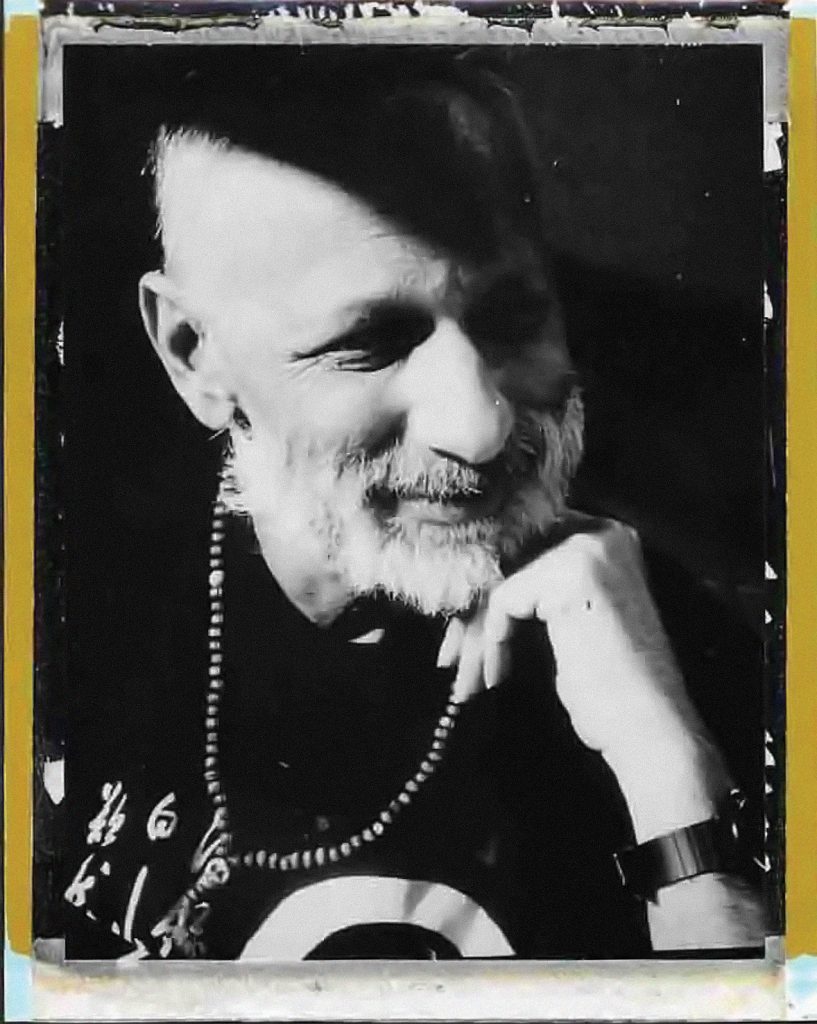

In 1991, as a 16-year-old student, I found myself having lunch at the Spring Street Café with my Uncle Rick, Allen Ginsberg, and a few of their friends. It was my first visit to New York City, and—having read The Dharma Bums the previous summer—I was completely starstruck by the Beat royalty at the table. My “Uncle Rick” was Rick Fields, a pioneer of American Buddhist journalism and the author of How the Swans Came to the Lake: A Narrative History of Buddhism in America. During that lunch in Soho, much excited conversation revolved around another project that he was deeply involved in, the launch of a new Buddhist magazine called Tricycle. The first issue had just been released, though the discussion of its significance for the dharma in America was well over my head. One of the few details that I do remember was that someone was deeply vexed about how many copies of the magazine, with its portrait of His Holiness the Dalai Lama on the cover, would end up on floors or in trash cans rather than being properly stored in a clean, high place or carefully burned “as Tibetans would do.” Rick caught my confused look and smiled with his eyebrows raised in a way that suggested sympathy for these concerns around cultural sensitivity while also suggesting that focusing on where the physical magazine ended up after someone finished reading it was maybe missing the point of the whole endeavor.

How the Swans Came to the Lake: A Narrative History of Buddhism in America

by Rick Fields

Shambhala Publications, Feb. 2022, $29.95, 592 pp., paper

That day, I never would have imagined that in less than ten years, Rick would be dead from lung cancer at the age of 57 or that twenty years later I would be a college professor with a PhD in Buddhist Studies or that thirty years later I would be writing in the pages of the magazine they were discussing to celebrate the fortieth anniversary edition of How the Swans Came to the Lake. I suspect that were he still able to, Rick might greet these developments with the same raised eyebrow of bemused acceptance that he offered at that lunch.

I had a number of conversations with Nikko Odiseos, the stalwart president of Shambhala Publications, about creating a significantly revised and updated version of the book, including additional chapters to address the past thirty years (a revised third edition was published in 1993, when Rick was still alive). After a year of attempts that led nowhere, I concluded that this was a misguided effort to make the book something it is not. There is simply no way to continue the story from where Rick left off. The intimate narrative style that defines the book would be impossible to replicate in describing an American Buddhism that has erupted into the mainstream in ways quite unimaginable forty years ago. The cast of characters is not yet equal to the sands of the Ganges, but it has multiplied from the dozens of prominent figures portrayed in the book to hundreds, if not thousands. Further, these more recent developments in the story of American Buddhism have been examined in a growing collection of excellent books by scholars and journalists. Letting go of the idea of a fully updated new edition, I proposed instead writing an essay that would contextualize the book as a classic of American Buddhist literature.

The book is the closest we have to an American contribution to the tradition of Buddhist historiography that announces the arrival of Buddhism in a new land by telling the story of how it got there. Rick was directly involved with many of the most important Buddhist teachers in the United States from the 1960s until his death in 1999, and his book retains the fresh quality of a participant’s eyewitness account. Of course, today we would write parts of the story quite differently, and a number of more recent studies of American Buddhism do just that. Rick understood the story of Buddhism as beginning and ending with the Buddha’s awakening, and he fashioned his book to make the case that the multicultural, diverse, dynamic landscape of Buddhism in America was the perfect environment for awakening in the 20th century—and in that sense, Buddhism in America represented not just an arrival but a homecoming. Rick described early in Swans his own perception of the writing of Buddhist history:

Buddhist history is the record of lineage—of who gave what to whom—not as a dead doctrine but as living truth; it is more a matter of the freshly baked bread than of the recipe. Though lineage is chronological and linear, or seems to be, and the story has gone on for 2,500 years, Buddhism insists on the primacy of the present. Zen masters sometimes talk about locking eyebrows with the ancient patriarchs, and it is in this sense that history—or at least Buddhist history—is never out of date.

This vision of the immediacy of the transmission explored in Swans must be considered alongside a reckoning with the ways in which the story of Buddhism’s journey to the United States has shifted over the past forty years.

How the Swans Came to the Lake announces the arrival of Buddhism in a new land by telling the story of how it got there.

As I attempted to make sense of the book from the vantage point of 2020, as dramatic waves of protests against sexist and racist violence dominated the landscape, I could not ignore the ways in which the structure of How the Swans Came to the Lake reflects a version of American Buddhist history intertwined with the patriarchal and racist histories of America itself. One cannot help but notice that in the earlier editions’ three sections of photographs, only three women are pictured. Both the visual and the narrative contents of the book suggest that the story of Buddhism in America is one dominated by male Asian teachers and their white male students. The book neglects to deal in any substantial way with patriarchy as a force in both Asian and American forms of Buddhism. Beyond the simple fact of the book’s focus on men, there is the issue that a number of the teachers highlighted in the book have since come to be seen as highly controversial figures—still studied for their teachings and presences but also credibly accused of alcoholism, sexual misbehavior or outright abuse, and financial impropriety. Abuse of power in sanghas has come to be recognized as such a widespread phenomenon that the solo-leader model of sangha structure has come under sustained critique in the American context, and many communities have departed from it altogether.

After introducing the origins of Buddhism on the Indian subcontinent, the book’s narrative moves quickly to an examination of “the East” as seen through the history of encounters with “the West.” This is followed by extensive summaries of colonial scholarship and Orientalists in Europe and New England. It is not until the fifth chapter that we first read of Asian Buddhist immigrants to the United States, who fade from the story after that point. This focus on convert Buddhist communities and the marginalization of Asian American Buddhists has been investigated and critiqued by numerous scholars over the past few decades, offering a much more robust understanding of both the ongoing vitality of Asian American Buddhist communities and the racist structures that erase them from much of Swans.

Rick was aware of this problem with the book and reflected upon it in in two notable essays: “Confessions of a White Buddhist: Dharma, Diversity, and Race” (Tricycle, Fall 1994) and “Divided Dharma: White Buddhists, Ethnic Buddhists, and Racism” (The Faces of Buddhism in America, 1998). In the former, he identifies that racism has been “the nightmare squatting at the heartof the American dream since the very beginning.” His essays lay out the anti-Asian racism enacted by the United States government through examination of multiple instances: an 1854 California Supreme Court ruling that disallowed the testimony of a Chinese eyewitness to a murder on explicitly racist grounds; the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882; and the forced internment of 110,000 Japanese Americans in 1942. Beyond these unquestionably racist acts of American history, however, he also identifies the workings of white privilege specifically in the realm of American convert Buddhism. He writes, for example, of the ways that a convert to Buddhism might adopt a Tibetan or Japanese name or style of dress in certain contexts while always having the option of switching back when it is convenient—what we now call “cultural appropriation.” Rick emphasized this point with a hypothetical example that is rather chilling to read in 2022: “But the fact is that when and if it becomes necessary or convenient––in the event, say, of a right-wing fundamentalist Christian coup––white Buddhists could shuck it all and emerge, like Clark Kent knotting his tie as he exits his phone booth, safe and sound.”

The essays, though insightful and groundbreaking in many respects, maintained a naive view of “two Buddhisms” that more recent scholars have shown to be overly simplistic—itself based on the same structures it seeks to question. Immigrant Buddhism (or “ethnic Buddhism,” in the language of the essays) is identified primarily with the devotional, populist, communitarian ethos of Japanese Pure Land traditions, in contrast to the philosophical, meditation-focused, individualist bent of convert Buddhists. While Rick does not sufficiently critique this binary structure, he does suggest that convert Buddhists would benefit greatly by learning from the example of the non-monastic Buddhist communities, notably Japanese Pure Land traditions. “Such a Buddhism,” he writes, “would continue to provide a safe haven for ethnic Buddhist communities from a beleaguered Asia, as well as an experimental crucible for creative and effective adaptations, and would give us all the chance to create a truly liberating, multicultured, many-hued, shifting, shimmering Pure Land of American Buddhism.”

Everything that I know of Rick Fields makes me certain that this vision of an American Buddhism liberated from the karma of racism and white supremacy was a deeply and sincerely held prayer of aspiration. It is equally true that this vision of American Buddhism is not fully reflected in How the Swans Came to the Lake with its focus on Asian male teachers and their white male successors.

When we look at the history of Buddhism as it has moved around the world, we see that the tradition has been transformed through contact with each culture that has adopted it and that each of these cultures has been transformed through its contact with Buddhism. When we read Swans today, we will see reflections of the potential for transformation and liberation promised by the waves of teachers and teachings that reached the American shores between the end of the 19th century and the end of the 20th century. If we read closely, we will also see reflections of the American demons of racism, patriarchy, imperialism, and greed that today remain deeply embedded in the fabric of our nation. Forty years after its publication, How the Swans Came to the Lake is a beautifully constructed mirror through which we may lock eyebrows with our ancestors again and again.

♦

Adapted from the introduction to the fortieth anniversary edition of How the Swans Came to the Lake. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.