What are some important texts in Zen Buddhism?

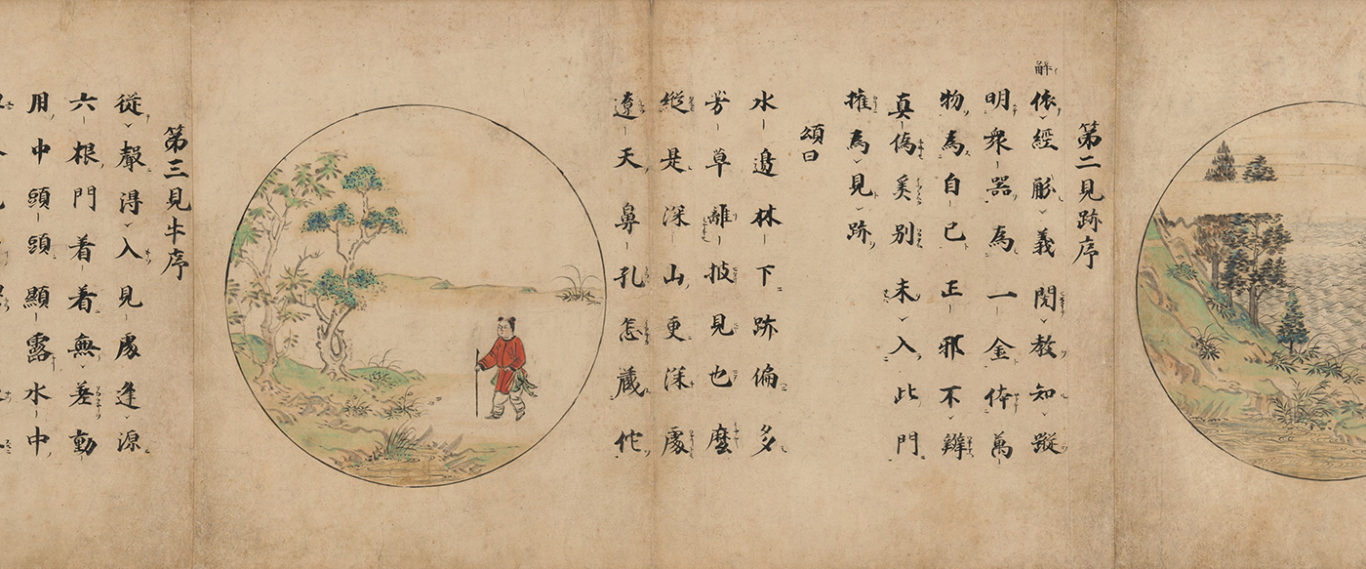

In The Ten Verses on Oxherding, a famous Zen parable, a young oxherder finds and trains a lost ox, representing the search for enlightenment. This 13th-century handscroll is the oldest known Japanese illustrated copy of the Ten Verses on Oxherding. | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, 2015.

At times, Zen has distinguished itself from other Buddhist schools by claiming that one can attain enlightenment without reading Buddhist texts—what is known as “direct transmission outside the scriptures.” However, while Zen insists that true understanding cannot be grasped through language, there is, in fact, a vast body of Zen literature. Indeed, nearly every major figure in Zen has had a deep and wide-ranging knowledge of the sutras (scriptures), commentaries, and history of Buddhism.

Early Zen was deeply influenced by several of the Mahayana (“Great Vehicle”) sutras that emerged in the early 1st millennium CE. Among these are the Lankavatara Sutra, which contains teachings on the nature of consciousness; the Avatamsaka Sutra, which describes how all things and beings are interdependent; and the Vimalakirti Sutra, which addresses the illusory nature of appearances and the concept of nonduality, the idea that an understanding of existence is incomplete if one views the world according to rigid dichotomies. In the 8th century CE, the Diamond Sutra, which presents Madhyamaka, or Middle Way teachings, emerged as the foremost sutra of the Zen school and arguably has remained so since. The brief, closely related Heart Sutra―said to be a distillation of the Diamond Sutra―is chanted daily in most Zen temples.

One of the most important texts of Zen history, the Platform Sutra, is not a sutra in the standard sense of the word. It was composed as a record of talks given by Huineng (638–713), the Sixth Ancestor of Zen. However, scholars believe the original version was not composed until sometime after 780, and some details in it are contradicted by historical records. Even so, it is a treasure of Zen teachings on enlightenment.

During the Song dynasty (960–1279), Zen teachers in China compiled collections of gong’an (Jp., koan) stories, brief anecdotes that point to an aspect of enlightenment. In time, other teachers added footnotes, pointers, verses, and commentaries to the original stories. These became the classic koan collections still used as subjects for dharma talks and meditation. The most significant of these are the Blue Cliff Record, the Book of Serenity (or Equanimity), and The Gateless Barrier (or Gateless Gate).

Song-dynasty Zen also produced many “extensive record” [outside traditional Buddhist scripture] and “lamp record” [lives and teachings] texts that preserved biographies of important teachers, along with sermons, poems, lineage charts, and anecdotes. Most of what we know about early Zen teachers comes from these records.

As Chan (Jp., Zen) spread to the Korean Peninsula, Vietnam, and Japan, teachers in those countries made significant contributions to Zen literature. Prominent among these are a collection of commentaries on the Diamond Sutra by the Korean Zen monk Gihwa (1376–1433) and Vietnamese lamp records. Well-known Japanese texts include the Kana Shobogenzo (or just Shobogenzo), a collection of essays by Eihei Dogen (1200–1253), founder of the Soto school, and the autobiography Wild Ivy and other works by Hakuin Ekaku (1686–1769).

Tricycle is more than a magazine

Gain access to the best in sprititual film, our growing collection of e-books, and monthly talks, plus our 25-year archive

Subscribe now