“Having been a troubled student myself, I think I’m just very empathetic to students who are having difficult times,” says Bernie Rhie, Chair and Associate Professor of English at Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts. Rhie teaches classes on the conception of the self, Buddhism’s influence on American literature and culture, and Asian American literature, among other subjects, while exploring ways to incorporate meditation into his teaching. Outside of Williams, he leads the weekly Williamstown Meditation Group. Before college, Rhie spent over three years living at Sonoma Mountain Zen Center in Santa Rosa, California. “I went there partly because I was very lost,” he says. “I went through a lot of mental health stuff when I was a teenager. I never managed to graduate from high school.” His time at the Zen center clarified for him that he did want to return to school, where he pursued literary theory.

Rhie’s Zen training also provided a foundation that sustained him when one of his children had a life-threatening medical emergency and a 20-day hospital stay. After this traumatic time for his family, he reconnected with a holistic approach to teaching and brought together his academic pursuit of literature and his personal background in Zen—a union that has proved urgently appealing to his students. Opening up his current course, “Zen and the Art of American Literature,” to 90 students per semester still didn’t allow him to accommodate everybody interested this year. Tricycle caught up with Rhie to learn more about his approach to teaching and why it is so important for students right now.

Why did you start studying literature? It was in my literature classes that I could engage in conversations and talk about things that seemed most resonant with what I had been learning on the cushion at the Zen center: really textured explorations of consciousness and human suffering, and also human happiness and joy. That was in the mid-90s, and this was at the height of literary theory and a whole really powerful wave of philosophical thinking that was about the sense of self that we have. Is it real? Is it an illusion? Is it constructed by language? I thought, wow, that really sounds like Buddhism! So I really got into theory as well.

Eventually you became a professor of English literature. What led you back to Zen and why did you bring these two domains together? I did not try to integrate them at the beginning. When I did the English literature thing, I wanted to go all in and do it on its own terms. In the background my Buddhist practice and experience was informing what I found interesting, but I felt like they were too far apart on the surface.

But Western theory was still just theory. You could talk all day about the deconstruction of the self, or the critique of a subject, but it would be just at the level of ideas. [Scottish philosopher] David Hume had this very Buddhist-sounding idea of the self as just a bundle of phenomena, but having those ideas is very different from having the experience, or a practice that can lead one to the experience. So in 2015, I decided that I wanted to explore teaching the stuff that actually was driving all this inquiry in the first place, and not trying to simply hint at it.

What led to that is my older son, who is 19, had a life-threatening medical emergency and spent 20 days in the hospital. He nearly died. I slept with him every night in the hospital and I think it was my Zen practice that sustained me. It was meditation in the waiting room or by his bedside that gave me the ability to make space to hold all the really intense emotions I was going through, without being overwhelmed or destroyed by them.

That was a really traumatic event, which took months, and really years, for him and the whole family to heal from. During that time, I actually left my job [at Williams College] and taught for two years at a high school because we all needed a change of scenery for the purpose of healing and recovery. Teaching high school kids reconnected me with an element of teaching that I think I had lost sight of a litte: teaching the whole person. Not just teaching minds. I coached. I advised. . . That really changed the way I wanted to approach teaching. When I came back to Williams after those two years away, I said, “I’m just going to try teaching this stuff that I really care about, and teach the whole student, not just teach them cool ideas to train their minds.”

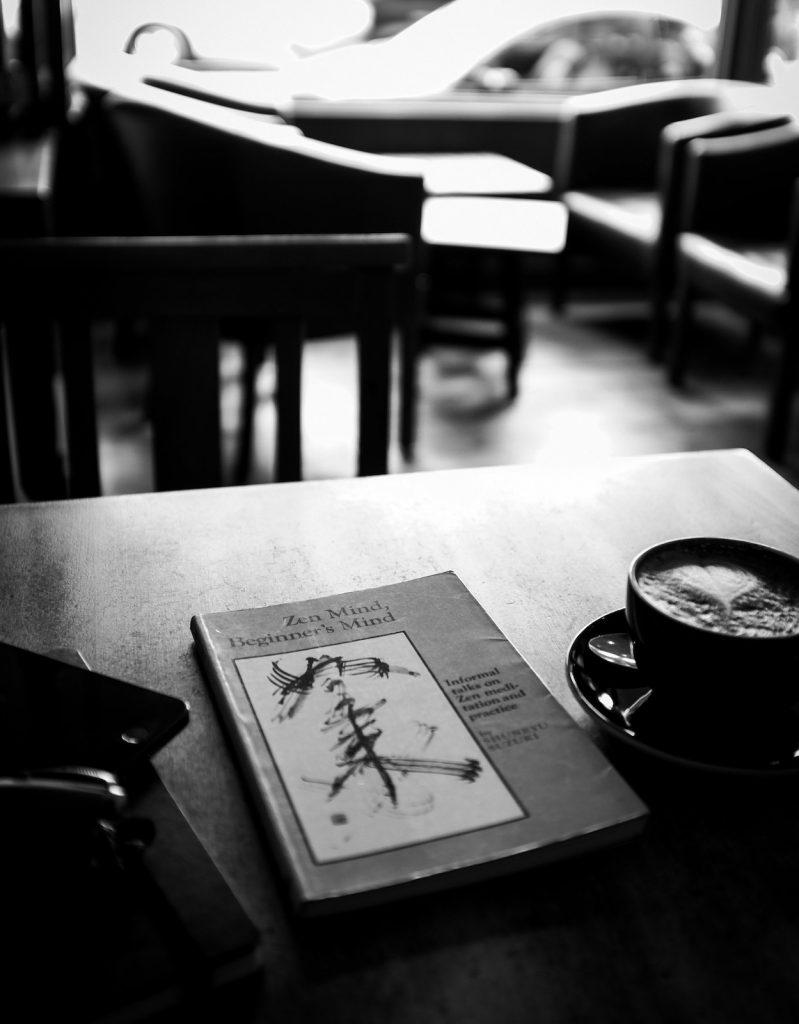

What are you teaching this semester? Because I’m chair of the English department at Williams, I’m not teaching as much as I ordinarily would. I’m only teaching one course this semester. It’s called “Zen and the Art of American Literature.” I couldn’t resist the title, but it’s not just about Zen or American literature, and more Buddhism in American culture. We read things like Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind; [Philip] Kapleau’s Three Pillars of Zen; Thich Nhat Hanh’s Peace Is Every Step; Natalie Goldberg and Norman Fischer on writing as practice; Gary Snyder and Jane Hirshfield… Eventually we end up looking at the places where Buddhism has had an influence more recently, like Black dharma. I’m teaching the anthology, Black and Buddhist, which just came out last year. We’re listening to a podcast Resmaa Menakem recorded with Dan Harris on racial trauma. David Loy’s Ecodharma and the climate crisis is also a really important unit. So it’s ways that practice can speak to American culture, but also to the concerns that students really feel are urgent and live right now. Meditation is a small part of the class—like the first 10 minutes—but it can be a very positive or negative experience for a person who has a lot of stuff going on.

During COVID, I taught a very small seminar of 28 students and we met in groups of seven because I thought connection was the most important thing. But the demand for the class has gone up and up and I had to turn so many students away. I’m teaching 90 students this semester, and I’ll teach another 90 in the spring, and still probably have to turn a number of students away. There’s a lot of hunger for this kind of teaching right now.

Can you talk about your Instagram account @Zen_Prof? When and why did you start it? I taught the 28-person version of the class in the fall [of 2020] and I realized I wanted a way to continue to offer some of what I had been offering in the class not only to the students who would now no longer be there, but also to other students at the college who might want some of that. It was explicitly something within the context of the pandemic. People were struggling, and I thought some of these practices might be of use. I think it struck a chord. I have an addictive personality and have actually deleted three different Instagram accounts over the past 10 years or so. But you have to meet people where they are.

Can you describe what you share on @Zen_Prof? Oh, it’s totally random. I think I just have this faith that what feels important and necessary for me now is probably going to feel that way for someone else. And I just try to just be genuine. At the beginning there were some very basic lessons. There’s actually a lot of really superficial meditation instruction out there. It’s amazing how many students come in thinking that meditation is all about making yourself stop thinking. So I made clear in some early posts that meditation is about finding your relationship to your thoughts, and not necessarily about making them go away. But in terms of recent practices, it’s sharing what feels like it would be a cool thing to do myself.

Why is it important to you to teach college students mindfulness right now? One thing a lot of people have been talking about is what some people call a mental health epidemic among young people, especially college students. I definitely see it on the ground.

Having been a troubled student myself, I think I’m just very empathetic to students who are having difficult times. So I think that’s one motivation for “why now?”

I also think that college admissions, the pressures of getting into college, what it’s like to be in college, the job market, and our desire to control everything—these pressures are a contributing factor. Then there’s the racial reckoning the country is going through and the catastrophe of the climate crisis—existential concerns that students are quite right to have about their futures. All of this is factoring into psychological struggles in classrooms on campuses.

But I also think that talking about this as a mental health epidemic is too limited. What we neatly categorize as a mental health issue is a much broader crisis—a spiritual crisis or an existential, species crisis. I think it’s something that requires more than just psychological services at a particular campus. Those services are really important, but I think psych services, chaplains offices, and professors all need to play a role in giving students new frameworks and ways of imagining a future—and a present—that seems livable to them. We’re trying to educate people who can lead the world in the future, or just live fulfilling lives in the future.

We need to educate young people so they can face with resilience and imagination the work necessary to engage in anti-racism, climate activism, and all that stuff. Academic discussions about race have been on college campuses for a while now, and I think one reason I really appreciate having the chance to teach some of this stuff is because we’re having necessarily intense discussions in classrooms about racism, anti-racism, white privilege, and more. They bring up a lot of feelings and that’s natural. But I think that’s where the merely academic approach to these topics doesn’t serve students or our communities well.

What are some of the unique challenges of teaching college students mindfulness and how do you approach them? Teaching about Buddhism always requires a soft touch. In whatever context, at whatever age, people often come to practice because they’re suffering. I think that teaching at a college campus, especially a selective campus like Williams, there’s a lot of pressure, so it’s important to be very gentle about the practice. It’s important to be aware that people are potentially going through very difficult things all the time, and that there may be trauma in the room. A very important resource for me is David Treleaven’s work on trauma-sensitive meditation instruction. I always offer modified forms of mindfulness that are meant to be sensitive to the fact that people may be recovering from trauma, including anchors other than the breath, like using sounds as an anchor. And I’m just really clear with them that it’s up to them how much they want to try.

See here for a practice on Rhie’s @Zen_Prof Instagram account for using sound as an anchor.

What does your daily practice look like? My original training was very much Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind Soto Zen practice. But one of my fellow students at Sonoma Mountain Zen Center was Ezra Bayda. He became such a close friend and mentor figure. So I’ve been a student of Ezra’s since the earliest days of my practice. Basically, the kind of practice I do is the kind he talks about in his books and the kind that [Zen teacher Charlotte] Joko Beck talks about in Everyday Zen. I’m not super strict or traditional. The essence of the practice is kind of like a Zen version of vipassana: just sitting, open awareness, but also with noting or labeling thoughts. I do a minimum of two 45-minute sittings a day and will maybe fit in a third or fourth in a day if I can. I’m not a good teacher, or a good husband or parent, if I don’t.

♦

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.