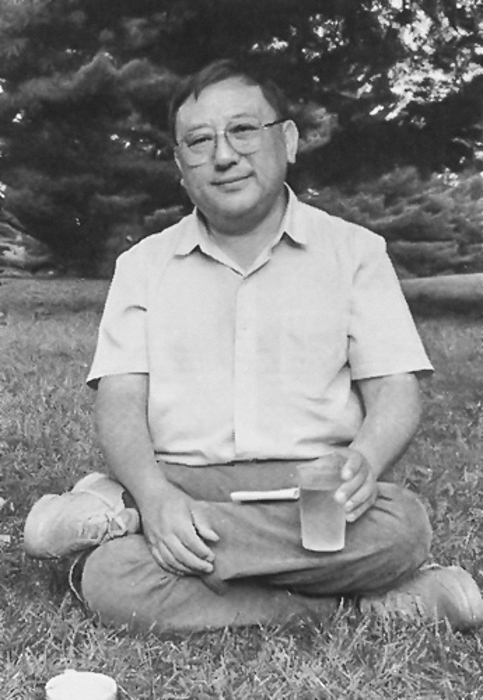

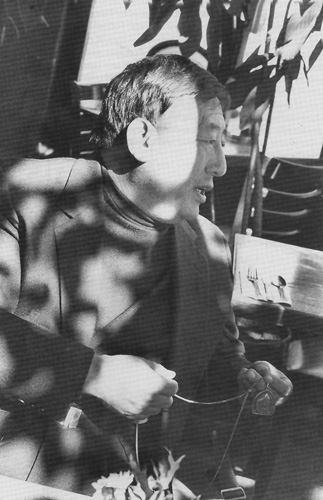

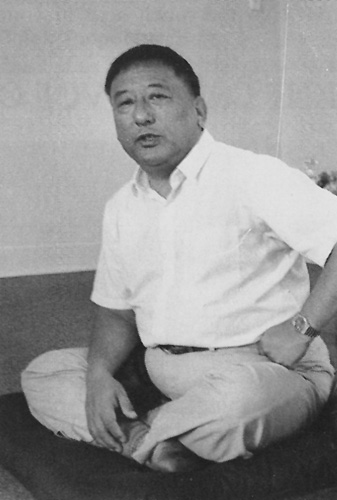

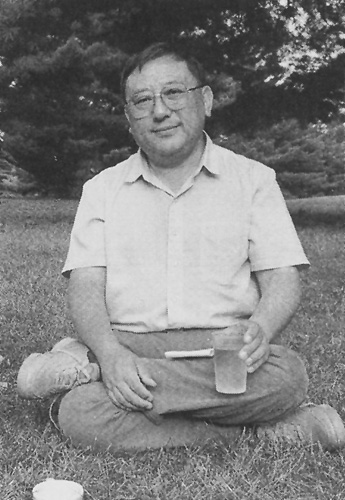

Gelek Rinpoche, a lama trained in the Gelugpa tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, is the spiritual director of the Jewel Heart Tibetan Cultural Institute and Buddhist Center in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Identified as a lama before the age of five, he began his training in Central Tibet, where he studied with a hermit teacher, and later joined Drepung Loseling Monastery, where he remained for fourteen years. In 1959, amid political unrest, Gelek Rinpoche, then twenty, escaped to India.

Since settling in the United States in the late 1980s he has been traveling and teaching regularly at centers in New York, Chicago, Cleveland, and Lincoln, Nebraska, as well as in the Netherlands, Southeast Asia, Canada, Mexico, and Brazil. He became a citizen of the United States in July. This interview was conducted for Tricycle by Helen Tworkov in Ann Arbor.

Tricycle: Your own tradition is the Gelugpa school of Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhism. How would you define Vajrayana?

Gelek Rinpoche: The purpose of Buddhism is to cut down anger, hatred, and jealousy. The way you do it is very simple. If you cannot handle an attachment, then you completely cut out whatever helps the attachment grow. It comes down to discipline. Theravadin teachings encourage a very strict discipline. The Mahayana approach is slightly different. You make use of your attachment in order to benefit others. In the Mahayana, attachment can be a useful tool for a bodhisattva.

Tricycle: Can you give a specific example of that?

Gelek Rinpoche: Bodhisattvas, for instance, use love and compassion. They also use attachment itself to build close relationships that can lead people to the path. The bodhisattva may use some of those attachments to help others. In Vajrayana the most important technique is transformation. Instead of cutting something like attachment out, you transform it. Instead of the difficult, disciplined way of pushing something down, suppressing it, cutting it out—instead, you work with that, play with that, and then try to transform it. Tantras use attachment as a path, as a method.

The second most important technique in the Vajrayana is visualization. We have five skandhas, or the five aggregates [form, sensation, perception, mental formations, consciousness]. The essence of the Vajrayana is to transform these five aggregates into five wisdoms through visualizations and other techniques. We play with our emotions and work with them. It is a very quick path. In the Theravadin tradition the goal is the arhant level, total freedom from pain, sufferings, and delusions. The goal in the Mahayana tradition is the buddha state, or buddhahood, which is the one state beyond the arhant level—but it takes aeons to reach. And in the Vajrayana, the goal is Buddhahood, which is considered reachable within your lifetime, whatever short amount of life you have left. So Vajrayana is a very quick path and a very sharp, dangerous path. If you do not know how to handle it, then you have a problem. It’s like catching a snake. If you know how to do it, there’s no problem. If you don’t know how, it will bite you.

Tricycle: Why is it dangerous?

Gelek Rinpoche: You play with emotions and you play with negative emotions, like attachment and anger, and you try to transform them. If you do not know what to do with it, you will lose your power, and the emotions will take over.

Tricycle: So there’s a chance in the practice that you can exaggerate anger for the purpose of working with it, but then if you can’t transform it, you have more anger?

Gelek Rinpoche: That’s right. Also arrogance. A lot of Buddhist practitioners—quite a number of them—are very arrogant.

Tricycle: Is there something in the practice itself that accounts for that?

Gelek Rinpoche: When you meditate on love and compassion, in the Mahayana tradition, you sit and close your eyes. You visualize that you are the most important person and all the sentient beings are nameless, faceless dots that we meditate on: we are giving them love, compassion, and we are purifying them, making them perfect. These sorts of mental exercises are all done with nameless, faceless dots. One day the dots have a name and a face. You freak out! You say, “Oh, you’re not supposed to say that. You’re supposed to go do whatever I told you to.” So that is where arrogance comes in, in my opinion.

Tricycle: So when you’re just sitting quietly, meditating on love and kindness, your sense of self-importance grows?

Gelek Rinpoche: Yes. Without realizing it, you feed your sense of self, your ego. Then a person loses humility, which is a very important Buddhist quality. For example, look at His Holiness the Dalai Lama. He might have lost his country, but he’s still the Dalai Lama. But how humble he is. We lose humility because we feed our ego by being the lord of the universe, feeding everyone with love and compassion. That is a problem. I always emphasize meditating on compassion for a living person, your family, persons you care for, and then expanding on that.

Tricycle: How old were you when you were recognized as an incarnate lama?

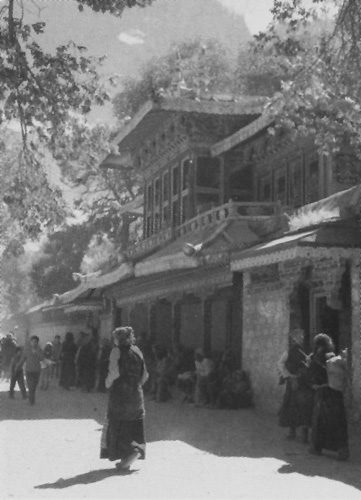

Gelek Rinpoche: I was about four. I found a place as a reincarnation of one of the abbots of the Gyuto Monastery. Then I went to Drepung, one of the largest monasteries in Tibet, in central Lhasa, which had 13,000 monks. I also had a great teacher who was a hermit who lived in retreat about 3 or 4 miles from the monastery. First I was put with him—on one condition. He said he would keep me if I were left alone. No attendant, nothing. My father said, “That’s great.”

Tricycle: What did he teach you first?

Gelek Rinpoche: He taught me to memorize and then to meditate. I was put with his senior students, and I used to look around and repeat what I saw. He used to tell me that the life I had was extremely important, very precious, and he told me to think about it. He said, If you think it is not important, tell me, and if you think it is important, tell me why. He was so kind, and at the same time he said, You should not be spoiled. He used to let me sleep on the floor sometimes, and sometimes he sent me out in the valley to dig up the roots of some berries, put them in water, take them outside and put them in the sun, and then take them back in the evening. That was my tea.

Tricycle: How long did you live with him?

Gelek Rinpoche: A very short period, not even a year. I joined the monastery and then lived with him again for a couple of years when I was seven or eight. After that I was sent back to the monastery to do normal Buddhist studies for fourteen years.

Tricycle: In the west we don’t have any real sense of “training” children.

Gelek Rinpoche: Well, the Tibetan way of training kids is not always great. Normally, kids in the monastery are just dumped with the others. If you can pick up things, you pick them up. If you don’t, you don’t. As an incarnate lama it’s different—you have special tutors who teach you to memorize the texts and the prayers. After memorization, they send you to the commentary teachers. I had one teacher for reading, one for memorizing, and one for debate. When they teach debate, they train you to find certain points where you can state your theory, your viewpoint. They train you to protect your theory against other views and logics, and if you cannot protect it, you know you’re wrong and you have to surrender. You argue in the loudest voice possible, clapping your hands and thumping your feet. You keep on debating until you are proved to be wrong or proved to be right. If you are proved right, then you begin to understand that is what Buddha’s message is, and then, finally, if you are convinced, you meditate on it and adopt it as part of your life. That’s how the essence of Buddhism becomes a habitual pattern.

Tricycle: How do you remember those years in the monastery?

Gelek Rinpoche: It was the best time of my life. No question.

Tricycle: You left when you were twenty?

Gelek Rinpoche: Yes, I left in ’59 during the trouble between the Tibetan government and the Chinese. The old atmosphere of learning and meditation was actually lost before ’59. The monastery was already contaminated with political views and taking sides. Even among the abbots—some were pro-communist and some were anti-communist, or pro-Chinese or anti-Chinese. Also among the incarnate lamas and the monks, some were pro, some anti. In early March of ’59 there was word that the Dalai Lama was going to be invited by the Chinese to their military headquarters and that they told him: “Do not bring the bodyguards or weapons.” In the middle of the night people went around Lhasa, knocking at doors, saying that the Dalai Lama was going to be taken away by the Chinese soldiers. As a result, early in the morning everybody rushed to the summer palace to beg the Dalai Lama not to respond to the Chinese invitation. During that period there was one cabinet minister who was also commander-in-chief of the liberation army. He came by jeep to the palace. He was stoned by the people there.

Tricycle: Why?

Gelek Rinpoche: They thought he was a Chinese agent. And a monk official went to the meeting of the officials that they had every morning, a sort of ceremonial get-together. He went in the morning with his monk’s robe on and came back later in the evening on a motorcycle, wearing Chinese jeans. People took him for a Chinese agent. They stoned him to death and dragged his body to the market area. Thereafter tension developed and it was terrible. One night, about 3:00 A.M., I woke up to the sound of cannons firing and machine guns going. Nobody knew what to do. All the monks went up on the roof, and by early afternoon we saw people and horses coming out of the Norbulingka summer palace rushing toward the river. Then a cannon went off, and we thought everybody was killed. After the dust settled we could see the people again. Then everybody went to look for a place to hide because we knew they were going to hit the monastery. I started walking toward the mountains, but the Chinese had some kind of a flare shooting into the air so that even in the mountains you can see your own shadow. We were scared to go, but we went anyway. We hid behind rocks and started counting the intervals in between flashes, so there was a “One, two, three” count and then we crossed and hid in the next crevice, or covered area. That’s how I gradually came to India.

Tricycle: And then?

Gelek Rinpoche: I was a dharma teacher in the Tibetan nursery school in Simla, run by the Save the Children Fund in London, headed by Lady Alexandra Metcalfe, daughter of the Viceroy of India.

Tricycle: Many people have commented on how much your English speaking style is similar to that of the late Trungpa Rinpoche. Apparently you both learned English from the same woman. Was that Lady Metcalfe?

Gelek Rinpoche: No, that was Frieda Bedi. She was a British woman who stayed in India after independence and was a very close friend of Nehru. She married a Punjabi called Bedi. Mrs. Bedi came in contact with me in Buxador, a camp where the monks were staying, which used to be the British prison for those working for independence. They’d been locked in that camp and we were put there, but it was used as a refugee camp, not a prison camp. Mrs. Bedi visited all the refugee camps. She was interested in Tibet and adopted two young incarnate lamas and invited them to stay at her house in Delhi. One of them happened to be Trungpa Rinpoche and the other happened to be me. So that’s the connection with Mrs. Bedi. Mrs. Bedi later became a Buddhist nun with the Karmapa and was called Sister Palmo.

Tricycle: And were you still a monk at that point?

Gelek Rinpoche: Yes, I was a monk at that time, but soon after I rebelled against my upbringing and picked up drinking, cigarette smoking, and…

Tricycle: Women?

Gelek Rinpoche: Yes. I was wondering all the time how sex with a woman would be. I wanted to experiment. Also, if you are not wearing a robe, you can talk freely with laypeople. I like to talk about everything. If you are a monk, there’s always some kind of a gap there. That was always one consideration. Sex was another. On the other hand, I wondered what my teachers would think, what His Holiness would think, and how I was going to face them. That was the battle in my mind.

Tricycle: So then you started to lead a wild life?

Gelek Rinpoche: I was looking for some kind of very big kick, which I did not find at all—not in cigarettes, not in marijuana, not in alcohol, and not so much in sex either.

Tricycle: The fantasies made it a little overrated?

Gelek Rinpoche: The fantasies were very much overrated. And then gradually all the Rinpoches said, Well, it’s unfortunate, but it is nothing unusual. A lot of people go through that. They kept on telling me that even though I gave up my monk vow, I was still a rinpoche. They told me to remember that I was within dharma.

Tricycle: You weren’t tempted to go back to being a monk?

Gelek Rinpoche: No. I’ve received a lot of appeals from different monasteries and abbots, but I’m happy as I am. I can talk to people as a lay person, and can talk to them about their family problems, sexual problems, and companion problems. And I had a long, nice holiday. The Rinpoches let me be wild for a while, and it was a big disappointment. There are big fantasies of nightclubs, drinking, smoking cigarettes, having sex, but all of that really did not give me anything at all. As a matter of fact, it gave me more problems, more headaches. Gradually, I came back totally to dharma.

Tricycle: How did you get to Ann Arbor?

Gelek Rinpoche: In 1980 two friends from Ann Arbor came to India and studied with me and invited me to visit. I really liked this area. You know one of the reasons I liked it here the most? The four seasons. In Tibet there are four seasons, but in India they don’t have four seasons.

Tricycle: What was your thinking about coming to America?

Gelek Rinpoche: For one thing, the transmission of the dharma is very important. Dharma does not belong to Tibet or Tibetans, dharma belongs to everybody. The West, in particular, is in need of dharma because of the lifestyle, the pressure, the difficulties. Many people had put in a lot of effort here—Trungpa Rinpoche, Lama Yeshe, and the late Karmapa and Kalu Rinpoche—but unless you stay here constantly, and become a part of people’s lives, and understand their culture and family relations, it’s difficult to contribute to rooting the dharma here. I also had an opportunity to work on a Tibetan history book by Melvyn Goldstein [The History of Modern Tibet 1913-1950, University of California Press], so I came and helped him.

Tricycle: A lot of Western Tibetan students attacked that book. They said it was pro-Chinese.

Gelek Rinpoche: Well, we interviewed a number of Tibetans who were in Tibet at the time of the Chinese takeover. The way Goldstein works is very interesting. Take an example such as when the Thirteenth Dalai Lama passed away. We went to the people who were in the monasteries at that time and asked them how they came to know about his death and what they felt. Then we spoke with the noble families, the government officials, and asked how they came to know, what they did, what they felt. Then we spoke with the soldiers, sergeants and ordinary soldiers. Then we spoke with people in the villages near Lhasa and then to the Khampas in Eastern Tibet and asked them how they came to know, how long it took, and what they thought about it. Then we spoke with the nomads. So we interviewed all these people and the shocking surprise was that the villagers in East Tibet did not know about his death for three months. Even the villages in Lhasa didn’t know for months. The monasteries knew immediately, and the noble families knew immediately. This is just one example.

Tricycle: What are the implications of this?

Gelek Rinpoche: Well, the message didn’t get through. It shows how weak communication was in Tibet. What can be more important than the passing away of a Dalai Lama?

Tricycle: So the government is out of touch with the people.

Gelek Rinpoche: That’s right. And every single point, every single instant is experienced totally differently by all of the different people involved—not because of their memory, but because of their environment. The soldiers, the monks, the lay officers, and the religious all have a different view.

Tricycle: Were you surprised by the response to the Goldstein book?

Gelek Rinpoche: No. It was controversial.

Tricycle: Many of the Western dharma students familiar with the history of Tibet seem to think that there is a skillful means in maintaining an idealized picture of Tibet because it serves the “Free Tibet” movement.

Gelek Rinpoche: My view is that history is history. I don’t even think His Holiness would keep a romantic view of the old Tibetan system. You have to give as honest a picture as possible. Whole countries, whole worlds distort their histories. I interviewed people to make an honest statement, a simple statement of what happened. I didn’t interpret the interviews, or draw conclusions. I’m not the author.

Tricycle: What is your hope for Tibet today?

Gelek Rinpoche: I see videos and photographs of a lot of young Tibetans doing nothing in Lhasa, just idly sitting, drinking, gambling, and that is how they spend their life. When I look at them carefully, I think none of them has received proper education. Tibetans don’t like the Chinese education that is coming through the schools, and those who do study can’t pass the exams because they’re not in Tibetan, they’re in Chinese. And yet, at the same time, all Chinese can move to Tibet and make their living. So what is going to happen in the long run is that the Tibetans won’t be able to earn their living in their own country.

And the schools do not teach Tibetan language because the local authorities are not encouraging them. Although there is vocational training set up by the Chinese, it is totally for the Chinese. I would like to set up a vocational training school for Tibetans. I am not trying to produce great educated scholars, but some way for the Tibetans to earn their living. That is something which, from a humanitarian point of view, we can do and should do. l am hoping to visit Tibet next year. Hopefully, by that time we will be able to begin something over there.

There is no Tibetan who does not want a free Tibet. But at the same time, there has already been thirty years of Chinese occupation, and if this continues Tibetans will not be able to earn their living in Tibet—even under their own system. At least that much we can change. We can also keep the language and culture alive. If they could learn plumbing or electrical systems as well their own language and culture, it would be a great gift to Tibet.

Tricycle: Dharma seems to pervade so much of Tibetan culture, but it did not seem to be able to counter the same old bureaucratic and political greed in the authorities that we see all over the world. In the West, we are so idealistic and we like to think that the dharma coming here is a chance to put it together. Maybe it never can be put together.

Gelek Rinpoche: Well, there is a very pervasive dharma in Tibet. Within the culture, within the family, the family tradition—everything. Basically, the old Tibetans have a very kind nature, something more than just natural Buddha-nature. There is a kindness and gentleness that you can see in their faces, in their eyes, and in their minds. However, the political intrigue and corruption and economic exploitation are also there. The image of good old Tibet—everyone living in love and compassion with a flower in their hand—I don’t think was true. On the other hand, the majority of the people have nothing to do with intrigues, politics, or power struggles. And the majority of the monks have nothing to do with the monastery power structure or struggle. The dharma remains with the individual. Dharma influences culture but remains within the individual. I don’t Iike the old society, the old way of functioning, or the old government, which is very much a feudal system. I have a lot of young Tibetan friends today who don’t like me to say that, but the truth is that it was a feudal system.

Tricycle: How do you see dharma unfolding in the West?

Gelek Rinpoche: It is coming out of the monastery and getting into the lay society. I think it is going to take root within individuals.

Tricycle: Do you see it creating an enlightened society?

Gelek Rinpoche: Who knows? It is possible, but that may take hundreds and hundreds of years. You cannot romanticize it. It is going to happen gradually within the individual, the tremendous improvement of the individual. Political intrigues will continue, war will continue, and killings will continue. But at the same time there will be the improvement of the individual.

Tricycle: Is the acculturation of Buddhism a natural process?

Gelek Rinpoche: Well, Buddhism must remain a practice of the individual rather than the institution. Institutionalizing the Buddha can be devastating.

Tricycle: Is that what happened in Tibet?

Gelek Rinpoche: Sure. There was corruption because monasteries became so rich and big and powerful that economic corruption came in, and then political corruption came in. When Buddhism becomes a state religion, corruptions come along with it. It is human nature.

Tricycle: We in the West are very hopeful about this integration of the inside and the outside, the political and the secular. How can we best work to help society as a whole without institutionalizing the dharma?

Gelek Rinpoche: In the great period of the Buddhist golden age, Buddhism was not institutionalized.

Tricycle: But in addition to all the corruption and problems, we think that Tibet did create this extraordinary body of knowledge, and very intense dharma activity was generated by big monasteries, by thousands of lamas. So maybe if you don’t have institutionalization, you don’t have such powerful dharma either.

Gelek Rinpoche: Well, you know what the Tibetans used to say: “The great monastery is like the great ocean. There are a lot of great things and a lot of bad things, too.” What we are experiencing today is not necessarily the product of the great organized institution. Good institutions have a tremendous amount of knowledge to contribute, but what we are really experiencing is the efforts of individual practitioners and the efforts of the Tibetan lamas who have done their practice for thousands of years, lamas who learned in institutions but who practiced individually.

Tricycle: Can the monastic training of your childhood be transmitted to adult secular Americans?

Gelek Rinpoche: Yes, definitely. I don’t think that you have to become a monk. The essence of dharma lies within the people. In the tradition it is said that the root of dharma lies in the sangha of celibate monks and nuns, but if you think carefully, laypeople—men and women and children—are capable of maintaining and contributing to that. The translation of Buddhism to the West is going to be through laypeople. When dharma was transmitted to Tibet, it was not in a monastic form alone. Marpa, the founder of the Kagyu tradition, was not a monk.

Tricycle: What do you think the benefit of monasticism is?

Gelek Rinpoche: Atmosphere and opportunity. But if you do not become a monk, that does not mean that you don’t have opportunity.

What does Buddhism really mean? To me, Buddhism means to correct negativity. In order to achieve that, you watch your mind. Nobody wants to kill anybody. We create negativities mostly by being unaware. Dharma practice means to change your habitual patterns and change your addictions. The monastery contributes to that because they make it a discipline. There is somebody watching over you. That helps. Also individually, if you have the vow of what we call self-liberation you naturally protect that vow, so you automatically change your habitual patterns and get over your addictions. That is why monks and nuns have more environmental support. But the real purpose of Buddhist practice is to cut down your addictions and to correct your habitual patterns and this can be achieved as a layperson or as a monk or nun. That brings us to the question of Buddhist ethics—changing habitual patterns and getting rid of the old addictions, such as attachments, and replacing them with love, compassion, generosity, and patience.

Tricycle: Do you mean using the precepts to alter one’s habits?

Gelek Rinpoche: No. The problem, when you talk about the Buddhist ethics, even in the West, is that the moment you use the word “ethics,” people start thinking about morality and vows and all the different disciplines. In my opinion, Buddhist ethics are based on the Four Noble Truths. In Uta Tantra Maitreya Buddha compares the Four Noble Truths with illness, the cause of illness, the medication, and the healing, which is the perfect balance of the elements.

Tricycle: How does this compare with the conventional version of the First Noble Truth: “Life is suffering”?

Gelek Rinpoche: There is a lot of joy. We enjoy life. We enjoy having sex. We enjoy having a drink. We enjoy having a good holiday. Don’t we? A better translation would be “the truth of suffering.” It is not really suffering as suffering, but truth of suffering because we cannot proceed when we do not properly acknowledge the sufferings that we have. But we also have to acknowledge the joy that we have. If people think that Buddhism is “life is suffering,” then they think they have to feel bad if what they’re experiencing isn’t suffering. There is a joy within life that you have to accept. But even in those joys there is natural suffering too. That is the First Noble Truth. The truth of suffering.

Tricycle: What does that mean to individual practitioners?

Gelek Rinpoche: We carry addictions. The first step is acknowledging that. The acknowledgment itself is the purpose of the First Noble Truth. If you really look at the Buddhist tradition, the First Noble Truth is to understand the truth of suffering, which means acknowledge the problems we face, the addictions we have. If drinking coffee makes you sick, you have to cut the coffee out—and likewise when you recognize the addictions of attachment, anger, hatred. The Second Noble Truth is to find out what it is that causes these addictions and then to separate yourself from it. There are many causes of suffering created by individual karma—anger, hatred, jealousy, and, above all, ignorance. Ignorance is the most important one, the one which really creates all other negative emotions, such as anger, attachment, hatred.

The Third Truth is cessation of ignorance. And the Fourth Truth is the Path, which is the medicine. If you have too much acid in your stomach, you take Pepto-Bismol. The practice, the path, is the antidote to whatever your problem is. If you’re too angry, you deal with the passions. If it’s laziness, you deal with diligence. If it’s ignorance, you use wisdom. If you’re wandering or thinking too much, you use meditation. These are the methods that automatically bring us to Buddhist ethics.

Tricycle: Getting back to monasticism, didn’t the strength of the teachings in Tibetan society keep coming from the monastery and going out into the lay society?

Gelek Rinpoche: Yes.

Tricycle: So if we don’t have the monastics to inspire or to keep cooking the teachings within the monasteries, what are we going to end up with?

Gelek Rinpoche: With nothing. But from generation to generation we keep on losing it. My generation, for example, can never compare with the earlier masters.

Tricycle: So from the time of the historical Buddha until now, it is one long degeneration?

Gelek Rinpoche: Yes, definitely. That is why it is called “the degenerate age.” In rare cases one or two great people may come up, but you always look back on the lineage masters, at what great qualities they had. How they practiced, which always gets watered down. This is historical fact. In Tibetan Buddhism, earlier masters are so great that contemporary masters cannot ever think of putting their feet in their shoes. We are following in their footsteps, but we cannot fill their shoes.

Tricycle: Is part of your own optimism about Buddhism in America related to your acceptance of inevitable degeneration?

Gelek Rinpoche: I think that is a weak way of looking at it. I am optimistic because most Americans interested in Buddhism are very intelligent and their minds are open and sharp, which helps them understand, analyze, and do things. With that in mind I am very optimistic.

Tricycle: But you are not anticipating a great flowering of dharma that will in any way shift the propensity of degeneration?

Gelek Rinpoche: I do pray for it.

Tricycle: You have referred to the Buddhist path as a process of replacing our addiction with generosity, compassion, and wisdom. The implication is that we have these addictions which are not “inherent” but which we feel to be “inherent.” And yet in the Buddhist teachings, and in Tibetan Buddhism in particular, there’s an emphasis on natural loving-kindness. Where does this natural loving-kindness come from?

Gelek Rinpoche: The individual has Buddha-nature, which is good nature. Whether or not that is loving-kindness, I’m not sure. Buddha-nature has two natures: static and growing. The growing nature builds up love and compassion. There is no single human being who does not have a good quality within them, but we don’t all develop our qualities. We don’t encounter each other with these good qualities; instead we put cold shoulders toward each other because of our addictions.

Tricycle: There’s a difference in understanding Buddha-nature as essential emptiness and understanding it as loving-kindness. If we have no inherent addiction, why do we inherently have a loving nature?

Gelek Rinpoche: Buddha-nature is, of course, emptiness. But I don’t think emptiness is Buddha-nature. If you take Buddha-nature and ask, Is this emptiness?—it is emptiness. But emptiness is not Buddha-nature. There is something called “I” who comes from a previous life, who lives in this life, who will go on to a future life—I do have that. Is that inherent existence? No. Trungpa Rinpoche calls this a “continuation of a discontinuity.” It is changing every minute. However, there is something that is continuous. It is like an ice cube on top of another ice cube; there is some kind of link, some kind of continuation of water which can join them together or can be separated. That sort of continuation is there, and that very continuation is the “I” who comes from a previous life. I live here, I will go, and that carries Buddha-nature in it. If a journalist shows a picture of children suffering somewhere—in Kuwait, or Somalia—people say we must do something. That generous reaction is because of the good nature there. That feeling comes from the compassion that everybody has. But kindness and love is something that you can build on. You have a seed within that to grow.

Tricycle: Is it possible to understand cultures and societies in terms of karma and reincarnation?

Gelek Rinpoche: There is collective karma. I’m not sure what that does with culture. People create collectively, experience collectively, so we call that collective karma. But the addictions, and the development, all of them are within the individual.

Tricycle: Is there a way of understanding what’s happening to Tibet in terms of karma?

Gelek Rinpoche: Sure. I think of those of us Tibetans who are suffering today. I’m sure that it’s something earlier, some terrible action against whomever it might be, not necessarily against the Chinese. I don’t know if we have destroyed somebody’s homeland or what we have done collectively, but that is what we are experiencing collectively today. This is a collective karma. Tibetans are experiencing this suffering. This is definitely karma, no question.

Tricycle: Well, when we talk about the future of dharma, we make a certain assumption about the future—that there will be a future for the planet. What do you think will happen to this planet?

Gelek Rinpoche: I don’t think that the world will end in one big bang. I think that it will end gradually, piece by piece. Region by region there will be more difficulties.

Tricycle: How bad will it get?

Gelek Rinpoche: Very bad. It will take a long time.

Tricycle: Will the planet as we know it survive?

Gelek Rinpoche: One day it will go. One day the planet will retire. I hope we don’t see it. I hope our children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren don’t see it.

Tricycle: But it can happen?

Gelek Rinpoche: Can happen and will happen. But very slowly.

Tricycle: And there is no way to reverse that?

Gelek Rinpoche: I don’t think a total reversal is possible, but we will go back and forth for a long time. It depends on people. We all must work and try to serve it for as long as possible, but forever is not possible. After all, it is impermanent and must end.

Tricycle: If the planet disappears, what does it mean about our own karma?

Gelek Rinpoche: We will be born on another planet. This is not the only planet in existence.

Tricycle: When we talk about dharma, we are not limited in terms of the human realm?

Gelek Rinpoche: No, definitely not.

Tricycle: Your mind doesn’t stop anywhere along the way of imagining the disintegration from the human to nonhuman? Earth to another planet?

Gelek Rinpoche: No problem at all for me.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.