The Journey of Buddhism

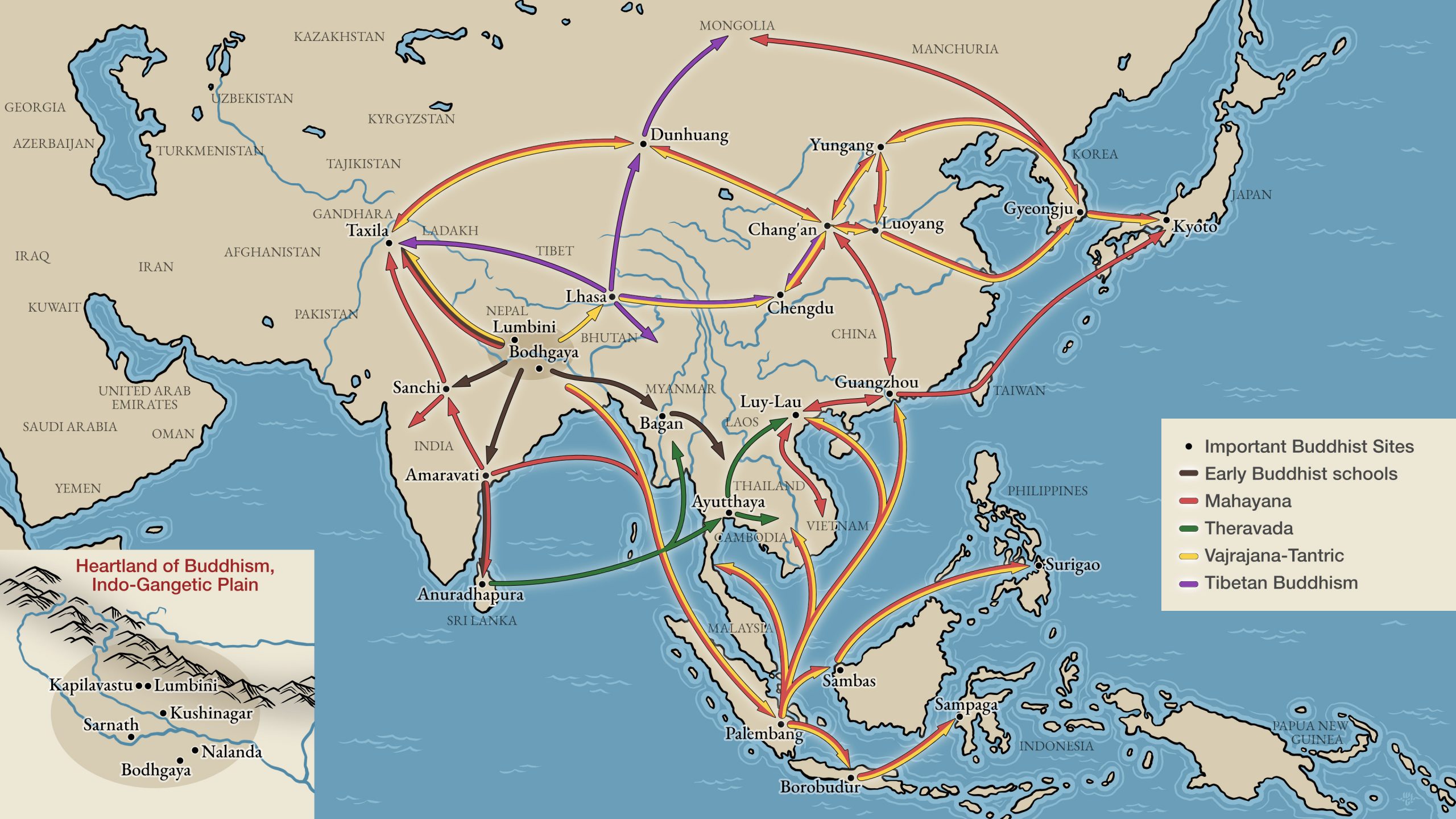

Approximately 2,500 years ago, the Buddha lived and taught on the Gangetic Plain, near the border between present-day Nepal and India. Within a few centuries, his teachings had traveled far beyond his homeland. Buddhism spread along trade routes, across seas, and over mountains and deserts, carried by monastics, merchants, and ruling families. Tower stupas, cave temples filled with murals, and other sacred sites still stand along ancient trade routes, and each region reshaped the tradition in its own language, myths, and customs. Over time, Buddhism spread to nearly every part of Asia, and in the modern era, it has become a global phenomenon. This page outlines the trajectory of the tradition, explaining how Buddhism moved, adapted, and became one of the world’s major religions.

Table of contents

- How Buddhism Spread

- Early Buddhism

- Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia

- The Silk Road and Central Asia

- East Asia: China

- East Asia: Vietnam, Korea, and Japan

- Tibet and the Himalayan Region

- Mongolia and the Steppe Empires

- Europe and the Americas

- New Buddhist Movements

- Pilgrimage and the Circulation of Practice

- The Global Present and the Future of Buddhism

How Buddhism Spread

Buddhist ideas and practices didn’t spread in a single direction or uniform way. From their origins in India, the teachings moved along many routes, shaped by local needs and historical conditions. Traditional histories often highlight a single monk or key lay figure delivering the teachings from one land to another, but the reality was far more complex. Many factors were involved in carrying Buddhism into new lands and cultures.

Trade networks were among the most important. Merchants traveling between rural outposts, cities, and empires carried goods, texts, stories, and images. Monastics joined caravans, bringing practices and scholastic training. Monasteries along trade routes offered travelers lodging, prayer, and a place to exchange goods. These mercantile ties linked Buddhist communities to the broader circulation of commerce and culture.

Political support also played a decisive role. Emperors, kings, and aristocrats patronized monasteries, sponsored scripture translations, and built monuments that drew pilgrims. Elite support gave Buddhist communities resources and protection, allowing them to take root. As a religion of learning and philosophical inquiry, Buddhism often first spread among educated circles. Rulers saw it as a way to strengthen authority, unite diverse populations, and connect to global networks. Buddhist emissaries became a feature of premodern diplomacy.

Laypeople were equally vital. Householders gave shelter, food, and clothing to monastics and brought practices into daily life. Families passed down narratives and ties to local temples and monasteries, sometimes sending their children to train as monastics. Whenever royal patronage declined, lay communities preserved traditions that might otherwise have disappeared. Migrant groups also carried teachings to their new homelands.

In the modern era, increased literacy, the publishing of texts and translations, the role of lay teachers, and digital media have created new channels of transmission. Global travel and communication have made Buddhism an international tradition, while pilgrimage sites in India have become destinations for worship and tourism, amplified by millions of social media posts.

Buddhism has witnessed the rise and fall of numerous movements and schools, and its spread has always been dynamic and adaptive, shaped by trade, the shifting fortunes of political power, and the devotion of ordinary people.

Early Buddhism

After the Buddha’s awakening, followers gathered around him and carried his message to neighboring towns and villages. He urged them to share his teaching—the dharma—wherever they went and in local dialects, setting Buddhism on a missionizing path from the start. Monastics traveled on foot, living on alms and depending on the goodwill of householders, as the Buddha himself had done.

Buddhist scriptures such as the Pali Mahaparinibbana Sutta identify four places of special significance: Lumbini, his birthplace; Bodhgaya, the site of his enlightenment under the Bodhi tree; Sarnath, where he first taught the dharma; and Kusinagara, where he died. Monasteries and shrines soon emerged around these sacred sites, drawing a steady stream of travelers and helping the teachings spread beyond the earliest communities.

Buddhism flourished in regions linked to trade and expanding cities. Merchants and elites supported monasteries, which offered lodging and gathering places for travelers. These factors tied Buddhism to urban life, and wealth from cities sponsored early complexes such as Amaravati in the south, which became centers of devotion, learning, and pilgrimage.

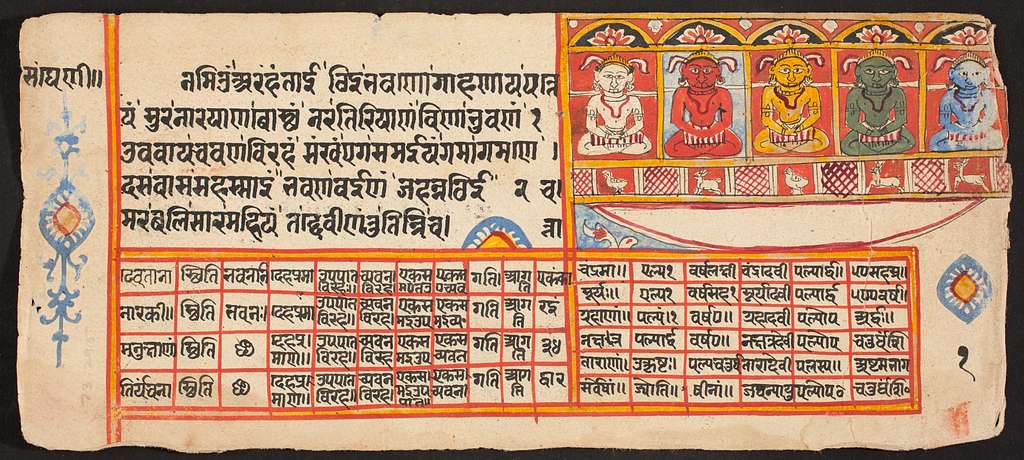

As the sangha grew after the Buddha’s death, councils gathered to organize and authenticate the various oral teachings, which were later compiled into the first canons. Monastic rules were codified, giving institutions stability and authority. The sangha eventually split into multiple schools, each interpreting the teachings differently. These groups traveled in different directions, establishing centers and lineages that gave Buddhism a diverse character from an early stage.

The Mauryan dynasty (ca. 320–185 BCE) was the first major political force to give the movement powerful support. Based in the Magadha homeland, Emperor Ashoka (ca. 304–232 BCE) embraced Buddhism and made it part of his rule. His stone edicts, many still standing, proclaimed his vision of the Buddha’s teaching throughout his empire. He also commissioned stupas and monasteries, increasing the sangha’s visibility and resources. Ashokan missions carried early Buddhism throughout the Indian subcontinent and beyond.

In the northwest of the Indian subcontinent, Gandhara became a thriving hub, where art, texts, and new ideas flourished. Along with centers in the south, these enclaves became stepping stones for Buddhism’s expansion across Asia.

Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia

Tradition holds that Buddhism reached Sri Lanka in the 3rd century BCE. The son of Emperor Ashoka, a monk named Mahinda, is said to have converted King Devanampiya Tissa after a meeting in a royal garden. Soon after, Ashoka’s daughter, Sanghamitta, brought a branch of the Bodhi tree from Bodhgaya, under which the Buddha became enlightened. Planted at Anuradhapura, it became a major pilgrimage site.

These stories mark Sri Lanka as an early Buddhist center. With royal support, monasteries were built, and in the 1st century BCE, the island preserved the oral teachings in writing, compiling them into the Pali canon. Recording the scriptures gave the sangha a stable foundation and extended Sri Lanka’s scholastic influence abroad. Over time, Sri Lankan Buddhism developed its own identity. What is now known as Theravada Buddhism clearly took shape on this foundation in the 5th century CE with the works of the scholar-monk Buddhaghosa.

From Sri Lanka and South Asia, Buddhism spread into Southeast Asia. Rulers in the regions now known as Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Malaysia, and Indonesia adopted Buddhism between the early centuries CE and the first millennium, using it to consolidate their kingdoms and connect with trade networks. From the 11th to the 13th centuries, Theravada Buddhism became dominant in Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos, strengthened by close ties with Sri Lanka. Buddhism in Malaysia, Indonesia, and other islands in the archipelago declined in the 15th and 16th centuries as Islam rose.

In Theravada countries, local devotional forms deepened Buddhism’s roots. In Sri Lanka, the Buddha’s tooth relic became a major pilgrimage site and was closely tied to royal authority, with kings claiming the right to rule by protecting it. In Southeast Asia, temples and stupas stood at the heart of community life, supported by lay families and wealthy merchants.

Sri Lanka and mainland Southeast Asia remain powerful centers of Buddhism, shaping its development and sustaining its status as the region’s dominant religious tradition.

The Silk Road and Central Asia

From the 3rd century BCE onward, Buddhism spread into Central Asia along the caravan routes later known as the Silk Road. Merchants, monks, and pilgrims traveled across deserts and mountains, establishing monasteries and temples in oasis towns that anchored the religion’s growth. Monumental cave complexes such as the Mogao Caves at Dunhuang, the Kizil Caves, and the Bezeklik Caves became important centers, leaving some of the most vivid records of Buddhism’s spread along these routes. These Central Asian networks carried teachings, art, and rituals from India to Persia, China, Korea, and even to Egypt and Rome.

Gandhara, in today’s northern Pakistan and Afghanistan, was one of the earliest strongholds. Buddhism was established there by the 3rd century BCE, and under the Kushan Empire (ca. 30–375 CE) it became a thriving center of Buddhist culture. For a brief period, Alexander the Great’s Macedonian Empire (336–323 BCE) controlled parts of Gandhara, bringing Buddhism into contact with Hellenistic ideas. Gandhara’s monasteries produced some of the earliest surviving texts, trained monastics, and created some of the first human images of the Buddha. These innovations traveled with merchants and pilgrims into Central Asia and beyond, helping spread a new vision of the Buddhist tradition.

By the 1st to 3rd centuries CE, many of the scriptures moving along these routes were Mahayana texts. As they reached Central Asia and were translated into local languages, they prepared the ground for Mahayana to become the dominant form in Central and East Asia. Stories of royal conversions, miraculous relics, and the protective power of texts further encouraged patronage, securing Buddhism in new regions.

Later, the Uyghur kingdoms (9th to 11th centuries) gave another wave of support. Ruling the Tarim Basin north of Tibet, their elites sponsored monasteries, cave temples, and translation projects that kept Buddhism thriving in Central Asia even after it began to decline in India. Uyghur scribes and translators played a key role in transmitting texts, art, and ritual practices into East and Northeast Asia.

By the time Buddhism spread more widely in East Asia, it had already undergone centuries of adaptation in India and Central Asia.

East Asia: China

Buddhism entered China in the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, transported by caravans from Central Asia and ships docking in southern ports such as Guangzhou. Monks, merchants, and travelers brought scriptures, relics, and practices by land and sea.

One of the earliest and most important figures was An Shigao (ca. 148–180 CE), an Iranian prince of the Parthian Empire (247 BCE to 224 CE) who became a monk and arrived in Luoyang, an imperial capital and eastern terminus of the Silk Road, in the mid-2nd century CE. He translated meditation manuals and early sutras into Chinese, marking the beginning of a lasting Buddhist presence.

By the 3rd and 4th centuries, Buddhist communities had established themselves in cities along the Silk Road. Central Asian monks transmitted Mahayana texts and practices, while royal and elite patronage supported translation efforts and the construction of monasteries. Among the most influential translators was Kumarajiva (344–413 CE), a scholar-monk from Central Asia who settled in Chang’an (modern Xi’an) in the early 5th century. Known for his language skills, he and his team translated numerous key Mahayana scriptures, helping to shape the vocabulary and style of East Asian Buddhism.

Chinese monks also went abroad in search of teachings. Faxian (ca. 337–422 CE), Xuanzang (602–664), and Yijing (635–713) journeyed to India and Central Asia by land and sea, returning with texts, relics, and detailed records of Buddhist practices. Their travels created a two-way flow of ideas linking China with the wider Buddhist world.

Chinese dynasties became home to many strands of Buddhism. Early Indian schools, Mahayana scriptures, and, later, esoteric and tantric practices all took root. By the 6th century, Buddhism was firmly established in the Chinese heartland. Dynastic rulers patronized monasteries and sponsored monumental cave temples, such as the Yungang and Longmen Grottoes, which became centers of art, worship, and pilgrimage.

The Chinese Buddhist canon, compiled over centuries, preserves a vast body of material, including early texts that would otherwise be lost. With the development of woodblock printing between the 7th and 10th centuries, scriptures could be reproduced in large numbers, making them widely available to monasteries and the educated elite. A 9th-century Chinese printed copy of the Diamond Sutra is widely considered the oldest known dated book in the world.

China also became a center of innovation, giving rise to unique esoteric and scholastic schools. Over time, Buddhism also interacted with Confucian and Daoist thought, shaping its practices and philosophy in distinctive ways. Most notably, Chan originated in China and later spread to Vietnam, Korea, Japan, and beyond. Today, these meditation schools are popularly known in the West as Zen, although each tradition has distinct practices and teachings

East Asia: Vietnam, Korea, and Japan

Carried by maritime trade from India and Southeast Asia, early strands of Buddhism reached Vietnam by the 2nd century CE. Traditional accounts say monks arrived by sea and established temples at Luy Lau, near modern Hanoi, one of the first centers of Buddhism in East Asia. Later interactions with Chinese dynasties brought an influx of Mahayana scriptures and practices. Vietnamese Buddhism also blended with Confucian, Daoist, and indigenous traditions. During the colonial era and into the 20th century, Buddhism became a key source of identity and resistance, ensuring its survival.

In Korea, Buddhism arrived from China in the 4th century CE. A monk sent by the Qin kingdom officially introduced it to Goguryeo (37 BCE–668 CE) in 372 CE, followed soon after by Baekje (18 BCE–660 CE) and Silla (57 BCE–935 CE). During the Goryeo dynasty (918–1392) Buddhism reached its peak. Royal patronage funded monasteries, rituals, and monumental projects, including the Tripitaka Koreana, carved onto more than 80,000 wooden blocks. With the rise of the Joseon dynasty (1392–1910), Confucianism became the state ideology, and bureaucrats stripped Buddhism of its royal patronage. Yet monastic communities, ensconced in deep mountain valleys, and lay devotion kept it alive.

Japan first received Buddhism in the mid-6th century CE. According to tradition, the king of Baekje sent a statue of the Buddha and scriptures to the Yamato court around 552 CE as a diplomatic gift. Buddhism soon gained royal support, most notably from Prince Shotoku (574–622), who built some of Japan’s earliest temples. In later centuries, Buddhism became integral to Japanese culture, influencing art, literature, and politics. But it also faced challenges, such as during the Meiji era (1868–1912), when the state elevated Shinto and stripped Buddhism of land and privileges. At the height of the Japanese Empire (1868–1947), sacred temple objects were melted down to supply its war effort. But Buddhism endured, and Japanese schools such as Zen, Nichiren, and Pure Land went on to spread worldwide.

Although each country followed its own path, all three—Vietnam, Korea, and Japan—adopted Buddhism through a combination of myth, royal patronage, and local adaptation. Despite periods of repression, Buddhism remained a shared religious tradition and a channel for cultural exchange across East Asia.

Tibet and the Himalayan Region

Buddhism reached Tibet later than it did in other parts of Asia. While Buddhist influences from India, China, and Central Asia appeared earlier, a lasting presence was established in the 7th century CE, when King Songtsen Gampo (605–650) married princesses from Nepal and China. They brought Buddhist texts and statues as dowry gifts, giving Buddhism a foothold at court even as indigenous shamanic traditions remained strong.

In the 8th century, King Trisong Detsen (742–797) invited Indian teachers to Tibet, most famously the philosopher Shantarakshita (725–788) and the Vajrayana master Padmasambhava (ca. 8th century). Padmasambhava became a legendary figure, credited with taming local spirits and incorporating them into Buddhist cosmology, clearing the way for the construction of Samye, Tibet’s first monastery. Shantarakshita trained the earliest generation of monastics, many of whom helped translate foundational texts into Tibetan.

In the mid-9th century, the Tibetan Empire and its monasteries collapsed, ushering in about 150 years of political fragmentation. Revival efforts began in the 11th century, when the Indian Vajrayana teacher Atisha (982–1054) was invited to Tibet. His influence helped launch a resurgence that led to the formation of new schools. Over time, the Nyingma, Kagyu, Sakya, and Gelug lineages emerged, each tracing authority to translation projects and Vajrayana teachers from India. Monasteries tied to these schools became powerful centers of learning, ritual, and authority.

Buddhism also spread into Bhutan, Sikkim, Ladakh, and Nepal, where it blended with local traditions to create distinctive Himalayan forms. In the Kathmandu Valley, Newar Buddhism preserved older Vajrayana practices that shaped the region. Royal and elite families sponsored monasteries, invited teachers, and used Buddhism to reinforce their authority, while lay communities supported institutions through pilgrimage, offerings, and devotion to charismatic lamas and tulkus.

By the 15th century, the forms of Tibetan Buddhism we know today dominated the plateau and much of the Himalayas, extending their influence into Central Asia, Mongolia, Manchuria, and northern China. The 20th century, however, brought dramatic changes. After the Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1959, tens of thousands of Tibetans fled into exile, carrying their traditions abroad. This diaspora became a pivotal moment in the global spread of the Tibetan Buddhist tradition.

Mongolia and the Steppe Empires

In Northeast Asia, Buddhism spread through Manchuria (present-day northeastern China) and Mongolia along trade routes that linked China, Korea, and Central Asia. These areas influenced one another through commerce and diplomacy, as courts used Buddhist institutions for governance and merchants and monks carried teachings across the steppe. Korean-Manchurian channels also connected the region to maritime routes and Japan, creating a web of exchange that shaped how Buddhism took root in the northeast.

The Balhae (696–926) ruled a large state in present-day North Korea and eastern Manchuria. Archaeological finds reveal numerous temples and artifacts, indicating that Buddhism was well established there through ties with the Tang dynasty, the Korean kingdom of Silla, and Japan.

In the 12th century, the Jurchens, a people from central Manchuria, founded the Jin dynasty (1115–1234), ruling over their homeland and parts of northern China. They drew on Buddhist networks from neighboring regions and sponsored monasteries, temples, and grotto projects. Their government regulated the sangha and used patronage to shape ritual practices.

The Mongols made Buddhism a dominant force across Inner Asia in the 13th–14th centuries. Kublai Khan (1215–1294) established the Yuan dynasty and elevated Buddhism, particularly the Tibetan Sakya school. He created an agency to oversee monasteries throughout his empire, which spanned much of Central and East Asia. He relied on Tibetan lamas as advisors and facilitated the movement of teachers, texts, and art through Mongolia, Manchuria, and northern China.

Developments in these regions were connected with the Korean peninsula. From Goguryeo (37 BCE–668 CE) and Balhae (698–926) through the vibrant Buddhist kingdom of Goryeo (918–1392), Korean courts exchanged monks, texts, and emissaries with Manchurian and Mongol neighbors, allowing ideas and images to circulate in the northeastern steppe grasslands.

In the 17th century, Jurchen descendants—the Manchus—overthrew the Chinese Ming dynasty (1368–1644) and founded the Qing dynasty (1644–1912). Again, China was ruled over by a non–Han dynasty from the northeast. The Manchu rulers patronized Tibetan Buddhism to consolidate power over Mongol tribes and other areas under Tibetan influence, sponsoring monasteries, ritual arts, and translation projects.

Despite Stalinist repression in the 1930s and Cultural Revolution purges in China, Buddhism remains a vital religious force in Mongolia and its surrounding areas.

Europe and the Americas

Buddhism’s arrival in Europe and the Americas is a recent chapter in its long history. The first Buddhist community in Europe dates from the 17th century, when Mongols from western Mongolia settled in the Volga basin and practiced a form of Tibetan Buddhism in what is now Kalmykia. Academic interest followed in the 19th century, as European scholars, Theosophists, and intellectuals translated manuscripts and presented Buddhism as an alternative to Western traditions.

Institutional seeds were planted in the early 20th century. Built in 1915 in St. Petersburg, Russia, Gunzechoinei Datsan was one of the first Buddhist temples in Europe. Despite severe state repression and periods of inactivity, this Buryat Buddhist temple is still a place of practice. In 1924, German physician Paul Dahlke established Das Buddhistische Haus in Berlin-Frohnau, today Europe’s oldest Theravada monastery. In London, in 1924, the Buddhist Lodge introduced Buddhist ideas to English circles; its members included philosopher Alan Watts, who later influenced American perceptions of Buddhism. And in 1929, Kalmyk refugees fleeing Bolshevik persecution founded a temple in Belgrade. Although this temple no longer stands, the street where it was built is still called Budvanska (Buddha Street).

Across the Atlantic, immigrant communities established temples in the 19th century. Chinese and Japanese arrivals introduced Mahayana and Zen traditions in Hawaii, California, and beyond as early as the 1850s. Japanese immigrants also built temples in Brazil and Peru, including Jionji, founded in 1908. In North America, Kalmyk refugees founded the first Tibetan Buddhist temple in New Jersey in 1952. And in 1965, the first Theravada monastery in the US was built: the Washington Buddhist Vihara.

The post–World War II and 1960s era brought a surge of interest. Western intellectuals were inspired by Asian scholars such as D. T. Suzuki (1870–1966). At the same time, teachers like Thich Nhat Hanh (1926–2022), Chogyam Trungpa (1939–1987), and the Dalai Lama (b. 1935) created networks, meditation centers, and teaching traditions across Europe and the Americas. Thich Nhat Hanh’s Plum Village center in France remains a well-known hub in the West. By the 1980s, large Theravada communities had formed, such as Wat Buddhanusorn in Fremont, California, and, recently, Wat Nawamintararachutis in Boston, Massachusetts.

As Buddhism became more familiar, words like karma, nirvana, and bodhisattva entered English dictionaries and pop culture—even Taylor Swift sings about karma. Buddhist temples are familiar fixtures across Western cities and towns, and communities have now spread to remote rural areas.

Small immigrant enclaves have grown to become an integral part of Western religious life. Today, Buddhism contributes to the diversity of Europe and the Americas as a global tradition.

New Buddhist Movements

As Buddhism spread globally in the 19th and 20th centuries, new religious movements arose outside traditional monastic and lineage structures. These groups became agents of dissemination, presenting teachings in ways that reached audiences beyond temples. They emphasized accessibility, lay participation, education, and social engagement, carrying Buddhism into spaces where older institutions had little presence.

In mid-20th-century Japan, Soka Gakkai International (SGI) grew from a lay Nichiren tradition into a worldwide movement, spreading chanting practices and peace activism. In 1967, the Triratna Buddhist community (originally known as the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order) was founded in England, introducing Buddhism to new audiences by combining practices from multiple Asian traditions. From the 1970s onward, Tibetan-inspired groups such as Shambhala, Diamond Way, and the New Kadampa Tradition expanded into Europe and the Americas, attracting followers through charismatic teachers and fresh interpretations of doctrine. In post-independence India, the Ambedkarite movement, inspired by B. R. Ambedkar’s 1956 conversion, spread Buddhism among Dalit communities, where it had largely disappeared.

Chinese groups also played a significant role in Buddhism’s modern spread. In 1967, Hsing Yun (1927–2023) founded Fo Guang Shan with its affiliated lay organization, the Buddha’s Light International Association, and in 1976, Sheng-yen (1931–2009) began teaching in the West and, in 1989, founded Dharma Drum Mountain in Taiwan. Both developed large monastic and lay networks and invested heavily in education, publishing, and global outreach.

New movements further expanded dissemination by aligning with popular trends in mindfulness and meditation. Beginning in the late 20th century, these practices were reframed as universal tools and adopted in schools, workplaces, and therapeutic programs. For many groups, they became gateways to introduce their own traditions, while exposing millions to Buddhist-derived practices.

By adapting the tradition to modern needs and audiences, these movements have carried the Buddha’s teachings into neighborhoods, classrooms, and popular culture. The constant rise of new movements has always been part of Buddhism’s history: When the Buddha first began teaching, his community, too, was a new religious movement.

Pilgrimage and the Circulation of Practice

Buddhism has always been a religion on the move. The Buddha himself traveled widely to share his teachings, and after his death, the places tied to his birth, awakening, first teaching, and death became the earliest pilgrimage destinations. The journeys of pilgrims, merchants, and other travelers helped carry Buddhist practices and ideas across the world.

As the tradition spread, new sacred sites emerged, creating a vast network of pilgrimage routes. The Shwedagon Pagoda in Myanmar, Borobudur in Indonesia, Mount Koya in Japan, and Mount Kailash in Tibet are prominent examples. These routes often followed roads used for commerce and official travel, linking monasteries and towns and encouraging exchange among communities. Their influence rose and fell over time, sometimes reshaping local traditions. Today, modern travel brings visitors from around the world to these and many other Buddhist sites.

Global pilgrimage now unites local and international. At Bodhgaya, where the Buddha attained enlightenment, temples representing various Buddhist traditions now stand side by side, and communities from different countries gather annually while maintaining their customs at home. Similar cross-tradition gatherings occur at other Indian sites tied to the Buddha’s life, serving as a shared foundation for the global Buddhist community.

Pilgrimage also broadens understanding of Buddhism’s diversity. Monastic rituals and temple ceremonies attract visitors, while thousands of images are shared daily on social media. Monastics travel internationally, sharing chanting, sand mandalas, and ceremonies, allowing people far from Asia to experience them. Visitors carry home liturgies, images, and stories that shape local practices. Buddhist cultures and rituals now move easily across borders.

Modern transportation has shortened journeys that once took months or years. Sacred sites are also being created outside Asia, opening new pilgrimage routes. Some follow traditional styles, while others are distinctly local—such as the grave of American writer Jack Kerouac, visited by admirers as a Buddhist site. Large temple and stupa projects in Europe and the Americas now anchor annual festivals and retreats that draw participants from many lineages. Pilgrimage continues to adapt, carrying Buddhist traditions into new cultural settings.

The Global Present and the Future of Buddhism

In the 21st century, Buddhism stands at a crossroads shaped by globalization, technology, and shifting cultural values. Teachings and practices have spread widely, reaching millions beyond their traditional homelands and raising new questions about the religion’s future.

In Western cities, Buddhist traditions often stand alongside one another: a Theravada temple, a Tibetan center, and a secular dharma group may all be found on the same street. Buddhist ideas also appear in non-Buddhist spaces, as mindfulness and meditation are now common in workplaces, schools, and therapeutic settings. In Asia, Buddhist communities are responding to rapid modernization and, in some places, a decline in monastic authority. Environmental and economic pressures also affect pilgrimage sites, monasteries, and political stability.

The modern era has also created new opportunities. International travel enables access to teachers, texts, and community, while livestreams, podcasts, and YouTube extend their reach even further. Online archives and e-texts have made scriptures and commentaries widely available, allowing people in rural areas to study Buddhism, learn Pali or Sanskrit, and follow prominent teachers without entering a temple. For some teachers, traveling widely and building a digital presence has replaced the goal of maintaining permanent temples or dharma halls.

Digital adaptation brings both risks and benefits. Virtual communities on Discord, Reddit, and Facebook provide spaces for discussion, study, and support. Online meditation groups are convenient and cost-effective, but the absence of face-to-face interaction can diminish forms of mentorship and communal practice long been considered essential to the Buddhist path. The emergence of AI is poised to accelerate these shifts, though its impact on Buddhist communities remains uncertain.

Looking ahead, the spread of Buddhism will hinge on practical factors already visible today: travel and translation, digital infrastructure, and the strength of local institutions. As teachings move through classrooms, clinics, and online networks—as travelers and pilgrims link communities—practitioners will determine what to preserve and what to adapt. The near future is likely to be shaped by many connected hubs—temples, retreat centers, archives, and digital platforms—through which teachings continue to circulate across borders.

Buddhism for Beginners is a free resource from the Tricycle Foundation, created for those new to Buddhism. Made possible by the generous support of the Tricycle community, this offering presents the vast world of Buddhist thought, practice, and history in an accessible manner—fulfilling our mission to make the Buddha’s teaching widely available. We value your feedback! Share your thoughts with us at feedback@tricycle.org.