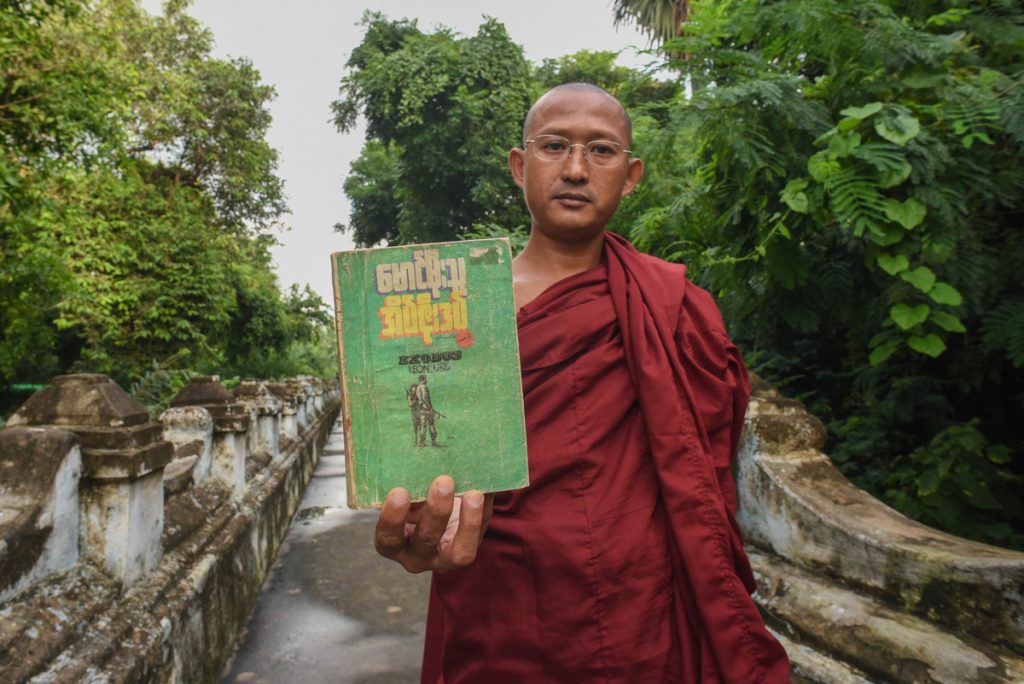

Ashin Dhamma Nanda, 41, lives in Mandalay and has been collecting books since he was 16 years old. It’s his passion and his main activity outside of the monkhood. Yangon-based journalist Joe Freeman interviewed him at his monastery with the help of Aung Naing Soe, a Burmese journalist and translator. This is his story, in his own words, edited for length and clarity.

I have around 10,000 books.

I was able to keep these books because I’m a monk. If I had been an ordinary person, the previous government would have defeated me. I was lucky.

My mom and dad broke up when I was 9. We used to be very rich. Then they split their business up. I went to a monastery when I was 10. I had relatives in town but they didn’t take care of me. The person who becomes poor after being rich does not have many people to talk to.

Books became my friends. It’s simple. You never forget your childhood friends no matter how old you get because they were good to you. Books were my childhood friends and also my first love. If you are tired and not reading books, they aren’t going to curse at you. They will never complain. No friends will be better than these. The one who loves literature is the same as the one who is addicted to heroin. It’s so easy to be addicted.

When I was 13, I arrived at a monastery in the town where I was studying. At the time, I read books from the Ni Wah & Nandi Library in the monastery, which was established by two monks named U Ni Wah Ya and U Nandi Yah. Once, U Nandi Yah told me that I should collect books and distribute them as it can bring merit. I decided to open a library when I got older. But I had no money and I had to save a lot.

I’ve collected books since I was 16 years old. I moved here [to Mandalay] from Labutta [in the country’s southwestern delta region] when I was 21 years old. I came here to learn Buddhism. It took me eight years to pass the senior class because I was building the library and studying at the same time.

I collect novels, mostly, since they give us a delicate soul and also support a sense of belonging. The man who reads novels already knows history or poetry. You don’t need to push him to read. Most people who read novels have a delicate soul and they can distinguish between truth and falsehood.

It’s quite strange for me that the novel Clouds in the Sky by Ko Mya Aye has made me weep twice. I tested it on others. I gave the book to some tough guys and they came back and told me “What kind of book is this? It makes me cry!” This is so nice. I collect by reference; for example, when someone talks about a novel or its plot or describes the name of another book I go and look for it. Books refer to other books. I read a lot but the books that stay in my mind are The Haj and Exodus by Leon Uris. I know John Steinbeck and Margaret Mitchell, who wrote Gone with the Wind. I feel close to them even though I don’t understand English.

My library became well-known around 2003. I had special methods for donations. It wasn’t going to be a burden to readers. Let’s say you had two lakhs [$180] per paycheck, I would ask for about 2,000 kyats [$1.70) at the end of the month. If you didn’t have money, I never mentioned donations. For example, [a man named] Maung Phyu had a paycheck of three lakhs and he drank beer almost every night. I would tell him not to drink beer for one day and ask for a donation of 3,000 kyats ($2.50). And I also received small amounts of money from my supporters for betel nut or tea. If I got 10,000 kyats from them, I spent 7,000 kyats on books. With the remaining 3,000 kyats I would drink tea and treat my visitors to tea. That’s all. I’m loyal to this. Money doesn’t come from the sky.

Once I was threatened and told that I had to register my library. It was during the military regime. They wanted to get a list of books and they would check people who came to the library. Their plan was to donate their propaganda books and ask us to read them. I had to keep important books secure. Most of the books I secretly kept belonged to the “red” group, which were mostly about revolution and leftist causes. I didn’t dare lend these books because there were some informers. When the political situation eased, those who threatened me came and asked me to donate books because they’re going to open a library. It’s so funny. I didn’t donate to them.

My library was open at the Shwe Layone Monastery in Pyaygyi Takhun Township from 2000 to 2013. The head monk of that monastery thought I would take [over] his monastery when he passed away. He wanted to hand it over to one of his pupils. I didn’t have a plan to take it, but he asked me to find another place for my books [anyway]. So I moved to this monastery [Pyay Kyaung] instead. I’m friends with the head monk here. Now I just need a building for my library. I have kept my books at this monastery since 2013. It’s like my books are in prison. Even though I can’t reopen my library, I have been able to exhibit my books. I discovered these books so I am trying to preserve them. I will never give up.

Sometimes I think about what would happen if I get sick. I have to think about it because I am over 40 years old. I have to leave everything behind when I die. No one is going to burn my books at my funeral. I can’t leave my books behind carelessly. Some have suggested that I should work as a preacher or a writer. But I don’t want to. Have you ever seen a writer establish a library? The life of a librarian is different from that of a writer. I posted this on my Facebook page: “Don’t make friends with writers. Just make friends with books. If you are friends with a writer, you have to read all the books he has published even if you don’t want to.”

Some have suggested that I ask for money from readers. I don’t want to torture readers. Do you know what my job is? Sharing! I will distribute these books to the people.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.