Big time sports is not normally viewed as a path to enlightenment. Most coaches are spiritual disciples of Vince Lombardi, the legendary coach of the Green Bay Packers, who is reputed to have coined the phrase “Winning isn’t everything, it’s the only thing.” Not so Phil Jackson. A Buddhist practitioner for twenty years, he has revolutionized coaching by leading the Chicago Bulls to three consecutive National Basketball Association championships with a Zen approach to the sport that centers on awareness training, selfless teamwork, and “aggressiveness without anger.” Through meditation practice and other techniques, he teaches players to experience the joy of being in the moment and to blend their individual talents with the consciousness of the group. As he puts it, “Being aware is more important than being smart.”

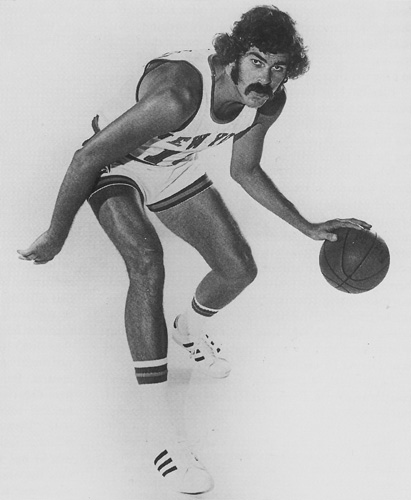

Born in Deer Lodge, Montana, Jackson, 48, is the son of strict, fundamentalist Pentecostal ministers. While studying philosophy, psychology, and religion at the University of North Dakota, he flirted with the idea of going into the ministry himself. But his athletic gifts took over: he was drafted by the New York Knicks in 1967 and starred as a forward for them until 1978. His interest in spiritual matters resurfaced in his early thirties when his playing career was winding down. During the 1974 off-season, some friends in Montana who had studied at the Mount Shasta Abbey introduced him to Zen practice. “It helped me get through a difficult time in my life,” he says. “For me, the loss of playing basketball was tremendous. It was a death—a process very few people go through, except professional athletes. It was good to go through it with the support of a belief system and a form of meditation, to come to grips with myself as a person.”

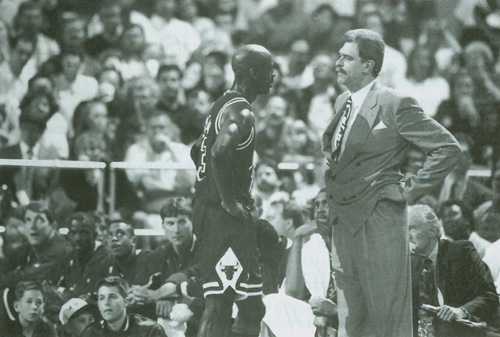

Jackson, who carries Shunryu Suzuki’s Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind with him everywhere, continued to practice Zen meditation and yoga after he retired in 1980 (after two years with the New Jersey Nets) and discovered that the knowledge he had learned on the cushion could be useful in his next career: coaching. I caught up with him on the road earlier in the season. A few months earlier, the Bulls’ star Michael Jordan, had retired from the game, and Jackson was trying to formulate a vision for his new team. This interview was conducted for Tricycle by Hugh Delehanty, a senior editor at People Magazine.

Tricycle: How would you describe your spiritual practice?

Jackson: I use the term “Zen Christian” to describe my personal beliefs, because I still like to think of the Christian precepts I learned as a child as the basis of how I live. Do unto others as you would have them do unto you—what I call the dispensation of grace, the idea that love is an all conquering force. The Zen part is living in the moment—that brings the now into Christianity, which most of the time is focused on heaven and hell. A combination of the two makes sense to me, because I think practice is what Christ was doing when he stepped away from his disciples and became one with the Father.

Sitting with a relaxed mind and soft focus on life is the thing that helped take some of the edge off my hard fundamentalist background. It [Pentecostal teaching] was judgmental, right and wrong, positive and negative—looking at life in dualities. Being a coach in the NBA, where everything is measured in wins and losses, pluses and minuses, it’s been a gift for me to have a sitting background.

Tricycle: Do you feel that basketball is a samadhi experience?

Jackson: I always have. It’s a warrior attitude—without having to be violent. When I came into the NBA as a coach five years ago, basketball was all about power—who had the biggest guys, who played the roughest game, who could intimidate who. Our system moves away from that. The whole concept is to defy pressures, to work against the other team’s force. Basically we try to get the other team to overload in one area and then work with their energy [to defeat them].

Tricycle: That sounds like t’ai chi basketball.

Jackson: Exactly.

Tricycle: How do you teach that to your players?

Jackson: It has taken a lot of videos, and a lot of humor. The most famous example was a few years back when we were playing the Detroit Pistons [then the NBA champions]. I interspliced clips from The Wizard of Oz into the fame film to show all the mistakes we made against Detroit’s strengths. It was a softer way of conveying correct behavior without a lot of criticism.

We also use the idea of the circle. The circle is a spiritual symbol for the Native Americans because it encompasses all of life—the unity that is all one. We stand in a circle when we meet on court; we bring everybody into the group. The basketball is a circle; the hoop is a circle. These are symbols or reminders that the circle is one. We talk about things that to open up the players’ minds and bring them ideas from other cultures to help them develop as a team.

Tricycle: How do the players respond?

Jackson: Sometimes it’s hard to know how to reach twenty-five-year-old kids with lots of money who are pretty set in their ways. Obviously the most important person we had to win over was Michael Jordan. The only reason that we’ve had such great success as a team is that he realized he couldn’t do it alone, even though he tried for a couple of years. His efforts fell short because we didn’t incorporate the group as a whole. After we won Jordan over, we talked to the players about gestalt and the idea that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts—to make them understand that a great player can’t do it alone, and that five individuals can’t beat a team that’s dedicated to working together.

Tricycle: How did your Buddhist practice help you in this?

Jackson: When I talk about soft focus, I mean not insisting that my way be the only way, not letting the I get in the way of the we. I give a lot of authority to my coaching staff. That helps. I let the club know that the [assistant] coaches’ opinions are as important as mine. I also let the players know that their opinions matter, that a lot of times they understand what’s going on in the moment better than we do on the bench. I won’t call plays. I’ll let them figure out how to organize themselves on the floor. That gives them a sense of self.

Tricycle: Was Jordan a difficult player to coach?

Jackson: No. When I took over the Bulls, I told him, “What I want you to do is going to be harder on you than anyone else on the team. You’re not going to average thirty-five points a game. It will mean giving up the ball and playing without it.” And he understood. I said, “I hope we have the kind of personnel to do it. On paper we don’t. But as we play, we will, because everyone will grow.” And he had faith. I think that’s the hardest thing for an NBA player—to look at someone whose capabilities don’t match yours and trust him to do the right thing in critical situations. To trust [guard] John Paxson to shoot, to trust [center] Bill Cartwright with the ball in the post. That’s what made this team a winner: the players began to trust each other. The ones with the greater talent were able to play with the ones with lesser talent and share the glory with them. It’s as simple as that.

Tricycle: Did you ever worry about giving up so much control that you lose the respect of your players?

Jackson: Yes. I was nervous about that during the first half-year I coached. Then I became more and more confident that I was doing the right thing. Michael had moments when he took the game over, and we let him know that that was okay. But toward the end of his career he got better and better at standing back and helping others bring their game up to another level. It has been said that he wasn’t as good a team player as Magic Johnson or Larry Bird because they helped their teammates out more. That’s completely false. By the end of his career, he was as great a team player as Magic or Bird because he didn’t have to have the ball in his hands as much as they did. When you are as great a scorer as Michael and you don’t have the ball, everybody is paying attention to you and not the ball. So your teammates can stand up and play bigger roles.

Tricycle: What else do you do to prepare your players?

Jackson: I was talking recently to a friend about some behaviorist therapy he went through to deal with the problem of indecisiveness. His therapist had him strip down to his shorts and balance on one leg while he organized his thoughts. He learned that the body and mind can’t get it together to balance in a yoga position and use linear thought at the same time. His experience reminded me of how much we try to clear the minds of our players so that they are not playing with an agenda. The player isn’t thinking how he can score; he’s just letting things come without making a conscious decision about what’s the next thing he’s going to do to attract attention. What he can do to make the game come to him is to have a clear mind—not thinking, just doing. I hate that [Nike] commercial that has co-opted everything, but it’s so right on.

Tricycle: Is that the samadhi experience you were talking about earlier?

Jackson: Yes. That’s why some people get so hooked on playing basketball. When you’re a basketball player, you have all these samadhi moments on the court: your heart is pounding, your blood pressure is high, and yet you’re wonderfully calm and peaceful. It’s no wonder that we had a drug problem in the NBA. There’s nothing that can replace the highs you get in basketball, except maybe a drug experience.

Tricycle: How do you teach awareness to your players?

Jackson: We try to use it as a principle in a lot of things we do. We even bring a guy who teaches meditation to training camp so that the players will learn what that experience is like in a seated position and can find it again when they become active. Basically, we try to give them the idea of being able to focus, by watching their breath and dealing with the thoughts that come into their minds. Not everyone can get there, we accept that. But if we can reach two or three of the guys on the club and get them on the court at the same time, then they can influence the other players. I believe that if we can create a little space in the consciousness of these players, not only will they be better players, they’ll be better people.

Tricycle: Which players specifically have taken to this approach?

Jackson: B.J. Armstrong and Horace Grant have a lot of curiosity in this area. However, the most serene person I’ve ever seen is Michael. He has a great sense of awareness. He loves the feeling of being calm in the midst of a storm of activity. He’d like to have that feeling every waking hour. People say Michael has a gambling problem. He doesn’t have a gambling problem; he’s got a problem of loving to have that storm going on around him and feeling like he’s in the eye of it.

Tricycle: What obstacles have you encountered with your players?

Jackson: Ego. Selfishness. What happens is that in the seventh, eighth, and ninth grades, 80 percent of these kids are noticed and given privileged lives. From then on, everything is paid for. By the time we get them, at age twenty, they’ve had maybe eight years of a programmed existence where everything has been spoonfed to them. They’ve got shoe people coming after them, sportswear people, agents, lawyers—they might have an entourage of five to ten people vying for their favor. So for them to enter into a twelve-man unit and submit their will to the good of the whole, it’s difficult. Then they have their successes and failures reported in the media—all these things work against us. We’ve been fortunate to get very productive, manageable kids, because there are so many elements working to make this a selfish endeavor. Most of our players have a religious background, so they relate intuitively to things of the spirit.

Tricycle: Do you recruit for that?

Jackson: When I interview prospects, I talk to them about their religious background and their family. I also ask them if they’ve played in a band or sung in a choir. I want to know if they can make harmony. Most of our kids come from middle-class, two-parent families. Work ethic is important. We tend to choose kids with character, not just great athletic ability.

Tricycle: How is your style of coaching different from that of New York Knicks coach Pat Riley, who’s known for his winning-through-intimidation approach to the game?

Jackson: Pat is a person who works hard and uses his work ethic for great productivity. It’s a great form of discipline. But my feeling is that it’s restrictive. I encourage freedom. What I believe in is harnessing a certain amount of discipline so that the players can have freedom within parameters. I think that’s the difference. And the rest of the stuff that goes with it—our life off the court when we travel or communicate with each other—is expanded. I like to provide a real life for these guys so they enjoy what they’re doing—so that it’s not punishment.

Tricycle: Is it true that you almost became a minister when your playing career ended?

Jackson: Yes, I looked at going to a Unitarian seminary. I was looking for a New Age religion, and I thought the Unitarians might have that. In the end I wasn’t meant to be a minister, but my whole life has some of that in it. Chiding, gently nudging people. I told my wife that maybe twelve was the number of parishioners I was supposed to have—twelve players.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.