Dharma

The heart of Buddhism is the dharma, a term central to Buddhist traditions yet sometimes challenging to grasp. You will most often see the word dharma referring to Buddhist teachings, and while not all traditions agree on every detail, certain foundational teachings remain consistent throughout Buddhism. In this resource, we explore other uses of the word dharma and the core insights shared by Buddhists worldwide, beginning with the role of faith and moving through key ideas like karma, rebirth, impermanence, and enlightenment. These teachings are practical tools designed to help us live with mindfulness, compassion, and clarity.

Table of contents

- What Does Dharma Mean?

- Where Does Faith Factor into Buddhism?

- Samsara, Karma, and Rebirth

- The Four Noble Truths

- The Eightfold Path

- The Three Marks of Existence

- The Three Poisons

- Dependent Origination

- Nonself

- The Five Hindrances

- Buddhist Virtues

- Enlightenment in Buddhism

- Nirvana in Buddhism

- The Silence of the Buddha

What Does Dharma Mean?

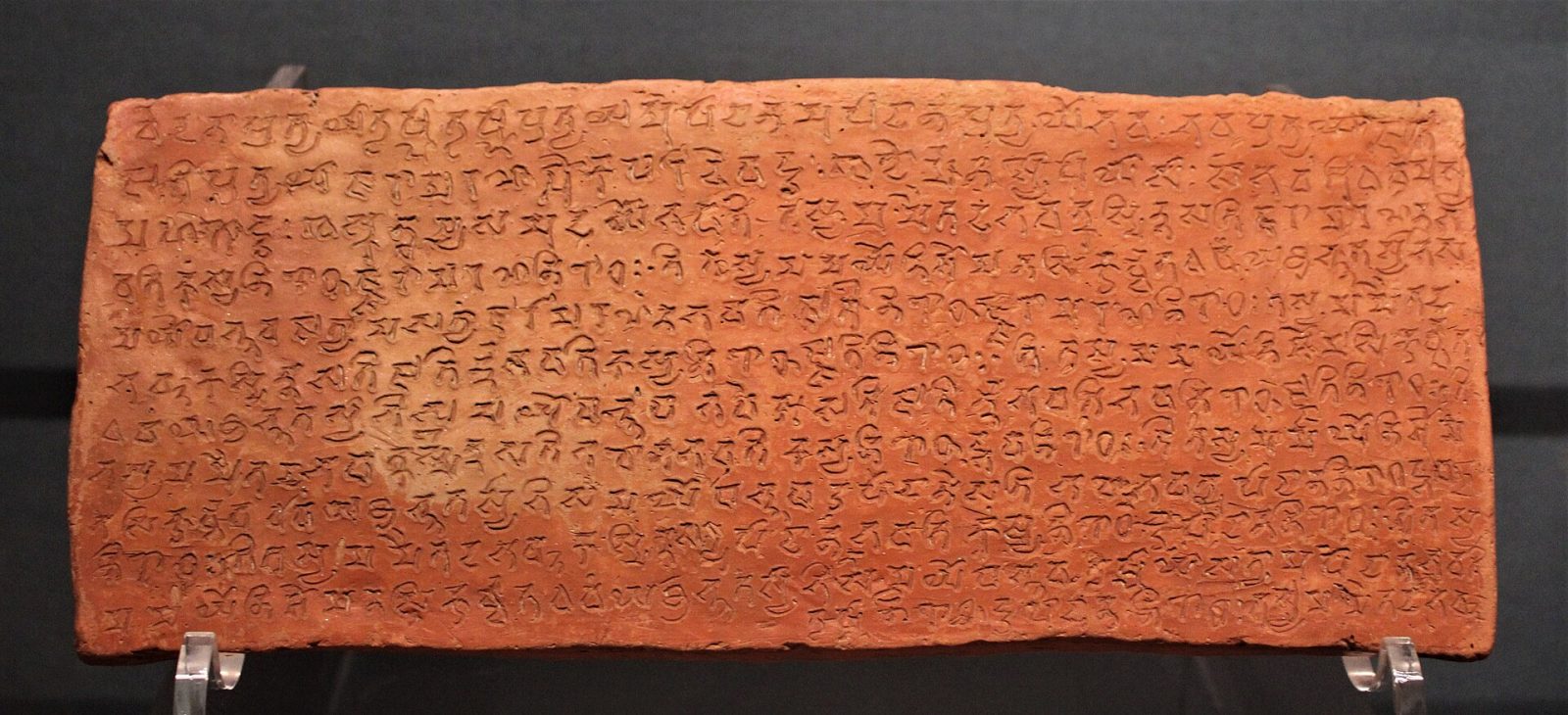

The term dharma (Skt.; Pali: dhamma) predates Buddhism and has deep roots in South Asian culture. Originally found in Vedic literature—ancient hymns that are sacred in Brahmanical traditions—dharma initially referred to the cosmic order and the duties required to maintain it. Early Vedic texts known as the Dharmashastra (“treatises on dharma”) describe how caste, gender, and life stages define a person’s social responsibilities. The Buddha was familiar with the earlier meanings of the term dharma, but he and his followers significantly redefined the concept. As Buddhism spread, the term dharma took on several meanings within the tradition.

First, as one of Buddhism’s three jewels—the Buddha, dharma, and sangha—dharma typically means the Buddha’s teachings or doctrines (often called buddhadharma). It can refer broadly to all the teachings, or more specifically, to an individual scripture or discourse. This is the most common use, and you will frequently see it in popular media capitalized as (D)harma when referencing Buddhist teachings, although convention has moved away from capitalization.

Second, dharma signifies the eternal, natural laws governing our reality. Key ideas such as impermanence and karma are seen as objective realizations about how things work. In this sense, the dharma is what the Buddha discovered to be true about the universe.

Third, in its plural form, dharmas describe the building blocks for all phenomena. These elemental dharmas are the underlying constituents of nature that arise and fall away moment to moment. This usage is common in many Buddhist philosophical texts.

Because of dharma’s multiple meanings and broad use, understanding the term in its different contexts can be challenging but is essential for studying Buddhism.

Where Does Faith Factor into Buddhism?

Faith (Skt.: sraddha; Pali: saddha) plays a central role in Buddhism, though contemporary teachings shaped by Buddhist modernism often downplay its significance. Historically, faith refers to a foundational trusting confidence in the Buddha and his teachings, and cultivating faith has always been a key part of Buddhist practice.

Early Buddhist texts present faith as a powerful motivator. Rather than unquestioning devotion to a teacher or doctrine, faith is a confidence born from personal experience and insight. While most Buddhist traditions do include teachings—such as rebirth, karma, or other buddha worlds—that may appear to require acceptance beyond immediate personal experience, these beliefs typically support or enhance faith rather than define it. Faith encourages practitioners to follow the practice and moral guidelines and to strive toward awakening, serving as a stabilizing force through periods of doubt or difficulty. Faith also includes trust in the workings of karma—the understanding that our actions bring results, positively shaping future experiences or perpetuating suffering. Thus, faith supports moral living, reinforcing the importance of right conduct on the Buddhist path.

People new to Buddhism may hesitate to embrace faith, associating it negatively with dogmatic belief or religious authority. Such hesitation can overlook Buddhism’s nuanced understanding of faith and its central role in the teaching. Buddhist confidence and trust aren’t just passive acceptance; they’re an active, reflective state of mind that is strengthened by observing the fruits of practice firsthand. To even begin on the path, a practitioner must have faith that the Buddha’s teachings are genuine. Still, such skepticism isn’t entirely unfounded: Buddhist teachings warn against misguided faith, which can inhibit awakening and contribute to suffering.

Recognizing the value of faith does not need to contradict a critical, reflective approach. Faith guides practitioners through challenges, sustains commitment, and provides encouragement along the path. Rather than diminishing personal agency, faith in Buddhism supports growth, practice, and awakening. Embracing faith, when understood clearly, deepens practice and reminds us that Buddhism balances reason and trust, skepticism and devotion.

Samsara, Karma, and Rebirth

Samsara, karma, and rebirth are foundational beliefs in the Buddhist worldview that originated in the early Vedic traditions of South Asia. These interconnected terms are often lumped together, though each carries its own depth of meaning.

Samsara refers to the ongoing cycle of birth, aging, sickness, and death experienced by all beings. Within this cycle, beings move through six realms by means of dying and being reborn—as gods, demigods, humans, animals, ghosts, or hell beings. Regardless of the realm, all beings—even gods—remain locked into samsara’s continual process of change. The human realm is most conducive to the Buddha’s path because we experience a balance of suffering and happiness. Instead of being caught in either extreme, we can cultivate insight into how the mind contributes to this cyclical process.

Iconographically, samsara appears as the wheel of existence (Skt.: bhavacakra). At its center are ignorance, desire, and hatred. Surrounding these core afflictions are the six realms and often the twelve-linked chain of dependent origination, which keeps beings stuck in samsara. Grasping the wheel is a fierce demon, identified variously as Mara (the demon of delusion), Yama (the king of death), or as a symbol of impermanence.

The Buddhist path aims at nirvana, complete liberation from the suffering of samsara. In other words, the goal is to get off the wheel. When the Buddha attained enlightenment under the Bodhi tree, he recalled numerous past lives wandering through samsara. Recognizing the nature of suffering, he taught the way out of samsara as an eightfold path.

Karma literally means “action.” It is the engine that propels beings through samsara. Karma is the law of cause and effect tied to the intentions behind physical, verbal, and mental actions. Every intentional action brings a future consequence, in this lifetime or another. While everyone has accumulated karma from previous and present lives, it remains mutable. Each moment allows one to think, speak, and act skillfully, moving away from the clinging and delusion that perpetuates suffering. In other words, we can work with our karma toward a better future.

Since the Buddha’s days, questions about rebirth have persisted. The Buddha sometimes declined to answer questions on rebirth, suggesting such inquiries were irrelevant to the removal of immediate suffering. Nevertheless, rebirth remains intertwined with his teachings on karma and samsara, and interpretations continue to be debated across Buddhist traditions.

The Four Noble Truths

The four noble truths form the core of Buddhist teachings. While commonly called the “four noble truths,” this translation can be misleading. The truths themselves aren’t noble; instead, they are truths understood by someone who is noble or awakened. In other words, these are “four ennobling truths” or the “four truths of the noble ones” on the path to buddhahood.

When the Buddha attained enlightenment under the Bodhi tree, he awakened to four fundamental truths about human suffering:

- The truth of suffering’s existence: Life involves suffering (Skt.: duhkha; Pali: dukkha). This doesn’t mean life is only misery. Happiness exists, but even happiness is ultimately unsatisfying because everything changes. Impermanence (anitya; anicca) ensures nothing lasts; we all experience birth, aging, sickness, and death.

- The truth of suffering’s cause: Craving (Skt.: trsna; Pali: tanha) fuels suffering. And, our attachments and aversions—to things, people, ideas, and experiences—drive craving. Fundamentally, we suffer when we want things to be different: more, less, bigger, smaller, or just wanting things to stay the same. Ignorance of craving is the root of suffering.

- The truth of suffering’s end: Suffering can end. If craving ceases, then suffering cannot exist. Removing desire, hatred, and ignorance—the three poisons—leads to freedom from suffering. Achieving this freedom is called nirvana (Skt.; Pali: nibbana), liberation from the karmic cycle of rebirth. It’s a big task, but it is possible.

- The truth of the eightfold path: The Buddha provided a path—the eightfold path—showing us how to reach liberation. This path guides moral actions, mental training, and cultivating wisdom. Known as the middle way, it avoids extremes of self-indulgence and self-denial.

Initially, the Buddha hesitated to teach these truths, believing them too difficult for most people to understand. According to the sutras, the god Brahma Sahampati intervened, convincing the Buddha to share these insights. The Buddha then delivered his first sermon to his former companions, five ascetics, who immediately understood his teaching and attained awakening.

Illuminated by the Buddha and accessible to all, the four noble truths reflect life’s impermanent nature and offer a road map to enlightenment.

Read more about the four noble truths.

The Eightfold Path

The eightfold path outlines practical guidelines for moral living, mental training, and wisdom. Together, these guidelines offer a way out of suffering—the ultimate goal of Buddhist practice. The Buddha is often described as a great physician or healer, and the eightfold path is his medicine that can lead us to well-being. This path is the middle way between excessive self-indulgence and self-denial.

The eight guidelines are:

- Right view

- Right intention

- Right speech

- Right action

- Right livelihood

- Right effort

- Right mindfulness

- Right concentration

Though listed sequentially, these practices aren’t so linear. Practitioners usually develop them simultaneously, often grouping them into three categories: moral conduct (sila), mental discipline or concentration (samadhi), and wisdom (prajna).

Training in moral conduct involves right speech, action, and livelihood. This foundation of Buddhist ethics encourages practitioners to examine if their actions and speech cause harm or suffering. For some Buddhist traditions, cultivating ethical behavior in a monastic setting comes first, preparing the way for more rigorous mental cultivation.

Mental discipline includes right effort, mindfulness, and concentration. Right effort involves preventing unwholesome mental states from arising in the mind and cultivating wholesome ones. Right mindfulness means developing awareness of our thoughts, sensations, and surroundings to help free us from craving. Right concentration leads to meditative absorption states known as dhyana (Skt.; Pali: jhana), providing clarity and insight.

Wisdom training encompasses right views and intentions, sharpening our understanding of reality and our motivation to follow the path. In practice, wisdom emerges from and reinforces morality and mental discipline, guiding practitioners toward liberation.

The eightfold path is visually depicted as a wheel with eight spokes, emphasizing the interconnectedness of each step. Each spoke strengthens the others: Morality supports mindfulness, mindfulness aids concentration, concentration fosters wisdom, and wisdom informs our moral actions.

Ultimately, following the eightfold path transforms our lives, guiding us from suffering toward liberation. It provides a compass to navigate the complexities of life, ensuring each step we take is aligned with the Buddha’s teachings. Far more than a set of guidelines, it represents a commitment to cultivating a balanced and purposeful life.

The Three Marks of Existence

Buddhism describes all phenomena—including thoughts, emotions, and experiences—as characterized by the three marks (Skt.: trilaksana; Pali: tilakkhana) of existence: impermanence (anitya; anicca), suffering or dissatisfaction, and nonself (anatman; anatta). Everything within samsara, the cycle of death and rebirth in which all beings exist, is impermanent, ultimately unsatisfying, and without a fixed, eternal essence. Understanding these three marks is crucial for anyone on the Buddhist path to awakening.

Impermanence, the first mark, might seem simple enough, but the implications are profound. Nothing stays the same—even for a millisecond—and all conditioned phenomena change, decay, and break down. All mental and physical phenomena connect through an ever-moving web of causes and conditions known as dependent origination. And suffering is linked to a mistaken belief in the permanence of things, leading us to cling to and desire them to remain unchanged.

Suffering, the second mark of existence, is also the first noble truth. Suffering here includes the entire spectrum of life’s dissatisfaction. Even pleasurable experiences are ultimately unsatisfying because they are impermanent. Clinging to such impermanent experiences inevitably causes suffering. Attachment to worldly things isn’t our only source of suffering—clinging to a false sense of a fixed self also creates suffering, leading directly to the third mark of existence.

Nonself, the third mark, is one of the Buddha’s most important yet misunderstood insights. Nonself means that no permanent, unchanging self or soul inhabits our bodies; we have no fixed, absolute identity. Instead, our “self” is a constantly changing construct of physical, mental, and sensory processes dependent on numerous factors. While we naturally cling to the sense of a fixed self, the teaching of nonself challenges us to recognize our selves—like everything else—as impermanent and interdependent.

Understanding these three marks of existence can free us from our illusions about the world and ourselves, making us less self-centered, less attached to impermanent things, and less prone to suffering.

The Three Poisons

The Buddha taught that the “three poisons”—desire or greed (Skt., Pali: raga), hatred or aversion (dvesa, dosa), and delusion (moha)—cause most of our problems and the turmoil we observe in the world. These three harmful mental states can be countered by cultivating their respective antidotes: generosity (dana), loving-kindness (maitri, metta), and wisdom (prajna, panna). Buddhist practice emphasizes recognizing the poisons when they arise and learning to let them go.

We don’t have to look far to see the three poisons at work—they appear in everyday life and within our own minds and actions. When we envy a friend’s good fortune, feel anger toward a reckless driver, or cling to false beliefs, we experience these poisons firsthand. Such reactions, while natural, can lead to harm and suffering. Like ingesting poison that later causes illness, indulging in these mental states can bring regrettable consequences.

As a teaching metaphor, the Buddha describes the three poisons as fires in his “Fire Sermon” (Adittapariyaya Sutta): “Monks, all is burning . . . with the fire of desire, with the fire of hate, with the fire of delusion.” This sermon compared the poisons to consuming flames that disrupt our peace of mind. Buddhist practice aims to extinguish these flames and move toward nirvana and the cessation of these very fires. Sariputra, a leading disciple, described nirvana as “the destruction of desire, the destruction of hate, and the destruction of delusion.”

The visual symbol of the wheel of existence (Skt.: bhavacakra; Pali: bhavacakka) often portrays the three poisons at its center as a rooster, snake, and pig, each consuming the other’s tail. This symbolizes how desire, hatred, and ignorance continually fuel one another, perpetuating suffering.

Overcoming the three poisons is a practical endeavor. Buddhist traditions offer teachings and practices to manage these ever-arising emotions, encouraging us to recognize their harmful patterns and actively cultivate more helpful qualities, transforming seeds of suffering into the fruits of wisdom and compassion

Dependent Origination

Dependent origination (Skt.: pratityasamutpada; Pali: paticcasamuppada) is a core Buddhist teaching and arguably the most critical insight from the Buddha’s awakening. Translated as “dependent arising,” “conditioned origination,” “interdependent origination,” or “interbeing” (a modern rebranding by Thich Nhat Hanh that carries a slightly different meaning), this idea explains that nothing exists in isolation. Every phenomenon arises, exists, and ceases due to interrelated conditions. Each event, thought, and thing is part of a continuously shifting, infinite web of cause and effect. This insight challenges the notion of a permanent, independent self or soul, describing reality as a dynamic interplay of myriad conditions.

Commonly represented by the twelvefold chain of causation, dependent origination outlines how existence unfolds from ignorance to aging and death through interconnected conditions. Each link—from ignorance, volitional actions, consciousness, name-and-form, the six senses, sensory contact, feeling, attachment, clinging, becoming, birth, and death—arises in dependence on the previous link and conditions the next. Ignorance of this reality leads to unskillful actions, conditioning consciousness, and so on, perpetuating samsara, the endless cycle of suffering. Breaking this chain, particularly at the points of ignorance and volitional actions, is key to liberation.

Volitional actions (samskara, sankhara)—intentional acts—are especially significant. Conditioned by previous intentional actions, they plant karmic seeds, shaping future experience. Thus, dependent origination highlights Buddhism’s ethical core: Intentional actions have consequences, so cultivating wholesome intentions is vital. In short, plant good karmic seeds. Understanding this helps practitioners develop moral clarity, break the chain of producing harmful karma, and move intentionally toward liberation from suffering.

Each link in the chain is an opportunity to expand awareness. Generations of teachers have explained dependent origination to help cultivate detachment from a self-centered view and foster compassion and generosity. Ethically, it emphasizes mindful behavior, as each action and intention shapes future actions and intentions, echoing the principle of karma.

Dependent origination may seem abstract and complex, but its basic principles serve as a practical guide for mindful living. Recognizing how our actions impact ourselves and others, we can see our role in perpetuating or ending suffering. Interconnectedness encourages compassionate responses, alleviating suffering for ourselves and all beings.

Nonself

“Who am I?” is one of the many questions religions and philosophies attempt to answer, and Buddhism is no exception. Our names, relationships, and occupations inform our sense of identity, but many religions point beyond these everyday associations toward an eternal soul or self. Buddhism, however, offers a unique perspective: Ultimately, there is no permanent self at our core. This teaching of nonself (Skt.: anatman; Pali: anatta) is fundamental to all Buddhist traditions.

In the Buddha’s time, dominant Brahmanical traditions recognized the atman, an indestructible and permanent inner witnessing consciousness, seen as divine and untouched by birth or death. Merging with this eternal self with the godhead Brahman was the highest goal of religious practice. However, the Buddha introduced a radically different view.

Gaining insight into dependent origination, the Buddha recognized that all phenomena—including what we consider our “self”—exist only within a shifting network of causes and effects. Each person is a temporary assembly of body, sensations, thoughts, and consciousness, continually changing and dependent on numerous conditions. From this, the Buddha recognized that there was no eternal self beyond the network of cause and effect. The Buddha was careful, however, to avoid claiming that nothing exists or that death destroys individuality. Some scriptures thus emphasize that the nature of the self cannot adequately be defined by existence or nonexistence. Later Buddhist philosophers developed sophisticated explanations of memory, subjectivity, and karmic continuity across lifetimes without requiring a permanent self.

Modern thinkers have noted similarities between Buddhist understandings and contemporary views of identity formation. In a Buddhist context, the philosophical view of nonself is not just theoretical and speculative; its goal is practical—alleviating suffering. Recognizing nonself means understanding that difficult thoughts or situations aren’t permanent aspects of our identity. We don’t need to own every passing thought or emotion. Acknowledging this can liberate us from suffering.

Misunderstanding teachings about nonself can lead to nihilism, feelings of meaninglessness, or depersonalization. However, Buddhist teachings do not intend to deny identity but point out that our sense of self arises through innumerable shifting, interdependent factors. Indeed, the question “Who am I?” can be fully answered only within the broad constellation of relationships shaping our lives.

The Five Hindrances

The five hindrances are common obstacles encountered in meditation and Buddhist practice. Even if you haven’t heard of them, you likely experience them regularly. Frequently discussed in Buddhist teachings, these hindrances include sensual desire, ill will, sloth-torpor, restlessness-worry, and doubt. Despite their pernicious presence in our lives, Buddhism offers strategies to overcome these obstacles, enabling the practice to strengthen and mature.

Sensual desire refers to cravings for food, sex, possessions, and experiences. Such cravings cloud the mind, obstructing clarity. Considered a gateway for other hindrances, sensual desire has been compared to a bead of honey on the blade of a knife. To address sensual desire, monastics and other serious practitioners contemplate bodily impermanence or practice mindfulness, observing cravings without judgment and letting them pass naturally.

Ill will—malice, anger, or hostility—is the desire to see others suffer. Even justified anger hinders mental clarity and meditative progress. The Buddha compared a mind filled with ill will to boiling water. Cultivating loving-kindness (metta) toward those who trigger hostility transforms anger into compassion, cooling the boiling waters of the mind.

Sloth-torpor characterizes dullness, sleepiness, or lethargy in meditation, like stagnant water covered with algae. Contemplating life’s brevity and inevitable death generates a sense of urgency, motivating diligent practice and overcoming lethargy. But, before applying such antidotes, check to make sure you don’t just need some sleep!

Restlessness-worry includes anxiety, distraction, fear, and mental agitation. The Buddha compares a restless mind to wind-whipped waters full of ripples and waves. Such a mind resists the calm and openness needed for progress on the path. Practicing equanimity and calming breath exercises can help ease restlessness, making the mind more receptive and stable.

Doubt involves uncertainty about practice, one’s capabilities, or the teachings. A mind filled with doubt resembles a cloudy, murky pool of water—impossible to see through. Practitioners overcome doubt by closely observing thoughts and actions, clearly discerning what leads to suffering and what brings benefits.

Traditionally, the five hindrances are viewed as impediments. Yet they can also serve as valuable teachers on the Buddhist path, helping us understand our habitual ways of thinking. Rather than becoming discouraged, practitioners can recognize these obstacles as everyday experiences that can inspire dedicated practice, helping uncover inner strength and wisdom essential to moving closer to liberation and the peace of an unobstructed mind.

Buddhist Virtues

The paramitas (Skt.), or paramis (Pali), are the highest “perfections” or “virtues” that Buddhists strive to cultivate. Mahayana traditions (such as Zen and Tibetan Buddhism) emphasize these perfections, regarding them as essential qualities for bodhisattvas—beings committed to enlightenment for the benefit of all—while Theravada traditions also recognize and cultivate these virtues, albeit with a somewhat different framing and organization. Mahayana teachings typically list six virtues (sometimes ten), and Theravada traditions consistently list ten. The following virtues are central in Mahayana Buddhism:

Generosity (dana) involves giving material goods, serving others, and sharing the teachings of the dharma. Generosity counters greed and self-centeredness and, together with morality, forms the foundation of Buddhist practice.

Morality (sila) refers to ethical behavior in speech and action, often linked to Buddhist precepts. It provides stability and peace, supporting meditative practices.

Patience (Skt.: ksanti; Pali: khanti) is accepting difficulties and criticism without losing composure or responding in harmful ways. Patience serves as an antidote to anger and aversion.

Effort (virya, viriya) means enthusiastic exertion in following the path, overcoming obstacles, and cultivating virtues. Effort sustains practitioners amid internal and external challenges and is emphasized throughout Buddhist teachings. Scriptures and commentaries frequently mention the tremendous effort required to progress toward awakening.

Meditative absorption (dhyana, jhana) or concentration refers to developing mental focus through meditation. Concentration calms the mind, leading to insights, direct realization of the truth, and liberation from suffering.

Wisdom (prajna, panna) involves accurate, penetrating insights into reality—particularly impermanence, suffering, and nonself—helping practitioners transcend attachments and delusions. Wisdom often represents the culmination of these virtues, guiding practitioners to liberation.

In the Mahayana context, these six virtues guide bodhisattvas on their path toward buddhahood. Certain traditions also emphasize the importance of skillful means (upaya), resolve (pranidhana), power (bala), and knowledge (jnana) as essential qualities that support effective compassionate action.

Theravada Buddhism is less focused on the bodhisattva ideal, but it also encourages cultivating virtues across countless lifetimes, adding renunciation (Pali: nekkhamma), truth (sacca), determination (adhittana), loving-kindness (metta), and equanimity (upekkha). Metta practices have become particularly popular in the West, moving beyond Buddhist circles into secular mindfulness-based practices and therapies.

Beyond doctrinal understanding and differences, these virtues provide practical guidelines shaping every aspect of Buddhist life. Like the eightfold path, they offer a framework for ethical conduct, mental cultivation, and wisdom. By embodying these qualities, practitioners cultivate compassion and wisdom, benefiting themselves and others.

Enlightenment in Buddhism

Among Buddhist buzzwords, enlightenment and nirvana might be the most misunderstood and misused. Widespread usage sometimes suggests a dramatic event with all the universe’s mysteries downloaded into our brains like a cosmic software update. In Buddhism, however, enlightenment has specific meanings and is not easily attained.

The English terms enlightenment and awakening are both used to translate the Sanskrit and Pali term bodhi, meaning to awaken and to know. Translators preferring awakening seek to avoid the Western philosophical, mystical, and historical associations of enlightenment. Proponents of enlightenment argue that it better emphasizes the significance of the Buddha’s accomplishments. Regardless of which term is used, clarifying the Buddhist understanding is essential.

Enlightenment is direct insight into the four noble truths—suffering, its cause, cessation, and the path leading to cessation. This insight isn’t merely intellectual; it’s transformative, removing the roots of suffering—desire, hatred, and ignorance—and providing freedom from samsara’s endless cycle of birth, suffering, and death.

Understanding enlightenment involves distinguishing it from related concepts, like nirvana. Enlightenment refers to the direct insight into the truth of reality, while nirvana is the resulting state of liberation from samsara—the extinguishing of desire, hatred, and ignorance. In other words, enlightenment is the realization itself, and nirvana is the freedom this realization makes possible.

Traditionally, awakened beings fall into three categories: buddhas, solitary buddhas (Skt.: pratyekabuddha; Pali: paccekabuddha), and arhats. Buddhas realize awakening independently and then teach others. Solitary buddhas also attain independent awakening but do not teach. Arhats achieve awakening by hearing a buddha’s teachings and following the path, thus demonstrating to people that awakening can be reached.

Mahayana Buddhism introduces the ideal of the bodhisattva, an individual dedicated to the awakening of all beings. In Mahayana traditions, every being inherently possesses the potential for awakening. Bodhisattvas help others realize this potential.

According to Buddhist texts, the enlightenment of a Buddha involves remembering previous lives, foreseeing others’ rebirth based on karma, and fully understanding the mental afflictions that bind beings to samsara—all supernatural abilities attained only by enlightened buddhas. Texts emphasize that awakening is not achieved quickly. Instead, it requires sustained dedication to ethical conduct, meditation, and wisdom across many lifetimes. While traditions like Chan or Zen suggest awakening is immediately accessible, maintaining and embodying this realization in daily life requires the same diligent practice exemplified by a buddha.

Thus, enlightenment indicates directly seeing reality—free from desire, hatred, and ignorance—and sets the stage for attaining nirvana, the ultimate freedom from the cycle of suffering.

Nirvana in Buddhism

Nirvana (Skt.; Pali: nibbana)—a term that has entered English dictionaries and lent its name to a famous 1990s grunge band—is one of Buddhism’s best-known yet most challenging concepts. Nirvana represents Buddhism’s ultimate goal: complete liberation from samsara, the relentless cycle of birth, suffering, and death that characterizes life.

The concept of nirvana has its roots in South Asia, appearing in various philosophies and religions, including Jainism, Sikhism, and Hinduism. In Buddhism, nirvana means the extinguishing of desire, hate, and ignorance—the very sources of our suffering. The metaphor of fire being “blown out” captures the literal meaning of nirvana: the cessation of suffering’s flames and the subsequent peace.

Early Buddhist texts provide a concise definition. Nirvana is not about disappearing or ceasing to exist. Instead, it’s the end of processes that keep us chained to samsaric existence. Nirvana is described primarily through negation: the end of birth and death, unconditioned, unknowable detachment, an absence of craving, etc. Early scriptures deliberately avoid extensive speculation or philosophizing about nirvana, considering such theorizing irrelevant to actual practice and awakening.

As Buddhism developed, debates and varied interpretations emerged. For example, people wondered how the Buddha could remain in the world after achieving nirvana. Such questions led to distinguishing two types of nirvana: “nirvana with remainder,” achieved during life (with some karma remaining); and “nirvana without remainder,” complete liberation at death (Skt.: parinirvana).

The Mahayana tradition introduced another perspective, seeing nirvana and samsara as two aspects of the same reality. From this nondual perspective, Mahayana traditions emphasize our innate potential for enlightenment—our buddha-nature—already unified with nirvana. By making practice a less solitary endeavor, this philosophical development encouraged further discussion about compassion and the bodhisattva path to enlightenment.

Today, nirvana continues to symbolize Buddhism’s promise of peace and liberation from the cycle of conditioned life and suffering. Mindfulness and compassion enable practitioners to recognize and extinguish the desires and delusions that fuel their suffering. Nirvana is an attainable goal that underscores Buddhism’s pragmatic teachings: the end of craving and the peace that follows.

The Silence of the Buddha

Have you ever asked yourself: What am I? Is there a soul? Is the universe infinite? If so, you’re not alone. These questions animated religious and philosophical discussions long before the Buddha awakened. However, the Buddha’s response to specific perplexing questions was surprising: Don’t bother!

Throughout his teachings, people repeatedly questioned the Buddha about topics like the origin of the cosmos, the nature of the soul, and the afterlife. Buddhist scriptures contain numerous instances when the Buddha deliberately declined to answer these metaphysical inquiries, redirecting questioners to the practical path of awakening. His silence wasn’t due to a lack of interest, aversion to philosophical debate, or ignorance of the answer. Instead, it stemmed from his understanding that some questions simply do not contribute to the cessation of suffering.

In the parable of the poisoned arrow, the Buddha illustrates this point vividly. He describes a man shot by a poisoned arrow who insisted on knowing irrelevant details—such as who shot it, from where, and the type of arrow—rather than immediately removing it. The message was clear: Speculative questions distract us from addressing immediate suffering.

Buddhist tradition classifies these unanswerable questions as indeterminate or inconceivable. The Acintita Sutta has four imponderables, while the Culamalunkya Sutta enumerates fourteen difficult metaphysical questions. Similarly, in the Aggivacchagotta Sutta, the Buddha refuses to theorize about the eternal existence of the world. And the Sabbasava Sutta lists sixteen unwise reflections that lead to further ignorance and frustration. In each instance, the speculation is portrayed as a jungle or wilderness of views that generate misery rather than clarity, detracting from the practical pursuit of liberation.

The Buddha’s selective silence teaches an essential lesson: Our attention is best spent understanding suffering and how to end it, highlighting practical wisdom over theoretical curiosity. This approach doesn’t dismiss the value of inquisitiveness or the pursuit of knowledge but prioritizes questions that directly contribute to liberation. In our current world, filled with endless distractions, the Buddha reminds us that some questions can remain unanswered, allowing us to focus instead on practical teachings that guide us toward peace and awakening.

Buddhism for Beginners is a free resource from the Tricycle Foundation, created for those new to Buddhism. Made possible by the generous support of the Tricycle community, this offering presents the vast world of Buddhist thought, practice, and history in an accessible manner—fulfilling our mission to make the Buddha’s teaching widely available. We value your feedback! Share your thoughts with us at feedback@tricycle.org.