Earlier this year, as I was looking through an advance copy of Jhana Consciousness: Buddhist Meditation in the Age of Neuroscience by Paul Dennison, a name jumped out, first on the dedication page and then repeatedly throughout the book: Nai Boonman.

Jhana is an interesting term referring to meditative absorption that arises from concentration practice. There are nine jhanas in total, the first four being rupa (“form”) jhanas, associated with rapture, pleasure, equanimity, and mindfulness. The five higher jhanas (arupa, or “formless”) are said to endow practitioners with supernatural powers, including the ability to walk through walls.

Perhaps the two best-known modern jhana teachers in the West are the German-born Buddhist nun Ayya Khema (1923–1997), who first learned jhanas from classical texts, and Leigh Brasington, who was authorized by Ayya Khema to teach jhanas and who has now been leading retreats for decades. When asked, Brasington had never heard of Boonman. Yet Boonman, as Dennison writes, is an essential link in jhana practice.

Starting in the mid-20th century, the Thai sangha began favoring vipassana (insight) over samatha (concentration) practice, which is used to access the jhanas. Even legendary masters like Ajahn Chah (1918–1992) were careful not to call “jhanas” by their name. But Boonman Poonyathiro, a former monk and meditation teacher in the UK in the sixties, bypassed all this drama. Dennison, a psychotherapist and researcher who has published research on the brain activity of practitioners who have experienced jhana, credits him with sustaining an essential practice whose history dates back to the time of the Buddha.

Boonman turns 90 in August 2022 and because of health and memory issues was not available for an interview. Thus this profile relies heavily on Boonman’s self-published autobiography, From One to Nine (2003), academic writing, and interviews with his wife and students.

Boonman Poonyathiro was born to a Cambodian father and a Thai mother on August 5, 1932, in Ta Prik, a district in northeastern Thailand, the youngest of three children. Boonman’s mother died fifteen days after she gave birth to him.

As Boonman recalls in From One to Nine:

There was a story that after my birth my mother craved gibbon soup. There were plenty of gibbons around that area, and to please her, my father went to the forest to shoot one. Unfortunately, the gibbon he shot was a mother with baby; the mother fell to the ground dead, and the little one ran away. My mother died shortly after this incident and my father for some reason blamed me for her death. He moved away, taking my brother and sister with him, leaving me in the care of a relative of my mother, a spinster named Miss Kuo. I became an orphan overnight.

Miss Kuo died when Boonman was 4, and he was sent to live with an uncle. Then, when he was 7, he went to live at a temple school (Thailand has a centuries-long tradition of providing basic education in Buddhist temples, where boys can ordain as novice monks in exchange for free education, room, and board. Though education has been compulsory and government-run for 100 years, Buddhist temples continue to provide an alternative form of education, especially in rural and poor areas.) Boonman spent the next four years becoming “more unruly and rough.” He got a tattoo—empowered by spells from a Cambodian monk—to act as a talisman that would give him the power to win fights. He was publicly caned after talking back to a monk, and then had salt poured into the wounds. During this time, he also became increasingly interested in spells and witchcraft. “If I took a dislike to anyone, I would take a dead man’s bone and bury it under their house, empowering it by chanting a spell,” Boonman recalls. And all of this he did to solidify his aspiration to become the “village gangster.”

After finishing temple school, Boonman was banished to a remote hut to tend to the family’s water buffaloes. Boonman’s disobedient behavior led to punishment by his uncle, which in turn led to the teenager’s feeling “unwanted.” “I was an orphan and had always felt different from other children, and I wanted to end my life,” Boonman wrote.

The boy stared at a nearby well but chose not to jump in; ultimately he fulfilled his duty to sell the family’s yearly crop of watermelons near the Cambodian border, and then became a temple boy, assistant to elder monks, at Wat Pailom, where his cousin had ordained as a bhikkhu (monk).

“If I took a dislike to anyone, I would take a dead man’s bone and bury it under their house, empowering it by chanting a spell.”

Boonman took to meditation and his studies, and as the rough boy in him gradually disappeared, meditation and learning Pali became the most exciting activities in his world. He learned samatha from the older monks at Wat Pailom, silently saying bu on the in-breath and ddho on the out-breath, the same way he would teach his Western students decades later.

When he was 16, Boonman became a novice monk. His uncle’s family refused to give him permission to ordain, but because of Boonman’s dedication to studying he was sponsored by the abbot.

I was their pride and joy. This ordination was very different to the previous one; the only similarity being that none of my relatives from Ta Prik village came. I became Phra Maha Boonman Poonyathiro, the same name I have used up to this present day.

In order for Boonman to go through the ceremony, his fight-winning tattoo had to go. He complied, removing the tattoo and the last traces of the gangster he had aspired to be.

On the Road

Not long after ordaining, Boonman was accepted to Varanasi Sanskrit University in India and spent the next five years studying for his bachelor’s degree, focusing on the Abhidhamma. His travels were funded by friends and laypeople back at Wat Pailom, and he earned some money by giving Thai visitors tours of Buddhist sites, writing for Thai publications, and offering astrology readings.

On one of his days off, Boonman was visiting Sarnath, the birthplace of the Buddha, when he met a Canadian-born monk named Venerable Ananda Bodhi, who lived at Hampstead Buddhist Vihara in London. (In the late 1960s, Ananda Bodhi would be recognized as a reincarnate lama by the Sixteenth Karmapa, and he later taught around the world as Karma Tenzin Dorje Namgyal Rinpoche.) The two monks were both interested in meditation, and Ananda Bodhi told Boonman to look him up if he ever came to London.

Boonman did have travel on the brain. His studies were finished, and other monks he knew had gone to places like China and Russia. He didn’t know where exactly he wanted to go, but he decided to join an assistant professor in Bangkok, Ajahn Vichian, who planned to travel overland from India to the UK on an English Triumph motorcycle in the summer of 1962 before continuing on to the United States to study. But there was one thing Boonman needed to get sorted out before he left—his passport. Boonman had always traveled on a monk’s passport, which was only valid for passage within India. When he asked at the Thai embassy in New Delhi on a Friday, Boonman was told he would have to return to Thailand to receive permission if he planned to travel as a monk.

“The rest of that day I gave the matter careful consideration; I was now 30 years old and for 15 years I had been ordained as a samanera and then as a monk—half my lifetime. It was a hard decision to make, but I made it. I decided to disrobe and try to live as a layman.” The following day, Boonman bought lay clothes and found a temple where he could perform the necessary ceremony to disrobe.

During the disrobing ceremony one of the candles flickered and almost went out completely, but after a while became bright again. I knew then that my life would meet with a lot of obstacles before it could run smoothly.

Boonman returned on Monday morning to the embassy, where the shocked staff issued him a passport and apologized for having caused him to disrobe.

Soon, the ajahn and the former monk set off on the motorbike with only enough money for food and gas. They slept in police stations or churches to save money and sometimes even slept in the desert. There were the worst of times: being accused of acting as spies in Iraq and totaling the bike when a Turkish army truck forced them off a bridge and into a river. And there were the best of times, like the time when Greek police officers paid for the two travelers’ ferry tickets to Italy after Boonman wrote in their tourist log that he was “proud to be in this land of Plato and Socrates and other famous philosophers.” The two travelers took a train from Rome to London, where the ajahn took a flight to American and Boonman went to the Thai embassy. “The consul was not very happy with my story and decided that I was perfectly good for nothing—a total vagabond who should be sent back to Thailand,” Boonman wrote. His passport was promptly confiscated, but his luck changed when he met an embassy officer whose family supported Wat Pailom, and Boonman was hired as a window cleaner.

Once he was settled—or at least not detained—in England, Boonman reconnected with Ananda Bodhi. It was thanks to him that Boonman started teaching meditation with the English Sangha Trust and moved into the Hampstead Buddhist Vihara, where Ananda Bodhi lived.

At first, Boonman was alarmed at the invitation to teach: he thought of himself as a practitioner—not a teacher, and definitely not a teacher for foreigners. But he accepted, and he organized his sessions differently from those he had at the monastery, with no chanting or taking precepts. Boonman called his method “pure anapanasati,” feeling the sensations of the in- and out-breath. After a few years teaching at the Vihara, he began teaching meditation at Cambridge, where he served as vice-chair of the Cambridge Buddhist Society (the famous Buddhist convert Christmas Humphreys, a British lawyer and judge, was the chair).

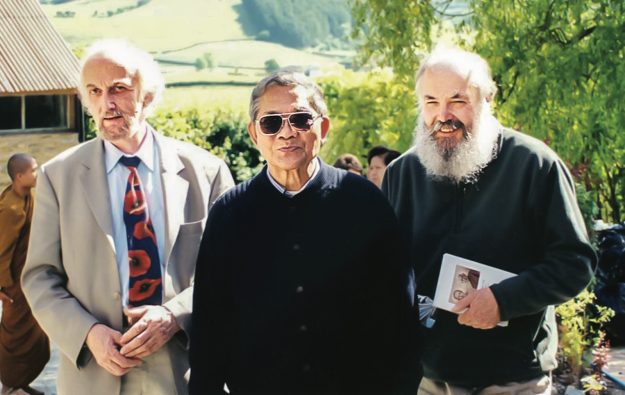

Enter Paul Dennison, then a radio astronomy student at Cambridge. Dennison was familiar with yoga and was drawn to breathing practices that might help his bronchial problems but, as he says himself, he knew nothing about Buddhism. After approaching the Buddhist table at the Society’s fair, Dennison started going to Boonman’s class.

“There was something about the quality of stillness he had that was very tangible,” Dennison answered when asked what he remembered about meeting Boonman for the first time. “And he was just sitting there and waiting for people to arrive, just very, very collected, very calm, but a very strong character.”

Several years later, a Cambridge student of theoretical physics named Peter Betts also found his way to Boonman’s class and attended a life-changing nine-day retreat with him in 1971. Three years later, he moved to Thailand to become a monk. Now, 48 years later, Betts is known as Ajahn Brahmavamso Mahathera—Ajahn Brahm for short.

“He impressed me because his method was simple and it worked for me,” Ajahn Brahm told Tricycle. Today, Ajahn Brahm teaches all around the world and is the abbot of Bodhinyana Monastery and the spiritual director of the Buddhist Society of Western Australia.

Although women could become fully ordained nuns (bhikkhunis) during the Buddha’s lifetime, this tradition died out in Theravada Buddhism nearly a thousand years ago. Among Ajahn Brahm’s many accomplishments was a 2009 ceremony in which he, Ajahn Sujato, and other members of the Theravada bhikkhu sangha ordained four women monastics as bhikkhunis, allowing women equal status and giving them the ability to ordain fellow women monastics. (The mainstream sangha does not share the two monks’ views and does not recognize full ordination for women; both monks were excommunicated from the Wat Pa Pong sangha.)

A Jhana By Any Other Name

Jhanas started becoming problematic in the fifties, when the Thai sangha began favoring the practice of vipassana (insight) meditation over samatha (concentration), which includes jhana practice. Dennison says the jhanas were seen as “superstitious and unscientific,” dangerous, and unnecessary to the development of the Buddhist path. But Boonman continued to teach the jhanas, although, as Dennison and Ajahn Brahm say, he was careful not to refer to them as such.

Dennison explains that Boonman taught meditation the way he was taught to practice. “He wanted to see how it would work with Westerners if he taught the old technique. So he didn’t explain much. He wanted to see what we made of it, basically.”

When asked what might have been the consequences of Boonman disobeying the sangha’s decree, “He probably would have lost his job [at the Thai embassy],” Dennison said. “These old traditions have been taught unbroken for centuries. And Boonman never showed a great deal of bitterness about it.”

The way Dennison tells it, “pure jhana” was not taught in the lay tradition until a few decades later, when Ayya Khema renewed interest in the jhanas as part of what Dennison calls the “new samatha tradition.”

And yet jhana instruction continued, but covertly and by another name.

“Ajahn Chah did teach jhanas, but not publicly,” Ajahn Brahm said in an email. “He would call it appana samadhi, which is the Abhidhamma term. Ajahn Jayasaro, who translated Ajahn Chah’s biography, told me that many old recordings exist of Ajahn Chah teaching appana samadhi.”

Thanissaro Bhikkhu, an American Buddhist monk and scholar in the Thai Forest tradition and the abbot and cofounder of Metta Forest Monastery in southern California, explains that a significant change happened after Phra Phimontham, the abbot of a large monastery in Bangkok, sent students to learn vipassana in Burma in the tradition of Mahasi Sayadaw (1904–1982). (Mahasi Sayadaw’s mindfulness method, the form that spread across the West over the last half-century, did not require jhana practice.) When the monks returned, they were sent to teach in monasteries across Thailand. “These were the people who were denouncing the practice of jhana,” Thanissaro Bhikkhu said.

Over the following years, teachers in the Thai Forest tradition would either reject or embrace jhana, but the anti-jhana sentiment cooled off—in part because Ajahn Lee (1907–1961), one of the most influential meditation masters of the 20th century, “managed to teach one of the strongest opponents of the Forest tradition in that hierarchy how to meditate, and apparently got him into jhana,” as Thanissaro Bhikkhu noted.

While all this was going on, Boonman was teaching the jhanas in the UK, relatively unencumbered and free from sangha politics. When it comes to jhana practice, he “planted the seed,” Dennison writes on the dedication page of Jhana Consciousness.

Dino Daddy and The Future of Jhana

In 1974 Nai Boonman returned to Bangkok with his family, settling into the life of a businessman. His wife’s family ran a jewelry and gem-cutting business, and Boonman became involved with it too. During a recent phone call, Aramsri Poonyathiro, Boonman’s wife, told Tricycle that no one in Bangkok really knows about Boonman’s life as a monk and meditation teacher. Rather, he’s known for his work in the family business and for his tektite collection (tektite is a type of natural glass formed from meteor debris). Boonman owns the world’s largest tektites and also has a collection of petrified dinosaur dung, which in a magazine article earned him the nickname “Dino Daddy.”

A year before Boonman returned to Bangkok, he and Dennison helped found the Samatha Trust (another founding member was the British Buddhist Studies scholar Lance Cousins, 1942–2015).

Boonman returned to England in 1996 when the Samatha Trust celebrated the opening of the first center in Wales (the organization has since opened UK centers in Manchester and Milton Keynes), and until the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic he would make a yearly trip to lead Samatha Trust retreats. In later years he joined these retreats on video calls.

Sarah Shaw, a Buddhist scholar and author, says Boonman has a “slight gift for invisibility.” She describes him as “someone who would have been quite happy to remain behind the scenes for decades. It is difficult to explain—he is not averse to publicity and certainly encourages samatha meditators to write and publicize the form of samatha and breathing mindfulness he teaches. But he is very dedicated to seeing the tradition he teaches thrive.” Shaw added that Boonman is still addressed as Ajahn [a term of respect for senior monks in the Thai Forest tradition] in temples by senior monks who are familiar with him and his work, but he is not a public figure.

This is true in the West as well. Just about every academic and Buddhist teacher not connected to Samatha Trust approached for this article hadn’t heard of him.

Boonman’s daughters run the gem business now, and Aramsri Poonyathiro says that Boonman doesn’t really meditate anymore. Boonman is “rather deaf, and his memory is not great,” Dennison explained in our first email exchange. “He is still very present, however, for those who know him well.”

In 2014, a year after S. N. Goenka’s death, the New York Times ran an article entitled “Overlooked No More: S. N. Goenka, Who Brought Mindfulness to the West.” Boonman is still alive, and still overlooked, perhaps because Samatha Trust never promoted itself, or because he was never the head or spiritual leader of that very democratic organization. The present profile is an attempt to give credit where credit is due.

Correction (8/11): A previous version of this article mistakenly identified Ajahn Chah’s year of death as 1922. Ajahn Chah died in 1992.

Correction (8/30): A previous version of this article mistakenly stated that Ajahn Sumedho was involved in the 2009 bhikkhuni ordination ceremony. It was Ajahn Sujato who participated in the bhikkhuni ordination along with Ajahn Brahm, not Ajahn Sumedho.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.