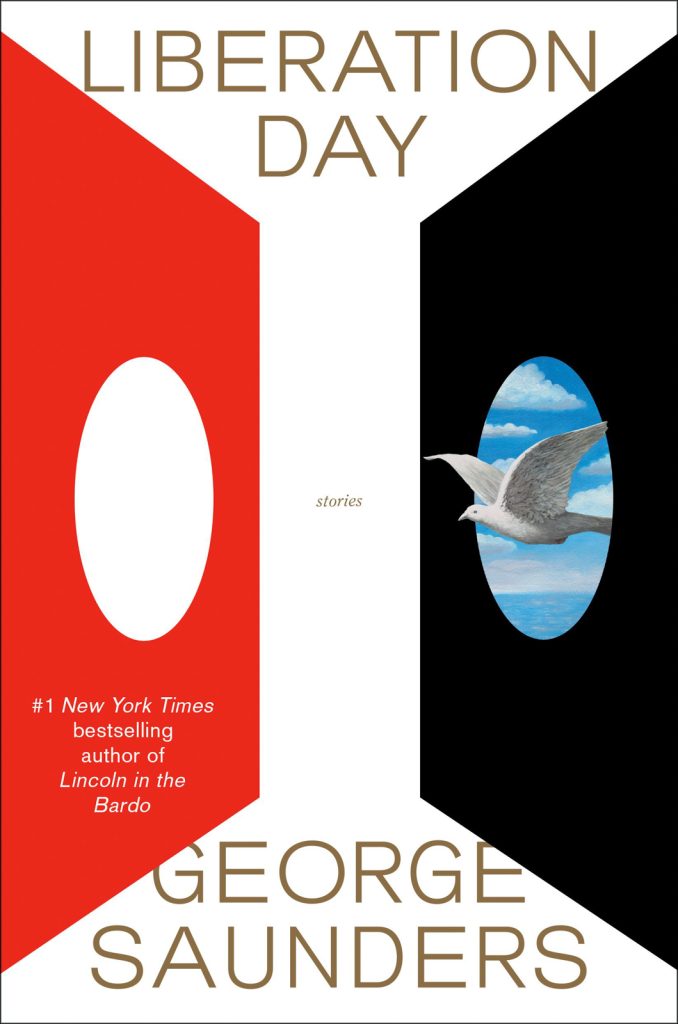

Liberation Day is a fine new short story collection by George Saunders, who has practiced for many years in the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism. Four of the nine stories in the collection are new, the other five having previously appeared in the New Yorker.

By George Saunders

Random House, October 2022, 256 pp., $28, hardcover

Despite his lightness of touch and phantasmagorical humor, Saunders is a precise and learned writer, with a style echoing Chekhov, Vonnegut, Hemingway, and Steinbeck, laced with the flavors of Terry Southern, Monty Python, and Bruce Springsteen. The new book’s title story is a walloping leadoff in the Saunders tradition of heart-stoppingly moving, funny speculative fiction. “Liberation Day” is about a mind-blanked artist, enslaved and shackled to a wall in a rich man’s mansion; it’s about the plight of all artists in the 21st century’s hellscape of grief and disaster; about the mindless, snowballing cruelty of people and their lust and art and beauty and helplessness.

Though there is a lot of humor in it, Liberation Day is less fanciful and playful than Saunders’s earlier work, more deeply anchored in the events of our own dark times; one of the stories, “Love Letter,” dispenses almost entirely with the author’s untamed imagination, speaking with unusual directness of the current political situation in the United States. Taken as a whole, these stories are grappling with the chimeras of self in the modern world, a subject treated with an undeceived openheartedness, intricately connected with the author’s long study of Buddhism.

Saunders is a phenomenal teacher. I was lucky enough to take a writing class from him once, “The Russian Short Story in Translation (for Writers).” Once, in discussing the literary genius of Anton Chekhov, he basically described what has become his own gift:

[…] the whole time you feel this moral presence: “Anton, what should I believe? What do you want me to believe?” “Love is good.” “No, it’s not good.”And he’s constantly guiding you by the shoulders. Every time it gets too simple he goes, “No no no no no…no no…no no no no…no no.” And at the end he just kind of drops you off a cliff.

Whether in the classroom, in conversation or in his work, Saunders constantly provides an example by way of his own generosity and awareness; over the years he has been holding less and less back and offering more and more. The autobiographical piece “My Writing Education: A Timeline,” published in the New Yorker in 2015, provides a brief, clear introduction to his approach as an artist and teacher. He also writes a Substack newsletter—a writing class, really—called Story Club, which I can recommend very highly to any writer or reader interested in the art of fiction.

When I caught up with Saunders to discuss the new book, he was busy packing up the house in the Catskills where he’d lived with his family for many years. His children are grown now, and he and his wife have moved to California. He was in a reflective, maybe nostalgic frame of mind.

I started by asking him about a letter he found while packing up his house, written to himself many years earlier as a sort of eulogy to an abandoned book of stories. He’d posted this letter to Story Club, and it struck me that some of what it expressed seemed very present in his work now.

“I have my sense of beauty,” he’d written. “My work must be the expression of that, in whatever form is needed. Fuck artifice and the imaginary voices of short-story purists, etc. Listen only to your memory. What comes will be beautiful.”

In the letter, you wrote, “I have nothing to offer to the world when I’m careful.” Yes. That was an amazing thing. I was just going through some old files and had totally forgotten ever writing that letter. And there it was: me talking to me, across the years. All the stories in that book were there, and I preserved them, but I knew they weren’t any good. And it was such a thrill to go, Oh, hey, that guy, that 29-year-old me, he’s a little tight-assed, but he makes sense, you know; he cares.

How much do you still agree with him? I think that guy had one more thing to learn. At that time I was still thinking I was going to write about my actual life, and about childhood and all that kind of stuff. But otherwise, yes, that letter still speaks to me.

I have a very controlling mind, which is how I get a lot of work done. I do a lot of revision, but there’s a magical, essential moment when I just veer off the track of control and let something bigger get in there. So he was onto something, you know. But what he hadn’t realized yet was, if you want to tell your deepest truths, you don’t necessarily have to stick with the biography. You don’t have to stick with realism, you don’t have to stick with your actual lived experience. You don’t have to have the story all mapped out in advance. You can approach it another way.

A person might have an idea of who she wants to be as a writer, or as an artist, but her actual tendencies—her actual strengths, the things she’s good at doing, the things she likes to do, the things she can make really leap off the page—might be telling her something different.

“If you want to tell your deepest truths, you don’t necessarily have to stick with the biography. You can approach it another way.”

Writing can have the positive effect of making us realize that we have so many different voices in us, and so many different personalities. Then you choose one, but you don’t really choose one, you just, let’s say “give vent to one,” temporarily.

One person gets on stage for a second. Right, and that’s great, because then, if the person you happen to be at that moment turns out to be not the best, you go, “That’s OK, she’s just passing through. She’ll be out of here soon.” That is, we can do things—through revision in writing and, I guess, through spiritual practice, in “real life”—to urge better, more interesting versions of ourselves to come forward.

What’s the better self? Well, I don’t know. I guess you know it when you feel it. But for me, there’s a feeling of quiet-mindedness and fondness for everybody and everything, and a little more sense that things are workable, like: OK, whatever happens, it’ll be all right. And certainly there’s a reduction in my anxiety level—because that’s my worst enemy, anxiety.

So I know it when I feel it, but it’s not reliable. I can’t just say, Oh, let’s be our best self today, you know? It depends on how I wake up feeling. Which is a pretty wobbly arrangement.

That’s how I’m understanding Buddhism these days; I’m not meditating a lot right now, but I’m thinking, “Well, I can still be working with my energy, trying to arrange my mind so that if I’m needed, I’ll be more useful.” But that’s a hard thing to do mechanically, just by willpower. Which is why we practice. But my main “practice” at the moment, seems to be “noticing how wobbly I am when not meditating.”

I remember first talking with somebody who knew a lot about meditation, and I made some joke about, “Absolutely not, I’ll never be able to do it,” and the response was, “Well, no! Nobody can!” Right. It’s like working out, or something: “Oh, I could never lift weights”—Yeah, you can lift weights. You might suck at it, but you can get in there and give it a shot.

You can lift, like, a pound. Yeah. You can lift air, come on!

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.