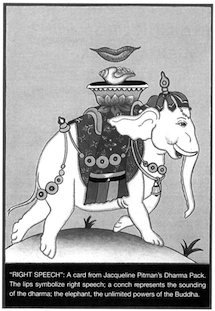

Right Speech, or sammavacha, is the third step of the Eightfold Path, which is the fourth and last Noble Truth preached by Shakyamuni Buddha. The following is a collection of classic and contemporary views of Right Speech.

“And what, friends, is right speech? Abstaining from false speech, abstaining from malicious speech, abstaining from harsh speech, and abstaining from idle chatter—this is called right speech.”

“And what, bhikkhus, is wrong speech? False speech, malicious speech, harsh speech, and gossip: this is wrong speech.

“And what, bhikkhus, is right speech? Right speech, I say, is twofold: there is right speech that is affected by taints, partaking of merit, ripening on the side of attachment; and there is right speech that is noble, taintless, and supramundane, a factor of the path.

“And what, bhikkhus, is right speech that is affected by taints, partaking of merit, ripening on the side of attachment? Abstinence from false speech, abstinence from malicious speech, abstinence from harsh speech, abstinence from gossip: this is right speech that is affected by taints…on the side of attachment.

“And what, bhikkhus, is right speech that is noble, taintless, supramundane, a factor of the path? The desisting from the four kinds of verbal misconduct, the abstaining, refraining, abstinence from them in one whose mind is noble, whose mind is taintless, who possesses the noble path and is developing the noble path: this is right speech that is noble…a factor of the path.”

—Shakyamuni Buddha

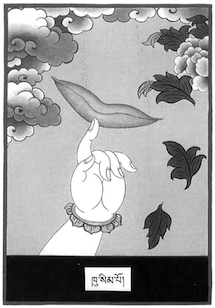

Right Speech from a Tibetan Buddhist Perspective

Rodger Jackson

It is difficult to characterize Tibetan Buddhist views of right speech in a simple manner, but certain points do come up repeatedly in texts, in lectures, and in everyday life. In Tibetan ethics, four acts of speech to be avoided provide a fairly comprehensive definition of nonvirtuous verbal behavior.

Lying, says the influential Indian philosopher Vasubandhu, is discourse in which, knowing one thing to be the case, you assert something else, and your assertion is taken by another person to be the truth. It is the most egregious and universally condemned of the negative acts of speech, because it is deeply subversive of the trust on which human relationships and communities are built.

Slander is speech whose purpose is to incite divisions among people. You tell your friend something about person X or group Y, and whether your words are true or false, or your friend likes Y or doesn’t, if the effect is an increase in his or her hostility toward Y, then slander has occurred. The Gelugpa master Pabongka Rinpoche adds this caveat: “Some people consider doing these things to be a good quality, but they are not. Divisive speech causes great harm, and so can’t be right.”

Abusive speech involves speaking harshly to another being: Addressing someone directly, you either speak in a threatening tone or criticize the other person for real or imagined faults. When the other person’s feelings are hurt by your outburst, the act is complete. Like lying and slander, abusive speech is nonvirtuous because it sows discord between people.

Idle gossip, strictly speaking, is discussion of any topic that is not related to Buddha-dharma. “These days,” Pabongka notes ruefully, “we monks discuss many things when a large group of us gets together in the monastery grounds: the government, China, India, and so on. This is idle gossip.” So, too, are discussions of non-Buddhist treatises. “Idle gossip,” he concludes, “is the least of the ten nonvirtues, but it is the best way to waste our human lives.”

Tibetans and we ourselves may recognize all too much of our verbal behavior in these accounts; the definitions of the vices are clear, and the rationales for their censure understandable. Yet for Tibetans, as for us, a purely behavioral notion of verbal morality leaves certain questions unanswered. What is the status of the white lies that protect or benefit other beings without harming anyone? Is it slander to speak ill of a corrupt employer or a dishonest (or even incompetent) politician? Is it abusive speech to “speak truth to power” or shout at a child about to run into traffic? Is it always idle gossip to discuss the worldly concerns that humans share: politics, art, sports, love, food, or money?

Even the more conservative Nikaya admits that the moral weight of a vice (or virtue) is contingent on the subject object, nature, intention, manner, and frequency of the act. It is worse, for instance, to lie continually to your parents than to gossip idly with your friends just once. Nevertheless, all nonvirtuous behavior is essentially negative and definitely to be avoided.

With the Mahayana and Vajrayana, however, the behavioral ethic of the Nikayas begins to shift toward and ethic of intention. As illustrated by the Lotus Sutra’s parable of the burning house—a wise old man lures his endangered children from a burning house with promises of animal carts he is not going to give them (intending to give them better ones)—a lie may not be nonvirtuous if it is motivated by discerning compassion. Indeed, in Mahayana and Vajrayana, the moral weight of an action comes to inhere primarily in the intention behind it, not the behavior involved. The door is thereby opened to the beneficial lie, the altruistic critique, the expression of righteous anger, and even, perhaps, discussion of topics not overtly related to dharma.

All these are exercises of a bodhisattva’s skillful means. Their acceptance reflects a sophisticated recognition that moral judgments must take intention into account. At the same time, an ethic of intention, too, leaves unanswered questions. If the motive is the only true measure of morality and the thoughts of others are invisible to us, how can we tell that the lie or the slur we just heard was well- or ill-intentioned, permissible or condemned? If we cannot judge others by their behavior, how do we know who among us are the bodhisattvas and who the charlatans? A pure ethic of intention seems as prone to moral relativism as apurely behavioral ethic to superficial legalism.

This may be why, although Tibetan Buddhists consider themselves Mahayanists, and often have held their “crazy” tantric saints in high regard, they tend to fall back on behavioral norms where the motive behind and act remains in doubt. Yes, a true bodhisattva may speak “nonvirtuously” if it serves the spiritual interests of others, but how many true bodhisattvas are there? More to the point: Can you, or I, be so certain that we are bodhisattvas, our motives pure, our discernment sufficient to encompass the situation in which we plan to “speak with skillful means”? Occasionally, perhaps; but most of the time, the answer is no.

Intention does matter, and sometimes we do have both the wisdom and compassion to see that an outwardly “nonvirtuous” act of speech is required, so Tibetan Buddhism does leave the door ajar for the beneficial lie, the appropriate personal or political critique, the relation-building discussion of nondharmic matters. But most Tibetans, whether lama or layperson, would probably agree that, day in and day out, we cannot do better than to model ourselves on the Buddha, striving to speak words that are truthful, conducive to harmony, pleasantly uttered, and about things that, in the final analysis, have the single taste of liberation.

Roger Jackson, Professor of Religion at Carleton College, has published widely on Indian and Tibetan Buddhist philosophy. His most recent book (co-edited with John Makransky) isBuddhist Theology: Critical Reflections by Contemporary Buddhist Scholars (Curzon Press).

Just as there is a “sex industry,” there is also a “lying industry.” Many people have to lie in order to succeed as politicians, or salespersons. A corporate director of communications told me that if he were allowed to tell the truth about his company’s products, people would not buy them. He says positive things about products he knows are not true, and he refrains from speaking about the negative effects of the products. He knows he is lying, and he feels terrible about it. So many people are caught in similar situations. In politics also, people lie to get votes. That is why we can speak of a “lying industry.”

—Thich Nhat Hanh

For a Future to be Possible

Everyday Right Speech

Mudita Nisker

In traditional Buddhist teaching, right speech is one of the steps on the Eightfold Noble Path. Its four guiding principles are:

- Telling the truth

2. Not speaking harshly or cruelly

3. Not engaging in useless speech

4. Not gossiping

When I teach communication skills to individuals, couples and groups, I often suggest these principles as a guide to practicing mindfulness in everyday speech. By keeping the focus on the speaker, they encourage us to look within ourselves rather than to judge others. Following these four simple rules would eliminate much of the conflict, misunderstanding, and hurt feelings that result from careless speech.

I prefer the term skillful speech to right speech. Skillful suggests speech that is acquired through practice. The term right speech is often misunderstood as “I’m right and you’re wrong.” This kind of polarized thinking is exactly the opposite of the spirit of the Buddha’s teaching. Right/wrong arguments harden people’s positions, leading them to lose sight of what is really important to them. I have even heard Buddhist couples argue over which of them was using “right speech,” evidence that when people are caught up in anger even the dharma can be used as a club.

To avoid the polarity of right/wrong speech, I teach the concept of intentional speech – that is, being mindful of one’s purpose in speaking. When people are aware of their intention and express their thoughts and feelings truthfully and with kindness, they are likely to achieve their aim and increase compassionate understanding. When they are unaware of their intention, they are most likely to forget the Buddha’s four principles of right speech and resort to lying or stretching the truth to make a point, shouting hurtful and unnecessary words, and wasting time talking behind each other’s backs.

The discrepancy between how one wants to live one’s life and how one actually lives is particularly distressing to my clients on a Buddhist path who come to me for counseling in my private practice. Like most of us, they find it is easier to behave in accordance with higher principles when they’re alone rather than when they’re with people they live with daily. It is the difficulties of familiar life – petty irritations and ego clashes – that present the greatest tests of our belief and commitment to right speech.

Recently, I worked with a young couple, both serious students of the dharma, who were disturbed to find themselves squabbling over household rules. Neat and orderly surroundings were important to Stacey, and she wanted the dishes washed as soon as they finished eating. Jim (fictional names), on the other hand, often left the dishes in the sink to clean up later. Their arguments over the dishes began to escalate, as evidenced by the following conversation they reported to me:

Stacey: How many times have I asked you not to leave your dishes in the sink? You know I can’t stand to have dirty dishes around. Why do you keep doing this?

Jim: Can’t you see that I’m trying to finish this assignment? Why does everything have to be done according to your time schedule? Doesn’t mine count? Now stop nagging about this.

Stacey: I’m not nagging. I’m telling you that I don’t want to clean up after you.

Jim: When did I ever ask you to do that? I always clean up after myself. The difference is that you’re compulsive about it and I’m not.

Stacey: I can’t talk to you. You discount whatever I say.

Using the four principles of skillful speech as our guide, we can see where Stacey and Jim lost focus of what they wanted to achieve and worked against themselves.

- Telling the truth: Most people believe that they should speak the truth, but which truth? One’s person’s truth is not necessarily the other person’s truth. In this case, Stacey and Jim made the common error of confusing the facts of the situation with their assumptions about the situation. The fact of this situation was the dirty dishes in the sink. What those dishes meant to each one, however, was open to interpretation. Stacey assumed that Jim’s leaving the dishes in the sink meant that Jim expected her to clean up after him. Moreover, when he didn’t do it, she assumed he dismissed her wishes. Jim reacted to her assumption with one of his own: that Stacey was compulsive.

Many disagreements result from people being unaware of the other person’s assumptions and often of their own as well. Articulating assumptions illuminates each person’s truth, allowing them to separate fact from assumption. Once Stacey and Jim learned to be mindful of these distinctions, they were able to think about how to resolve their disagreement.

- Not speaking harshly: When people are in conflict, they often express their anger or annoyance by making sweeping accusations or trading insults, as Stacey and Jim did. Learning to express themselves clearly and firmly, however, they were able to resolve the situation swiftly.

Stacey: Would you mind rinsing the breakfast dishes in the sink and putting them in the dishwasher?

Jim: I’ll do it in a little while.

Stacey: I’d appreciate your doing it now. Looking at them really bothers me.

Jim: I’m right in the middle of something. If it’s bothering you, maybe you can wash them now, and I’ll do the dinner dishes.

In this dialogue, Stacey and Jim stated clearly and truthfully what they wanted without insulting each other. Stacey expressed what bothered her and Jim responded in a way that showed he respected her feelings and that he did not expect her to clean up after him.

- Useless speech: When we are mindful of our intentions, we are less likely to engage in useless speech. Some individuals, for example, feel compelled to blurt out their anger whenever they are upset. Later, after the dust settles, they may see the situation differently and regret what they said. In my communication work, I ask clients if anyone consistently displayed angry behavior when they were growing up. Typically, it is a parent, and I suggest tongue-in-cheek that they may be channeling him or her. This suggestion often helps clients understand that their behavior demonstrates their conditioning more than their choice.

Changing behavior requires self-awareness. I encourage my clients to pause when they recognize an angry thought and to ask themselves: Will expressing this thought be useful? Will it help me achieve the outcome that I want?

- Not gossiping: Gossip is often untrue, cruel, and useless, and those who follow the Buddha’s first three principles of right speech would find little to gossip about. I emphasize intention as the overriding principle of skillful speech and self-questioning as the means by which we can test our intention. For example, when we repeat unflattering information about others, is our intention to discredit them or make them appear foolish? Do we want to make ourselves look good and them bad?

Inseparable from right speech is good listening. When we talk without hearing the other person, we are engaged in a monologue, not a dialogue. Staying open to others’ thoughts and feelings enhances understanding and harmony. The more skillfully we speak and listen, the more skillfully we live our lives. And the more we can bring the teachings of the Buddha into the world through our words.

Right Speech, or sammavacha, is the third step of the Eightfold Path, which is the fourth and last Noble Truth preached by Shakyamuni Buddha. The following is a collection of classic and contemporary views of Right Speech.

Sex, Lies, and Videotape

Donald S, Lopez, Jr.

The recent travails of our president have provided numerous occasions for Buddhist reflection. His ruminations on “what the meaning of ‘is’ is” during his grand jury testimony, for example, were worthy of the great Middle Way philosopher Nagarjuna. But the overriding impression from the entire affair has been to confirm the Buddha’s insight that desire, hatred, and ignorance are indeed poisons. These three poisons are said to motivate ten types of nonvirtuous deeds, which in turn cause all the sufferings of the universe. They are killing, stealing, sexual misconduct, lying, divisive speech, harsh speech, senseless speech, covetousness, harmful intent, and wrong view. All ten (if we include the alleged murder of Vincent Foster) have afflicted the nation of the course of the independent counsel’s investigation.

The President, his critics charge, has been most guilty of lying and sexual misconduct. According to Buddhist ethical treatises, lying is a verbal misdeed in which the speaker says something different from what he or she knows to be the case, and the listener understands what the speaker says. In a qualification that seems particularly appropriate to the recent scandal, if the listener does not understand what the speaker has intended, it is not a lie, but merely senseless speech. Three levels of lies are enumerated. The gravest is to falsely claim spiritual achievements. The second is falsehood that brings great benefit to oneself and others. The third is a slight lie that brings neither help nor harm. The House Judiciary Committee has to determine which of these are high crimes and misdemeanors. In the Mahayana, the question of lying is revisited in the context of the Buddha’s skillful means. Did the Buddha lie when he said that there are three vehicles, when he knew, in fact, that there is only one, the Great Vehicle that will take all beings to Buddhahood?

Most of the discourse surrounding the scandal, however, has dwelled on lesser questions, notably, the definition of sex. And on this point, Buddhist texts are hardly silent. The great fourth-century compendium of Buddhist doctrine, Vasubandhu’s Treasury of Knowledge(Abhidharmakosha), explains that sexual misconduct is censured in the world because “ it is the corruption of another man’s wife and because it leads to retribution in a painful rebirth.” His definition of sex is far more laconic than that of Paula Jones’s lawyers; Vasubandhu says that “the deed of improper desire is to go where one should not go.” He goes on to describe four kinds of sexual misconduct. The first is sexual intercourse with an improper partner, such as another man’s wife, one’s mother, one’s daughter, a nun, or a female relative up to seven times removed. In keeping with the misogyny so prevalent in Buddhism, it is noteworthy that sexual misconduct is defined from the male perspective, prohibiting intercourse with women who are somehow off limits, protected by a husband, a family, the sangha, or the incest taboo. The texts make no mention of White House interns.

The other types of sexual misconduct involve a man’s intercourse with is own wife, but in ways that are somehow improper. Thus, to use “a path other than the vagina” is to commit sexual misconduct. The President may have a problem here. The sex act also becomes a misdeed if it is performed in an unsuitable location, such as a public place, near a stupa, in a forest retreat, or in the presence of images of the Three Jewels. No mention is made of the Oval Office. Finally, there are unsuitable times for sex, such as when one’s wife is pregnant, nursing, ill, menstruating, or during the day.

But what if the woman is unmarried? It all depends on whether the woman is some other man’s property. Vasubandhu explains that “intercourse with a young girl is illicit with regard to the man to whom she is engaged, and, if she is not engaged, with regard to her guardian; if she has no guardian, then with regard to the king.” He does not mention whether it is illicit when the man engaging in intercourse with a young girl is the king.

The President denied a sexual relationship on two grounds, first, because there was no genital intercourse, and second, because he maintained that there was no orgasm. He might take initial comfort from the fact that some texts define the act as having occurred only upon “the contact of the two organs.” But the commentaries make clear that the term organ in this context includes, by extension, the other two female orifices. Nor is the President saved by the fact that, in most cases, he did not ejaculate, for sexual misconduct is said to occur when the penis is inserted “even as much as a sesame seed” into the female. Besides, as the stain on the dress proved, the President did ejaculate. One of the few defenses that the President did not make in his deposition was to claim to be a bodhisattva, who vows to be willing to engage in lying and sexual misconduct whenever necessary to benefit sentient beings. But he seems to lack such motivation. If only the President had been a god in the Heaven of the Thirty-Three rather than a more mundane deity, he might have gotten away with it, for there, when gods make love, the males emit not semen, but wind.

Donald S. Lopez, Jr., is a contributing editor to Tricycle and Professor of Buddhist and Tibetan studies at the University of Michigan. His most recent book is Prisoners of Shangri-La: Tibetan Buddhism and the West (University of Chicago Press).

More people get hurt by gossip than by guns.

—Robert Aitken, The Practice of Perfection

From the habit of speaking truthfully confidence is acquired, since there is no need then to dissemble or conceal the truth. Moreover, the speaker of truth inspires confidence in others who come to know that they may rely implicitly on his words.

—Hammalawa Saddatissa, Buddhist Ethics

Out of not lying we can develop our voice to speak for compassion, understanding, and justice.

—Jack Kornfield, A Path with Heart

Think of this simple instruction: What would it take to be able to communicate with my enemy…to have my enemy hear what I’m trying to say, and what would it take to be able for me to hear what he or she is trying to say to me?

—Pema Chodron, Start Where You Are

Certain silences don’t help, they hurt. It’s important to tell your story. We call it talking meditation.

—Bernie Glassman Roshi, Bearing Witness

Right Speech in Marriage

Susan Piver Browne

I love the concept of idiot compassion. Just as being truly compassionate doesn’t mean always being sweet and nice (sometimes it means being cold, harsh), being truly honest doesn’t mean speaking your thoughts and feelings as they arise. Other awarenesses and intention must be at work—and a recognition that the truth is not solid. This is especially so in a marriage, where speech can so easily be used against one’s partner—or against the world, from the security and privacy of the bedroom.

Avoid Lying

What is abstaining from lying in marriage? If idiot compassion is true compassion’s lobotomized cousin, so idiot honesty is cousin to true honesty. Abstaining from lying doesn’t mean speaking your thoughts and impulses as they arise; it means being aware of the presence of certain feelings in yourself, your beloved, and the space you occupy. In the Taoist sense, being in this flow can cue you about when and how to speak skillfully, with as few or as many qualities as possible. In this sense, telling the truth requires such precise awareness.

When you know the truth, it may not be so hard: It’s then a matter of fortitude, and of choice. It’s not so easy when the truth is not perceptible. The truth shifts—frailty, courage, loveliness, and stupidity are in every moment. As such, there may be only pretending to know something about the truth—even trusting that there is no truth. Therefore the injunction—not to tell the truth—but to avoid lying.

At the same time, to be in an impassioned relationship, the truth must speak. It’s my experience that there is tremendous synchronicity between truth and passion. Desire flourishes on the edge. Its opposite is rest. Truth—trying for truth of self, of other, of the moment—means working with the edge. For those who are inspired by passion, it means staying alive on the deepest levels.

Avoid Abusive Words

I’ve known people who hurl epithets and use insults and aggression to make a point, to clear space, to be heard. My family didn’t do that. It’s easy for me not to do those things with my husband, no matter how provoked. What my family did do—and what it’s hard for me not to do—was create abusive silence. There is the silence of refraining from saying something hurtful out of a sense of gentleness. And there is the silence of fuck you. Is this abusive speech? I think so.

Avoid Idle Chatter, Slander

I immediately think of jealous territoriality, of clearing space around oneself as a way of preventing the closeness of others who may threaten the couple—very female. The lover has the ear of the beloved in a very special way. No matter what front is presented to the world, married couples, it seems, have intimate, before-bed moments of conversation about work, the car, and other people, whatever. In these moments it is so easy to influence the beloved’s responses with tiny remarks: “He is just after money,” “I think she may not like her job.” This quiet creation of one viewpoint of people and events must be approached with great care and without the intention of dividing the beloved from his own thoughts, his own approach, out of fear.

On the other hand, one of the great joys of marriage is the dissection of thoughts and responses deemed too small or intimate for others to hear or for which only the beloved understands the context: “Her haircut made me think of that lampshade at your mother’s house.” Sharing that intimacy, a history spiced by a tiny (or enormous) dram of laughing together at someone else, provides a strange, uneasy comfort. But no one is to be used as a tool for our own comfort, without regard for their humanity.

Avoid Gossip

It’s painful to learn that holding a mutual thought about someone else, no matter how small, can be a tremendous unkindness.

Once, I was the victim of gossip so horrible and strong that I almost believed it myself. It had such life that I spent a lot of time examining my circumstances to see if it might not be true. The experience really sucked. Eventually, I realized that its genesis was attributed to just such tiny remarks blended and compounded. Some extant energy met the force of unkindness and combined to create a very painful situation. I vowed never to gossip again. And, with some notable failures, I’ve pretty much stuck to this. When my beloved gossips to me, I hear and try not to respond or add to it. I try and make some genuine remark that could recontextualize the person’s actions or vibration in a more benign light. When I am compelled to gossip, I try to prevent myself. It is hardest of all with my husband. I want the moronic pleasure of maliciousness and high-toned judgment of others, with the one who holds me in the highest regard. The S&M of ego.

In the end, for me, it boils down to something a wonderful friend once told me: If the intention is good, then it doesn’t matter if the result manifests in the heaven or hell realm.

Susan Piver Browne is writing The Hard Questions: A Lover’s Guide to Passion and Commitment, to be published by Tarcher/Putnam this year.

Words from the Heart

Steven Smith and Mirabai Bush

The cutting edge of American dharma is challenged with the task of transmitting a 2,500-year-old Buddhist lineage into modern culture. As the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society, we have sponsored insight meditation (vipassana) retreats for various sectors of American society including business, academia, philanthropy, and media. We look for direct, honest language that will speak to a public wary of things esoteric, Eastern, and religious.

When we talk about contemplation in business, for instance, we talk about seeing interrelationships rather than linear chains. We explain that deep practice frees you from the tyranny of linear cause and effect and that understanding the mystery of how things actually happen—how any act can change the direction or quality or outcome in a profound way—increases one’s leverage.

Two and a half years ago, the CEO and fifteen top executives of a major global corporation sat a silent mindfulness retreat. Some were resistant to the intimidation of silence, and others kept striving for some tangible result. We used sitting, walking, and lovingkindness meditations to introduce the precepts as ways to create a safe space of “non-harming” and life stories and Jataka tales to illustrate the principles. In the end, participants had taken up the challenge and turned their potent left-brain focus inward, into the moment. Most of the executives continue to practice today, including the CEO.

Now, many retreats and dharma tales later, the corporation encourages new participants to attend retreats with literatures that speaks of “Mindfulness as a tool that will allow you to purposefully respond rather than just react to change. When practices regularly, Mindfulness provides a variety of personal and organizational benefits, which include increased adaptability, nonjudgmental listening, enhanced clarity and creativity, and greater integration of your personal and professional life.”

In retreats it is essential to respect and listen to where people are, to speak from the heart, and to understand that even terms like awareness and lovingkindness need to be defined and explained. Sometimes we use clusters of poetic terms to convey deeper meaning. For national environmental leaders, we talked about introducing them to a spiritual habitat, a familiar notion to them.

With members of the media, we suggested that meditation practice is a kind of inner journalism: seeing and reporting things as they are. We talked about right speech—that what you report should not only be true but timely and useful. After the retreat, one journalist told us, “Compassion in journalism—maybe that is the same thing as fairness and accuracy.”

In working with mainstream practitioners, articulating the practice of nonharming or compassion is at once sobering and soothing. Simple language connects people to the fragility and strength of the human heart, and because skillful speech rests in the intention of the speaker, it is not so much the words as the tone that conveys the power of nonharming teachings. In fact, teaching dharma to mainstream groups differs little in spirit from teaching traditional vipassana retreats. How the timeless teachings are elucidated makes the difference between awakening dharma within someone or creating confusion.

Steven Smith is a Guiding Teacher at the Insight Meditation Society in Barre, Massachusetts, the Kyaswa Valley Retreat Center in Burma, and the Blue Mountain Meditation Center in Australia. He is a founder of Vipassana Hawai’I and the MettaDana Project in Burma and a senior advisor to the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society (CMIS).

Mirabai Bush is Director of CMIS. For ten years, she directed the Seva Foundation Guatemala Project and is co-author with Ram Das of Compassion in Action: Setting Out on the Path of Service.

Religious conversation or truthfulness alone is not right speech. Abstinence from unwholesome speech is the essence of right speech. It should be noted that when occasion arises for one to speak falsely, to slander, to use abusive language, or chatter uselessly, if one restrains oneself from doing so, one is establishing the practice of right speech. Indeed, one who refrains from false speech will engage only in speech which is truthful, gentle, and beneficial and will promote harmony. The essential point is that one who abstains from wrong speech establishes the moral foundation of the path.

—Dr. Rewata Dhamma,

The First Discourse of the Buddha

“Don’t talk about injured limbs.” In other words, don’t talk about other people’s defects.

—Pema Chodron, Start Where You Are

The four nonvirtues of speech include (1) lying, the worst lie being that one has spiritual realization; (2) slander, which involves using speech to separate close friends, the worst case being that of slandering members of one’s spiritual group; (3) harsh speech that hurts others; and (4) gossip or useless speech, which wastes one’s own and others’ time.

—Chagdud Tulku, Gates to Buddhist Practice

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.