutra’s teaching that all beings have the capacity for buddhahood, Tiantai thinkers such as Zhiyi (538–597) interpreted the ten realms not only as literal destinations of rebirth but also as internal conditions that manifest from moment to moment. This interpretation became the basis for the doctrine of the mutual pervasiveness of the ten realms (jikkai gogu), which means that each realm contains the potential for all ten. A person consumed by rage (the hell realm) might, in the next moment, act with compassion (the bodhisattva realm). Even someone manifesting the wisdom of a buddha may still experience fear or desire. These conditions are not permanent or sequential; rather, they are interdependent and fluid.

Nichiren adopted this framework and applied it to daily life. For him, each realm was not only a mental or emotional state but also a karmic condition, shaped by prior causes and amenable to change. Chanting Namu Myoho Renge Kyo is a way of calling forth the higher realms and releasing the hold of destructive tendencies. The ten realms also show how personal transformation affects the world. Inner conditions shape how people relate to others, meet challenges, and contribute to their environment.

Contemporary secular Buddhists often interpret the six realms through a similar psychological lens. Some modern interpretations encourage practitioners to observe which realm dominates their thoughts or behavior in a given moment, and to cultivate awareness of how quickly these conditions can shift. In this, practice becomes a tool for navigating life, rather than an escape from it. It is the ongoing ability to move skillfully among these realms, grounded in awareness and supported by consistent practice.

Nichiren Schools and Lineages

As it exists today, Nichiren Buddhism is not a unified tradition but a collection of distinct schools that trace their origins to Nichiren. After he died in 1282, his disciples preserved and interpreted his teachings in various ways. Over time, this led to fragmentation and the emergence of multiple lineages, each emphasizing different aspects of his doctrine and practice.

One of the earliest divisions arose between those who viewed Nichiren as a reformer within the existing Tendai Buddhist tradition and those who saw him as a buddha in his own right. These views shaped differences in ritual focus, institutional structure, and doctrinal authority, including opinions on the gohonzon and the role of clergy.

Nichiren Shu is one of the oldest and largest schools of Nichiren Buddhism. It maintains a more traditional approach, combining the chanting of Namu Myoho Renge Kyo with the recitation of the Lotus Sutra and other practices. Nichiren Shu emphasizes Nichiren’s continuity with the Tendai tradition and sees him as a great teacher rather than a buddha. Its temples and training centers still serve both clergy and lay practitioners.

Nichiren Shoshu, by contrast, views Nichiren as an eternal buddha. This school focuses exclusively on the chanting of Namu Myoho Renge Kyo and veneration of the gohonzon, which it holds can be transmitted only through its head temple, Taisekiji. Nichiren Shoshu has strict rules regarding the orthodoxy of its practice and the authority of its high priest.

Other schools, such as Kempon Hokke-shu and Honmon Butsuryu-shu, also have unique interpretations of Nichiren’s writings and distinct ritual traditions. Despite their differences, all schools maintain the central importance of the Lotus Sutra and the chanting of its title as the basis for awakening.

In the 20th century, new movements significantly changed the landscape of Nichiren Buddhism. The largest and most well-known is Soka Gakkai, an offshoot of Nichiren Shoshu that eventually became independent. Another is Nipponzan Myohoji Daisanga, a smaller order of both lay and ordained practitioners best known for its peace activism and the construction of symbolic pagodas around the world. These new religious movements reflect the tradition’s continuing adaptation to contemporary life.

Soka Gakkai and Global Nichiren Buddhism

Soka Gakkai is the largest and most internationally widespread form of Nichiren Buddhism. Founded in 1930 as an educational reform society in Japan, it gradually developed into a lay Buddhist movement grounded in Nichiren’s teachings. Its founders, Tsunesaburo Makiguchi (1871–1944) and Josei Toda (1900–1958), were both educators who emphasized the potential of Buddhist practice to foster personal responsibility and social harmony. Soka Gakkai focuses on chanting Namu Myoho Renge Kyo, studying Nichiren’s writings, and applying Buddhist principles to daily life.

After World War II, the organization experienced rapid growth under Toda’s leadership. In 1960, Daisaku Ikeda (1928–2023) became its third president and guided its growth into a global movement. Soka Gakkai–affiliated groups have spread to more than 190 countries and territories and were eventually unified under the name Soka Gakkai International (SGI), which promotes peace-building, educational initiatives, and cultural exchange as expressions of engaged Buddhist practice.

SGI is distinct for its decentralized, lay-led structure. Local districts host regular small group gatherings called zadankai, where members share their experiences and study Nichiren’s teachings. These meetings foster mutual encouragement and practical application, serving as the primary setting for practice and community life.

SGI also participates in international forums, consulting with groups such as the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). Through affiliated organizations like the SGI Office for UN Affairs, it advocates for nuclear disarmament, environmental sustainability, and human rights, linking Buddhist ethics with global citizenship.

Frequently cited as one of the most diverse Buddhist movements in the world, SGI membership encompasses a wide range of ethnic, cultural, and socioeconomic backgrounds. In the United States, it has provided a spiritual home for many Black American Buddhists and other historically underrepresented communities seeking inclusive and socially conscious religious communities.

While SGI is the most prominent representative of Nichiren Buddhism, other groups also maintain international communities. Nichiren Shu has established temples throughout the Americas and Europe, and movements like Rissho Kosei Kai have developed related forms of practice grounded in the Lotus Sutra. All of these groups demonstrate the adaptability of Nichiren Buddhism to modern social and cultural contexts.

Nichiren Buddhism and Social Engagement

Nichiren Buddhism has long emphasized the connection between personal practice and social responsibility. This idea originates with Nichiren himself, who argued that social disorder and suffering cannot be separated from a society’s spiritual condition. In his 1260 treatise, Rissho Ankoku Ron (“On Establishing the Correct Teaching for the Peace of the Land”), he asserted that lasting peace could be achieved only through embracing the Lotus Sutra, which he believed upheld the inherent dignity and potential of all people.

Nichiren’s insistence on confronting religious, political, and social injustice continues to shape how many followers understand Buddhist practice. He even critiqued government officials and prominent religious figures, often at significant personal risk. For Nichiren, public advocacy was not outside the domain of religion; it was its rightful expression.

Contemporary Nichiren organizations draw from this foundation to support peace, human rights, and social justice. While approaches vary across traditions, many believe personal integrity is inseparable from ethical engagement with the world.

Among modern movements, Soka Gakkai International (SGI) promotes education, dialogue, and cultural exchange as part of its global peace work. Through its affiliated offices, it participates in international forums and campaigns for nuclear disarmament, sustainability, and human rights. Its philosophy of “human revolution” emphasizes personal growth as the engine of lasting social change. Nipponzan Myohoji Daisanga, a smaller but committed order of lay and monastic practitioners, focuses its efforts on peace activism. The group is known for building “peace pagodas” around the world and organizing walks for peace and nonviolence. Their practice of chanting the Lotus Sutra’s title is a form of personal cultivation and public protest—a visible affirmation of nonviolence and solidarity.

Other groups, such as Rissho Kosei Kai, emphasize interfaith dialogue and humanitarian outreach. Although differing in structure and emphasis, these movements share a commitment to applying the teachings of the Lotus Sutra to the modern world’s conditions.

These efforts place many Nichiren-inspired movements within the broader tradition of Engaged Buddhism, which seeks to apply Buddhist values to urgent social, political, and environmental challenges. While the label is more commonly associated with other traditions, Nichiren Buddhism has long maintained that religious practice and social action are inextricably linked.

Buddhahood in Everyday Life

In Nichiren Buddhism, enlightenment is not reserved for monastics or renunciants. It is considered fully attainable by ordinary people within the circumstances of everyday life. This view reflects the Lotus Sutra’s central teaching: that all beings possess the potential for buddhahood.

Rather than aiming to escape the sufferings of samsara (the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth), Nichiren taught that one can attain buddhahood by transforming suffering from within. Chanting the Lotus Sutra’s name enables practitioners to call forth the wisdom, courage, and compassion already present in their lives. Over time, consistent practice shifts how one experiences hardships: Problems are no longer seen as obstacles but as opportunities for growth and insight.

Nichiren drew on the Lotus Sutra’s vision of the “buddha-field” or “pure land” to describe this process. Unlike some Pure Land schools, which envisioned a realm of rebirth far removed from this world, Nichiren taught that the human world could itself become a purified buddha-field. This transformation is not dependent on external conditions, as it is revealed through one’s words, thoughts, and actions. Chanting serves as karmic purification, not to escape the world but to reveal the dignity already inherent in it.

This perspective grounds Nichiren Buddhism’s emphasis on socially engaged practice. Chanting is a form of personal cultivation, and it also contributes to collective well-being. For many practitioners, enlightenment means responding to daily life with wisdom and compassion, both in our personal relationships, at work, within our community, and in society. The goal is not transcendence but a transformation grounded in the conviction that each moment holds the possibility for awakening and change. Nichiren Buddhism offers a path that begins exactly where one is. Enlightenment, in this view, is not a distant ideal but a potential realized through sustained effort in our ordinary lives.

Gosho: The Writings of Nichiren

The writings of Nichiren, known collectively as the Gosho, are central to the study and practice of Nichiren Buddhism. Composed primarily between the 1250s and his death in 1282, these texts include letters, treatises, and sermons addressed to followers and opponents. They provide doctrinal foundations for Nichiren schools and serve as sources of encouragement and guidance.

Nichiren’s writings address a wide range of themes, from polemical critiques of rival teachings to personal letters offering encouragement during persecution and hardship. What distinguishes many of his letters is their accessibility: Nichiren often wrote them in the vernacular style of the time, rather than in classical Chinese, which he used for his formal treatises and was commonly used among educated elites in East Asia. This decision reflects his conviction that all people, not just monastics or educated elites, possess the capacity for buddhahood and deserve access to the teachings.

Many of these letters were written to laywomen, including samurai wives, widows, and nuns. In them, Nichiren affirms women’s potential for enlightenment and urges them to maintain their practice of chanting the Lotus Sutra’s title, uphold its teachings, and hold on to their faith in the face of adversity. At a time when most Buddhist institutions marginalized female practitioners, these writings have a distinctly inclusive understanding of religious agency.

The Gosho is widely read and quoted in modern Nichiren traditions, particularly in lay movements like Soka Gakkai. Passages are studied in meetings, referenced in daily practice, and consulted for guidance and insight. Nichiren’s writing style was direct, passionate, and filled with concrete analogies that still resonate with modern readers. Common themes include the power of sincere faith, the courage to face obstacles, and the inseparability of individual and societal transformation.

Beyond their religious significance, the Gosho provides insight into the social and political conditions of 13th-century Japan. Nichiren’s responses to famine, persecution, exile, and political unrest reveal a worldview shaped by the Lotus Sutra’s promise of universal buddhahood. After centuries, Nichiren’s voice continues to speak to the challenges of everyday life, offering clarity, conviction, and encouragement.

Buddhism for Beginners is a free resource from the Tricycle Foundation, created for those new to Buddhism. Made possible by the generous support of the Tricycle community, this offering presents the vast world of Buddhist thought, practice, and history in an accessible manner—fulfilling our mission to make the Buddha’s teaching widely available. We value your feedback! Share your thoughts with us at feedback@tricycle.org.