Alison Bechdel’s latest graphic memoir, The Secret to Superhuman Strength, begins in full color and in media res: we walk in on the author-artist at home and in training (isolated pandemic-style, one assumes), huffing and puffing as she does weighted step-ups on a chair (Hup! Hoh!), karate-kicks the air (Hi Yah!), and flows through a yogic chaturanga (Foof, Grink-k-k).

The Secret to Superhuman Strength

By Alison Bechdel

Mariner Books, May 2021, $24, 240 pp., paper

This opening number, with its full-spectrum splashes and classic comic sound effects, may come as a shock to the initiated reader. Bechdel, after all, is best known for her two memoirs, both meditative, hyperliterate works in soft monochromes. First and most prominent is Fun Home, a “family tragicomic” rendered in blues about Bechdel’s own coming out and her relationship with her closeted father (“the dad book,” as Bechdel dubs it, which has been adapted into a Broadway musical and will soon also be a movie musical starring Jake Gylenhaal). Second is the all-red companion piece, Are You My Mother?, a “comic drama” about psychoanalysis and Bechdel’s relationship with her mother (“the mom book,” naturally). Now, with The Secret to Superhuman Strength, Bechdel has come home to a story that is all her own and a subject that is, at least on its face, a little lighter: Bechdel’s relationship with exercise. “Perhaps my bookish exterior belies it,” her narrator deadpans modestly, “but I’m something of an exercise freak.”

Named for a mail order pamphlet Bechdel once ordered as a child in the hope of achieving physical invincibility (“a badly reprinted martial arts instruction book,” as it turned out), The Secret to Superhuman Strength quickly reveals itself to be about much, much more than exercise. It’s a rangy exploration of mind-body dualism, a semitraditional hero’s journey, a seeker’s quest for transcendence, a Künstlerroman, and, eventually, a love story. It is, in Bechdel’s words, “how the pursuit of fitness has been a vehicle for me to something else.”

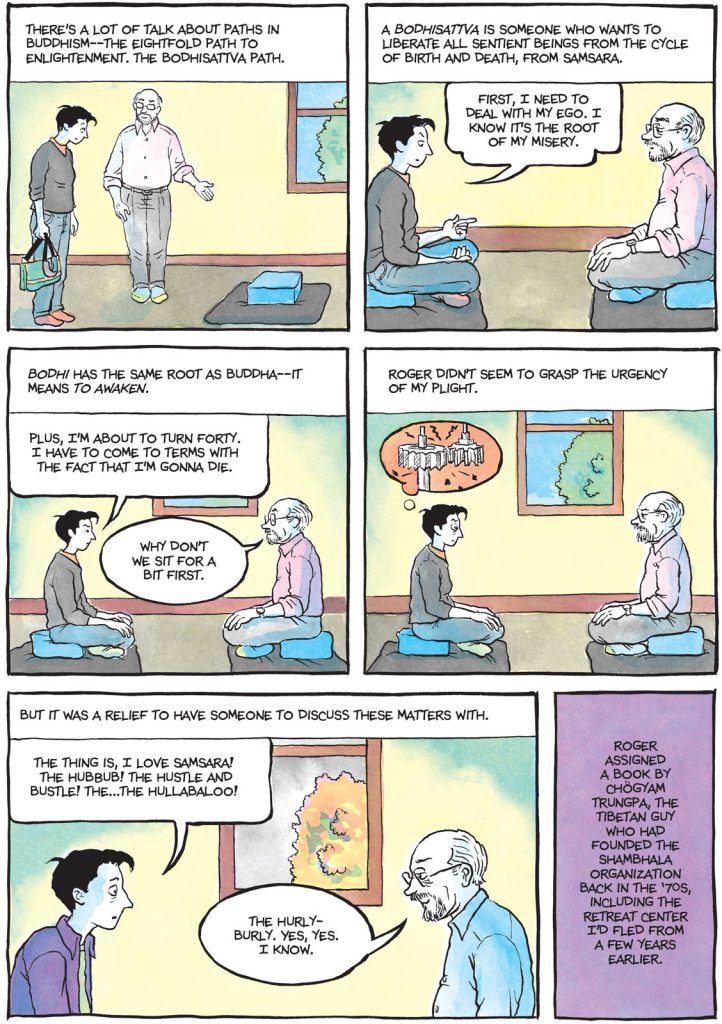

Bechdel uses the exercise motif (or, more broadly, the theme of minds and bodies) as an excuse to explore thinkers and histories spread far and wide across her web of influences and interests. In The Secret to Superhuman Strength, Margaret Fuller and Samuel Taylor Coleridge collide with Chögyam Trungpa and Shunryu Suzuki; the poems of Adrienne Rich play off the aesthetics of L.L. Bean and Patagonia; a psychosexual fascination with alpine topography flows into a reading of Jack Kerouac’s Dharma Bums. Nothing is beyond Bechdel’s reach; nothing is outside the realm of possibility.

The eclecticism of sources and the free range with which Bechdel allows them to interact is a brilliant strategy for both self-revelation and deflection, as far as memoirs go. And it’s not just the volume of Bechdel’s sphere of references that is notable—it’s the particular ways in which she plays them off one another. Bechdel has a way of calling up anecdotes and memories and references that feel, while they are happening, as if they are generating the narrative momentum of traditionally blocked scenes, gearing up for some kind of transformation or lesson learned, a step forward on a well-plotted journey. More often than not, though, the sense of purpose she summons doesn’t quite resolve so much as fade into the next track, with DJ Bechdel spinning the story—one that both is and isn’t really about her—on into the night.

The story flows and flip-flops and doubles back. Bechdel waffles and achieves and regresses, builds strength and loses it.

With its decade-by-decade chapters moving from Bechdel’s birth in 1960 to the present, the memoir is, on its face, clearly and conventionally indexed, while underneath it moves in stranger and more complex ways. It would be disingenuous to describe Bechdel’s style as stream of consciousness—it’s more like stream of memory: it follows the associative chain-linking of a curious mind, while also demonstrating all the ways that current preoccupations and knowledge impose a certain artificial order on the past. There is an odd ease to this should-be-difficult book. It’s easy to move through because it is always moving: the story flows and flip-flops and doubles back; Bechdel waffles and achieves and regresses, builds strength and loses it. “Advancing, retreating. I seemed to be getting nowhere fast,” she writes.

Fitness is not the only way that Bechdel finds and loses herself: her workout book is also about her work. When it comes to her creative process, Bechdel demonstrates a predilection for manic all-night fits, riling herself up to “a brief moment of exultation before collapsing,” at which point she is often left catatonic and physically ill. Her life is “governed by these cycles of exertion and collapse,” she writes. As she works out and works herself into states of pain and ecstasy and oblivion, Bechdel changes her mind and body, articulating a consistent through-line of self and character.

There was no way I wasn’t going to be compelled by this book. Like Bechdel, I am a bookish-presenting person with a lifelong exercise habit and a tendency toward immersive dabbling (call it being a serial monogamist for workouts). I also (like Bechdel, it seems) forge intense attachments to these activities while both benefiting from and downplaying affiliation with the communities around them. When Bechdel finds her way to a dojo in the 1980s, she admits that the “real appeal of karate” may just be “the experience of union as we moved and breathed in sync, in a collective trance.” She bails on the sport a few years later after she escalates an argument with a stranger in the New York subway and gets punched in the face for real (“it was not a Zen slap . . . [but] I experienced a kind of enlightenment”). Some years later, when Bechdel tries regular attendance at a Shambhala meditation center, she confesses to a teacher that she “hate(s) sitting with other people” and retreats home to cycle solo on her spin bike.

I get it. I don’t think of myself as a “joiner,” and yet I regularly put myself in situations where I am moving in tandem with collectives of others, feeding off the strong, generic force of the sum of their individuality, doing the same as everyone else while indulging in the fantasy of myself as more observer than participant. I believe in the value of community; I just prefer to experience it (or at least pretend to) alone.

Like Bechdel, I have also twisted a passion for exercise into my creative work in ways that both do and don’t make sense. My reverence approximates worship, elevating habit to something more like ritual—a series of actions intended to invoke something bigger and more important than the sum of their parts. (The bodily attunement of exercise, Bechdel says, makes her feel “part of — dare I say one with?—something larger than myself.”)

Most of my working life as a writer is spent chasing down a very particular feeling: a certainty and sense of purpose so totalizing that it transmogrifies self-importance into self- obliteration. The moment when the work is working, when creation starts to really happen (“Oh, God, that moment!” Bechdel rhapsodizes to an ex, talking about writing). It’s rare but powerful when it comes from stringing words together on a page, and the feeling—or a passable version of it, anyway—is more reliably achieved through something more basic, like the repetitive, energetic, semi-senselessness movement of the body. Working out is both simulacrum and gateway—creative ecstasy’s dependable, ready-made cousin.

So I understand both Bechdel’s pursuit and its plights. My kinship is challenged, however, by the strong masochistic element that asserts itself in her various regimens. What Bechdel soft-pedals at the beginning of the memoir as being “the vigorous type” with “a bit of a self-improvement problem” turns out to be something more like a full-bore, life-threatening addiction to pain endurance through labor. To be honest, I’m just not that hardcore.

Though Bechdel troubles her relationship with substances at various periods in her life (sleeping pills and alcohol make repeat appearances), I’d argue that insofar as this is a book that deals with addiction, Bechdel’s primary dependence is on independence itself: she nurses a reliance on the broad American myth of self-reliance. Her workaholism and exercise obsessions are both rituals by which Bechdel confers such a myth.

Bechdel is a supremely self-aware narrator, and her portrait of the artist as a workaholic is offered as a cautionary tale. Even as she summits major success and transforms into the person we know her as—creator of Fun Home, MacArthur-certified genius, feminist icon and Bechdel test eponym—Bechdel’s work life, in her telling, only gets worse. She sketches out the guilty miseries and identity-rattling compromises of artistic achievement. “Accept a string of awards and honors it would be churlish to turn down, each one leaving you feeling more depleted and foolish than the last,” she writes, reimagining this period of her life as instructions for a “Semi Sadistic” high intensity workout. At the summit, after all, there is the unavoidable implication of descent: “Wonder if your life might all be downhill from here.”

And yet it’s hard to say that the tale is entirely cautionary. After all, Bechdel’s life has not gone downhill at all but onward—toward the creation, in fact, of this very stunning and inventive book. In theory, being a workaholic is no more enviable than being any other kind of addict; in practice, it’s hard to fully rid oneself of a mindset that valorizes such inhuman shows of output when the results are as extraordinary as Bechdel’s work is. Even though Alison Bechdel’s self-punishing work habits look like an unholy nightmare I wouldn’t wish on anyone, a very tiny, recalcitrant part of my brain can’t help but think: would I be more successful, and creatively fulfilled, and better off if I did it her way? Should I just work harder? Should I work like that?

Here’s the thing: the real prize of artistic success isn’t so much money or fame as the time and permission that are their dividends. Time to make art because you aren’t doing something else to earn a living and stay alive; permission to make the art you want because your talent has been signed off on, your vision preapproved for recognition. And if they can allow themselves to accept such a gift (easier said than done, I’d bet, if Bechdel’s example is anything to go on), what this affords an artist is the chance to follow their curiosity, to take risks, to survive the fallow moments of rest, or failure, or removal that may eventually lead to great works.

Though we see Bechdel chafe against such freedoms and resist them in The Secret to Superhuman Strength, finding new and old ways to constrain and punish herself, she also stretches creatively to produce something as idiosyncratic and wide-ranging as the very memoir we have in hand. Whether she believes it to be so or not, her success is the very thing that has permitted her to prowl across the expanses of her eclectic and unlikely interests hunting for through-lines of connectivity, to exercise the right to formal invention, to pull together a narrative that resists the obvious. Which is to say: The Secret to Superhuman Strength is a wonderful book that no one but Alison Bechdel could have made. Also, you’d have to already be Alison Bechdel in order to try.

No more than twice per decade, Bechdel pauses the relentless flurry of activity to savor full, two-page, black-and-white spreads that depart stylistically from the rest of the comic. Here, lines bleeding into one another, ink spreading blurrily across a damp page, giving the impression of a hasty capture, a one-shot take. It’s the kind of artwork that makes the moment of its own creation visible somehow, inviting the viewer to picture, almost involuntarily, the way the brush moved across the page.

These are quiet scenes punctuated by precise realization, and they depict moments when Bechdel is unavoidably connected to the world around her: transcendence, but the kind that comes on real slow—awe that seeps into you rather than knocking you flat. “I sensed my whole life spooling out before me, far beyond the horizon of the Allegheny Plateau,” she narrates over a soft portrait of her child-self skiing down a hill. “If you can manage to see past everyday reality, where subject and object hold sway, to the view where it’s all one thing, unified and absolute, there’s nothing to relate to,” she writes over a portrait of herself walking across a frozen lake at the end of her 20s, wintering koi suspended in the ice below her feet.

Bechdel stretches creatively to produce something as idiosyncratic and rangy as the memoir we have in hand.

Set against the busybody bluster and kinetic pace of the rest of the memoir, these quiet, out-of-time way stations are stunning. They also reflect a counterintuitive fact about big realizations: rarely does a person just have one and then live forever with its consequences. More often, the moment of truth is the one you keep coming back to, the lesson you keep relearning. An epiphany is more recognition than discovery, more homecoming than travel.

More than it is about exercise, The Secret to Superhuman Strength is a book about process. Bechdel signals from the very beginning of the book where’s she’s going with it: “to embrace my interdependence,” she declares. The borders between self and other erode. Bechdel comes to recognize (and forget, and recognize again) her essential attachment to—and, more crucially, reliance on—the fragile, temporary, mortal world.

We watch her light out in 2013 on “a light, fun memoir about my athletic life that I could bang out quickly.” (Spoiler: it’s not quite like that.) She dubs this “the fitness book” and proceeds to spend the next eight years oscillating between avoiding it and muscling through it, up to her usual tricks.

“The path is the destination,” Bechdel tells herself one day as she scrambles up a hill, in a creative funk over the book we are reading, and then, ironic and self-deprecating as always: “bla, bla, bla.” With the bodhisattva path on her mind, she dunks her head under a waterfall that doses her like another Zen slap: “My life was going to end,” she writes. She admits that she’s been avoiding finishing her book out of perverse attachment to the struggle, out of a wish to continue on with her work, and her life, in perpetuity.

As it nears its close, Bechdel’s already-meta memoir goes one better. Over the past decade-plus of Bechdel’s tale, we have witnessed the optimism, holism, flexibility, and well-being of her partner, artist Holly Rae Taylor, ease their way into the joints of the Bechdel work-machine. And in the end, Superhuman Strength literalizes the release from independence Bechdel has spent a lifetime (or at least a memoir) processing: as the deadline on the fitness book looms, she runs out of time to shoulder the work herself and enlists her wife to do the laborious work of colorizing the pages in a collaboration forced by necessity. The book doesn’t just express interdependence—it manifests it.

♦

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.