From time to time, Tricycle features articles from the Inquiring Mind archive. Inquiring Mind, a Buddhist journal that was in print from 1984 to 2015, has a growing number of articles from its back issues available at www.inquiringmind.com (help Inquiring Mind complete its archive by donating here). Today’s selection is from the Fall 1997 issue, Liberation and the Sacred.

The neck bone’s connected to the head bone, the head bone’s connected to the angel bone, the angel bone’s connected to the god bone. . .

— Jack Kerouac

Lately, I’ve been reflecting on my bones; even focusing mindfulness and meditating on them. This is one part of a general study I have undertaken to try to understand what we inherit from biological evolution and how that knowledge can inform our practice of dharma. The best way to explain this work is to offer you a sample of it, a guided meditation exercise. Give it a try. See if you can feel it in your bones.

This exercise explores the architectural wonder of our body, our vertebrate identity. (If you have a spinal column and limbs branching off it, you are a vertebrate.) To explore the skeletal structure, we will use the body scanning technique, moving conscious awareness through our bones, reflecting on the history and mystery of these highly articulated and animated pieces of clay.

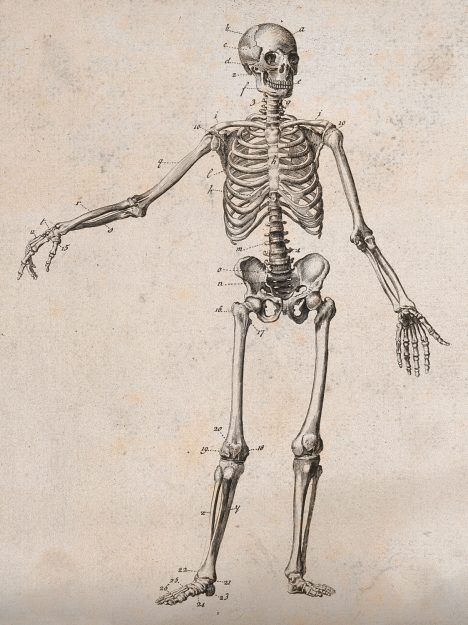

Even if you have some difficulty actually “feeling” the bones, you can still get a sense of their existence and function in this exercise. Let yourself visualize as you scan, if that helps. Follow the image of the human skeleton you have seen countless times in pictures or models. It is a close replica of your own.

The exercise can be done in any posture—seated, standing, or lying down. With your eyes either open or closed, bring your attention to the top of your head. Feel the rounded dome of the skull, sensing its shape.

Next, become aware of the empty spaces in the skull bone—the eye sockets, the jaw, and the cavity of the mouth, the space beneath the ears, and the big opening in the back of the skull where the spine enters.

You can feel all of these openings in the skull as the primary places where messages about the world come through. Isn’t it convenient that the nose, eyes, ears, and mouth are so close to the brain? The rest of the body is still using a cable system—the spine—sending signals up and down the length of us.

Feel or sense the spacious opening at the back of the head where the spine enters. You can experience this space better by moving your head around or from side to side, feeling the muscles that move up from the shoulders and neck to hold all the pieces together.

To really get an inward sense of the bones of the skull, just clench your jaw. Grind your teeth together a little. Another way to feel the skull is to hum out loud, making a nasal sound that vibrates through the acoustic space in the dome of your head.

Open your mouth, feeling the expanse created, and follow this open area back to the cavity of the throat. In the womb, we all develop gill-like structures just beneath our face, and after satisfying the DNA of primitive fish, these develop into jaws, earbones, and larynx.

Come back to your teeth for a minute. Don’t set them on edge, just move them against each other. Feel the power in that finely wrought tool, your mouth. The jaws are perfectly crafted hinges. This tool can bite off vegetables or meat and chew them into a liquid if so directed. Your mouth, in spite of what may come out of it at times, is certainly one of the marvels of nature.

The invention of jaws. . . five hundred million years ago, may have given polychaete worms the advantage over priapulid worms. Hinged jaws were a turning point for armored fish, cartilaginous fish, and bony fish in the seas of the Paleozoic, and for the whole vertebrate evolution that followed, from amphibian to reptiles, birds, and mammals.

— Jonathan Weiner, The Beak of the Finch

The skull inside your head is a refinement of the skull bones of countless other beings, reshaped by their suffering and struggles. Your skull has been growing into this shape for half a billion years, expanding to accommodate a growing brain, slowly forming its narrow, brooding forehead.

Visualize your skull. Recall some of the skulls and pictures of skulls you have seen—from museums, medical texts, Halloween, the Day of the Dead, the Grateful Dead. They are all reasonable facsimiles of the skull you are feeling inside of your own face.

Before moving your attention away from your head, try to feel the entire skull as a single bone. This is your living room, the place where your brain lives. The skull is also holding your face in place. Without it, your head would cave in.

Now continue to move your mindful awareness downward into the bones of your neck, the topmost part of your spine. It is easiest to feel the spine as it rises through the thinness of the neck area. To experience both the flexibility and firmness of these neck bones, try turning your head to the sides or up and down. Again, producing a visual image of the bones may be useful throughout this skeletal scan.

Next, move the scan downward into the spine. Feel the central position of this bone pole, the axis of your body world. By arching your back and head or turning your body to the sides and back again, you can feel the spine’s fine engineering. If you sit up straight or stand and then let all the muscles of your upper body go slack, you will feel the strength of this great ridgepole holding you erect.

Our spine and ribs were born in the ocean as ancient, tubular-shaped marine creatures began to develop both ridges that segmented their body and a flexible spinal rod called a notochord. The structure was a way to protect the innards while still allowing for mobility. Five hundred million years ago these “chordates” gave rise to the first vertebrates, which were primitive fish. (Watch out for the bones!) Later these fish evolved into amphibians which begat reptiles which begat mammals. And we still carry the basic design, head to toes.

After you feel some sense of the spine and rib cage, move your awareness out through your shoulders and into your arm bones. See if you can feel these limbs growing out from the trunk of your spine, the two branches of the arm connected at the elbow. If you can’t exactly feel the bones, just sense their presence. Swing your arms a little, feeling the smoothness of the movement, the precision of the engineering. Shrug the shoulders or flex the elbows, experiencing the hinges, the lever, and the fulcrum. These are the equivalent of fins or wings, once used for locomotion, now mostly for moving the world around—digging, lifting, rearranging the furniture. Sometimes for hugging.

Now move your conscious awareness into your hands, one of the great wonders of natural adaptation. Flex the wrist, move the fingers around, and, finally, wiggle the thumb. The incredible opposable thumb!

Play with this thumb for a few minutes. Press it against each of the other fingers. Then reach out and take hold of your knee or your other arm, or else the rim of the chair or edge of the rug or blanket, using the full leverage of your thumb and four fingers. Then make your thumb immobile, either by folding it into your palm or holding it away from the rest of your hand. Now try to take hold of something without the use of your thumb. It is so much harder to get a grip on things!

The limbs of all vertebrates begin in the womb as fin-like buds. For most mammals, these buds will turn into limbs, and the bone cartilage at the extremities of the limbs will grow five digits. For many animals, such as pigs, chickens, or horses, a few of those digits will disappear by birth.

Of course, we are proud to say that our hands are fully articulated because we have learned so well how to use the opposable thumb. But perhaps we are just now beginning to develop this five-appendage tool. Maybe someday our pinky finger will also become more fully articulated. Then we might be able to do even more things at the same time.

We owe the five fingers on our hands not to novel evolutionary events a million years ago on the African savannahs, but rather as a holdover from the original complement of five digits on the forefoot of the earliest land vertebrates (tetrapods) who evolved some 370 million years ago.

— Lynn Margulis and Dorian Sagan, What Is Life?

Maybe those tetrapods were growing digits just to hold onto land so they wouldn’t slip back into the sea. Hands have since become so dexterous they can build rockets and computers that get us to the moon and back. They can also tie shoes, and some of them can even play the piano.

Take your hand. Maybe it is holding your phone while your other hand is eating a piece of toast or holding a cup, or even counting beads on a rosary or mala. You are ambidextrous. And your wiggly, triple-jointed fingers and extremely flexible wrist are a wonder. It’s taken a half billion years to get your hand into this great shape.

An intelligent octopus would probably regard eight arms as superior.

— Stephen Jay Gould

Move your awareness down into your pelvic bones, feeling their architectural similarity to the shoulders, leading to the limbs of the legs. Move through the two branches of the legs, just as you did with the arms, moving them to feel their solidity, flexibility, and function.

Move down through your ankles and into your toes. Flexing the toes, remember that not so long ago our ancestors held onto branches and vines with those appendages. When you are brachiating around in the treetops, you need to have a good toe hold.

***

You might want to do this vertebrate meditation occasionally or even make it part of a regular meditation routine. My students report that even a few skeletal scans give them a new awareness of their bodies as part of natural processes and a subtle shift in their sense of identity. As the Buddha says in the Samyutta Nikaya, “This body does not belong to you or to anybody else. It is the result of previous activity performed and intended; for now, it should be felt.” It is no trivial matter to experience the bare bones of your being.

♦

Related Inquiring Mind articles on body mindfulness:

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.