One Saturday morning, we wandered into the toy section of the Goodwill, and my mother picked something out for me. It was a map of the world, a puzzle, a thousand cardboard pieces inside a paper box for fifty cents. Each piece had a unique shape that fit into another. The point was to find the other pieces that fit into it somewhere in this pile of shapes and lock them together.

When we got home and I sat down to work on the puzzle, she did not pick up a piece or try to help me put it together. Instead, she watched me and what I did. She’d say, “That one doesn’t go there. Try another one.” When one fit, she’d say, “Every piece belongs somewhere, doesn’t it.”

I worked on the puzzle when I came home from school, and piece by piece, I put the colors together. First the blues, which stood for the oceans. Then the reds, greens, oranges, yellows, and pinks of all the many different countries. Weeks later, there were only a handful of pieces left, and when I put in the last piece, I announced, with pride, “Ma, I’m finished!”

My mother peered at the puzzle and pointed at a green spot, said that was where she was from. A tiny country on the lower far right. Then she pointed to where we were at this moment, a large pink area at the top far left. After a moment, she pointed to the puzzle’s edge and then to the floor, where there was nothing. “It’s dangerous there,” she said. “You fall off.”

“No, you don’t,” I said. “The world is round. It’s like a ball.”

But my mother insisted, “That’s not right.”

Still, I continued, “When you get to the edge you just come right back around to the other side.”

“How do you know?” she asked.

“My teacher says. Miss Soo says.”There was a globe on Miss Soo’s desk at school, and whenever she talked about the oceans or the continents or plate tectonics, she would point to those features on it. I didn’t know if what Miss Soo was telling me was true. I hadn’t thought to ask.

“It’s flat,” my mother said, touching the map. “Like this.” Then she swept the puzzle to the floor with her palm. All the connected pieces broke off from each other, the hours lost in a single gesture. “Just because I never went to school doesn’t mean I don’t know things.”

I thought of what my mother knew then. She knew about war, what it felt like to be shot at in the dark, what death looked like up close in your arms, what a bomb could destroy. Those were things I didn’t know about, and it was all right not to know them, living where we did now, in a country where nothing like that happened. There was a lot I did not know.

We were different people, and we understood that then.

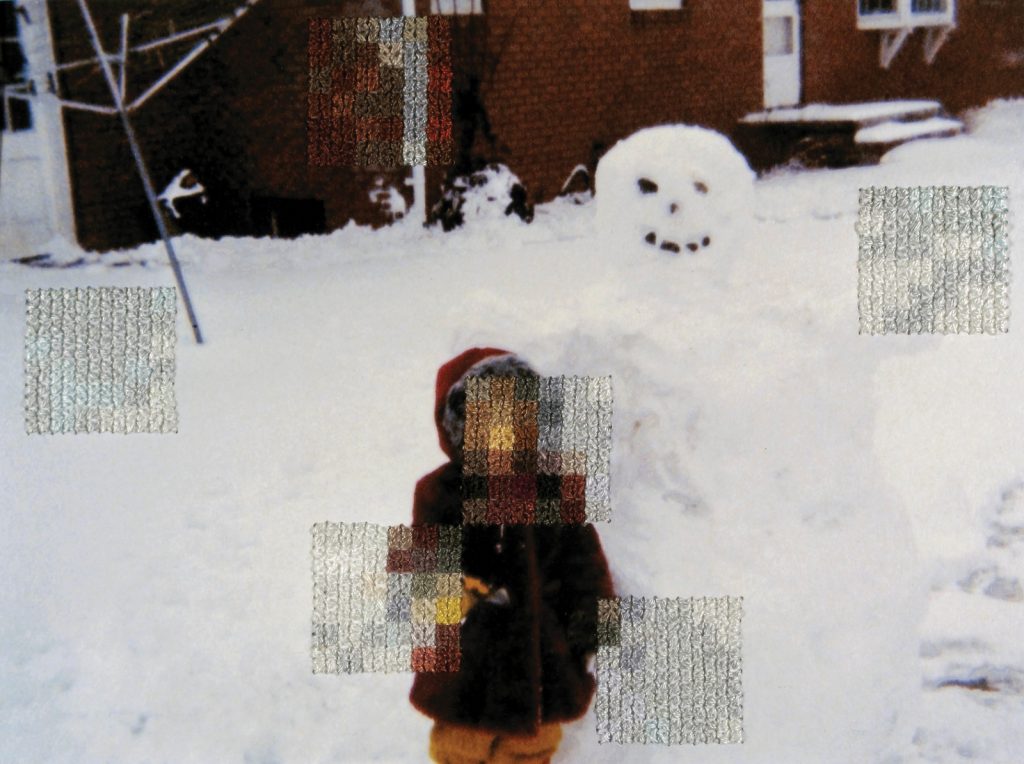

A few weeks after, we went to the park. It was cold and the grass was yellow underneath a lumpy sheet of ice. Earlier, I had been reading and my mother had been watching television. She usually found a show to make her laugh, but that day she couldn’t settle on one. She kept pressing the button on the remote control, flipping to the next channel, and then the next, until she started all over again.

I rushed over to the swings, hopped on the seat of one, and pumped my legs so I shot myself high into the air. My mother sat on a park bench alone, in her blue winter coat, facing me. She was not far. I called to her to pay attention to me, to see how high I was going all by myself, but her head was turned away, her eyes focused on something else.

I stopped swinging and turned to see what she was looking at, the swing slowly coming to a halt. A man had run out of an apartment building in his boxers and a white T-shirt. He seemed flustered, in a hurry, as though he had not planned to be outside in the cold dressed like that.

A woman dressed in a pantsuit had followed him out. Heels tapping on the sidewalk like a pencil on a table.

The man glanced behind him, stopped, and screamed, “It’s over. We’re finished!” When the woman tried to embrace him, he refused, batting away her arms.

I walked over to where my mother was and stood right in front of her, blocking her view of the couple. I said, “Let’s go home.” She looked up at me and there were tears in her eyes. “It’s snowing,” she said and glanced away. She said it once, like that. In a small clear voice. It’s snowing. But the way she said it made it seem like it was not about snow at all. Something that I can’t ever know about her. Then my mother looked up at me again and said, “I never have to worry about you, do I.” I nodded, even though I wasn’t sure if it was really a question.

Soon after, sometime in the night when I was asleep, she walked out the door with a suitcase. My father saw her leave, he told me. And he did nothing.

I don’t think about why she left. It doesn’t matter anymore. What matters is that she did.

All this was years ago, but I can still feel the sadness of that time, waiting for her to come back. I know now what I couldn’t have known then—she wouldn’t just be gone, she’d stay gone. I don’t think about why she left. It doesn’t matter anymore. What matters is that she did. What more is there to think about than that?

Often, I dream of seeing her face, still young like she was then, and although I can’t remember the sound of my mother’s voice, she is always trying to tell me something, her lips wrapped around shapes I can’t hear. The dream might last only a few seconds, but that’s all it takes, really, to undo the time that has passed and has been put between us. I wake from these dreams raw, a child still, though I am forty-five now, and grieve the loss of her again and again.

My father did not grieve. He had done all of this life’s grieving when he became a refugee. To lose your love, to be abandoned by your wife was a thing of luxury even—it meant you were alive.

The other night, I saw an image of the Earth on the evening news. I had seen it many times before, and although my mother was not there, I spoke to her anyway as if she was. “See? It really is round. Now we know for sure.” I said it out loud again, and even though it disappeared, I knew what I said had become a sound in the world.

Afterwards, I went to the bathroom mirror and stared at the back of my mouth. I opened my mouth wide, saw the hot, wet, pink flesh, and the dark center where my voice came out of, and I laughed, loud and wild. The sound went into the air vent, and I imagined people living in the building wondering to themselves where a sound like that came from, what could make a woman laugh like that at this hour of the night.

♦

Excerpted from How to Pronounce Knife by Souvankham Thammavongsa. Copyright © 2020. Reprinted with permission of Little, Brown and Company, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Read more Buddhist short fiction here.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.