Theravada

Theravada Buddhism offers one of the oldest and most enduring paths of Buddhist practice in the world today. Rooted in the Pali canon, it remains the dominant tradition in Sri Lanka and much of mainland Southeast Asia. Theravada emphasizes ethical conduct, disciplined monastic life, and the gradual cultivation of wisdom through meditation. Over time, it has evolved into diverse forms while remaining grounded in ancient principles, offering a wide range of practices for both laypeople and monastics.

Table of contents

- What is Theravada Buddhism?

- History of Theravada

- The Buddha, Buddhas, and Arhats

- The Pali Canon

- Buddhaghosa and the Commentarial Tradition

- Women Renunciants

- Everyday Lay Practice

- Vipassana and Meditation Movements

- Theravada in Southeast Asia Today

- Theravada in the West

- Important Historic and Contemporary Teachers

What is Theravada Buddhism?

Theravada, or the “way of the elders,” is practiced primarily in Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia, all places where it remains the dominant tradition. Theravada traces its roots to the Pali canon, a collection of Buddhist scriptures that emphasize the words of the historical Buddha and the disciplined path he laid out.

Theravada presents itself as the Buddhist tradition closest to the original teachings of the Buddha. Its historical roots likely date back to around the 3rd century BCE, a couple of hundred years after the Buddha, and connect to traditions from the earliest days of Buddhism. Still, the exact origins of Theravada are difficult to determine, as its history rests on much later narratives.

Monastic life is central to Theravada. Monks and nuns observe hundreds of precepts, including refraining from eating after noon and handling money. They are supported by lay followers, who uphold five basic precepts: refraining from killing, stealing, sexual misconduct, lying, and intoxication. While both male and female renunciants exist, fully ordained nuns remain rare, and the issue of female ordination is a subject of debate in many communities.

For fully ordained monks and nuns, who are respectively called bhikkhu (Pali; Skt.: bhiksu) and bhikkhuni (bhiksuni) in Pali, the goal of practice is nibbana (nirvana): the complete release from greed, hatred, and delusion. According to tradition, this realization unfolds over many lifetimes. Those who attain it escape the cycle of birth and death known as samsara.

Theravadins hold that only one fully awakened buddha appears in each era. Siddhattha Gotama (Siddhartha Gautama), who lived about 2,500 years ago, is the buddha of our time. Others who achieve liberation by following his path are known as arahants (arhats), or “worthy ones.” The next buddha, Metteyya (Maitreya), is expected to appear in the distant future.

Although the Buddha has passed into parinibbana (parinirvana)—the final state beyond rebirth—his teachings continue to guide those who follow in his footsteps.

History of Theravada

The historical Buddha died in the 5th century BCE, leaving no appointed successor. In the centuries that followed, the early monastic community, or sangha, held a series of councils to preserve and recite the Buddha’s teachings. Over time, disagreements arose, and the community split into multiple schools, often based on different interpretations of monastic discipline.

One early Indian movement, the Vibhajjavada, distinguished itself from the larger Sthavira tradition, which itself was one of the earliest sects to form after the initial split. The Vibhajjavada emphasized the analytical interpretation of the Buddha’s teachings and was established in Sri Lanka by the 3rd century BCE. The Theravada tradition developed from this Buddhist movement, and later, it, too, split into smaller regional groups. The doctrinal differences among these early schools were relatively minor; they were not defined by sectarian identity in the modern sense but by affiliations with particular monasteries and interpretative approaches. Much about Theravada’s early history, including the name “Theravada” itself, remains uncertain—the term came into general use only in the 19th century, when it became an umbrella label for the southern Buddhist traditions of Sri Lanka and mainland Southeast Asia, as opposed to northern Buddhism of Central and East Asia, or the Mahayana.

By the 5th century CE, Pali had become the primary literary language of many South Asian Buddhist traditions. Local commentaries were translated from Sinhalese into Pali at the Mahavihara monastery in Sri Lanka, forming a textual tradition that would later spread throughout Theravada communities. Though multiple monastic centers once existed in Sri Lanka, including Abhayagiri and Jetavana, the once minor Mahavihara monastic community had become the island’s dominant institution by the 12th century. Its interpretation of doctrine became recognized as orthodox Theravada. Over time, texts were also translated into regional languages, supporting the tradition’s integration across cultures.

Although Buddhism had reached parts of Southeast Asia earlier, the arrival of Sri Lankan monks in the 11th century CE marked a significant turning point in its history. Theravada was soon established as the dominant tradition in Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia, and Thailand. When Sri Lanka’s monastic lineage collapsed after political upheaval during this period, Burmese monks helped reestablish it. Efforts to revive the female bhikkhuni ordination lineage did not begin until much more recently. Ordination lineages have thus played a key role in maintaining the continuity of the Theravada tradition.

Today, Theravada Buddhism continues to thrive in Sri Lanka and mainland Southeast Asia, and has spread globally through migration, reform movements, and the growing popularity of vipassana (insight) meditation.

The Buddha, Buddhas, and Arhats

In the Theravada tradition, there are many buddhas across vast spans of time, but only one arises in each world era. Beings who attain awakening through a buddha’s teachings are known as arahants (Pali; Skt.: arhats), or “worthy ones.”

The Buddhavamsa, a Theravada chronicle of past buddhas, lists twenty-eight buddhas. These buddhas span cosmic time, from Tanhankara Buddha—said to have lived for 100,000 years—through many others who appeared before the present era. Their long histories emphasize the immense effort required to become a buddha.

One of the most revered past buddhas is Dipankara, who predicted that the ascetic Sumedha would eventually become the buddha of our era, Siddhattha Gotama (Pali; Skt.: Siddhartha Gautama). Like others in his lineage, Gotama is said to have cultivated various perfections over countless lifetimes, recounted in the jataka tales. His enlightenment roughly 2,500 years ago marked the culmination of that long path. Becoming a buddha is no small task.

Buddhas must appear in the world so that others can learn the path to liberation. An exception is the paccekabuddha (pratyekabuddha), a solitary awakened one who attains enlightenment independently but does not teach. These figures are portrayed as mysterious and rare, appearing in times when no buddha is present.

Theravada texts also describe progressive stages of awakening for ordinary practitioners. A stream-enterer will be reborn no more than seven more times. A once-returner will reach enlightenment in the next life. A non-returner is reborn in a higher realm and becomes awakened there. An arahant achieves full awakening in this lifetime, with no further rebirth. Many of the Buddha’s closest disciples, such as Ananda, Shariputra, and Uppalavanna, are honored as arahants.

The buddha of our age, Siddhattha Gotama, lived for eighty years. Though fully human, he is remembered as possessing extraordinary qualities. Stories in the Pali texts recount his ability to perform miracles and exhibit superhuman abilities—such as flying, walking on water, or shaking the earth—traits also sometimes attributed to arahants. These accounts highlight the depth of transformation that arises from mental cultivation, as described in early texts.

The Pali Canon

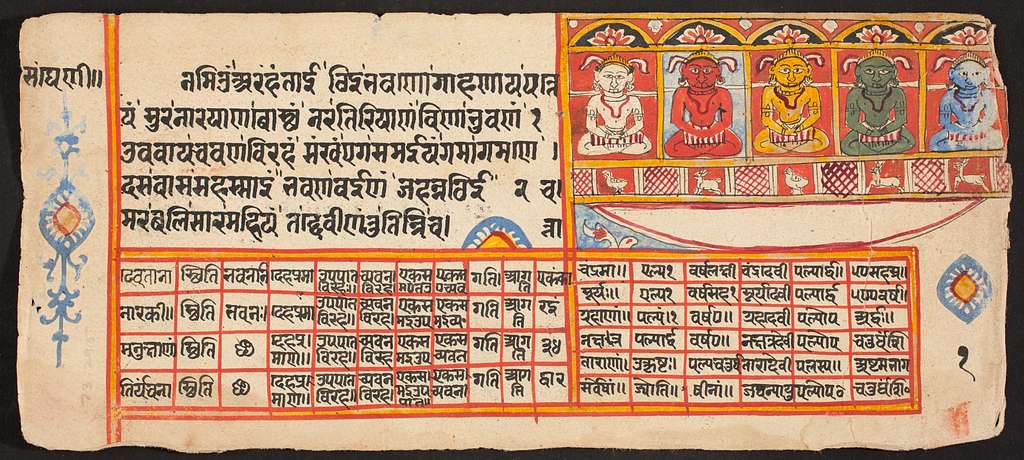

The Pali canon is the foundational collection of scriptures in the Theravada tradition. Pali is an ancient Indian literary language that developed after the Buddha’s lifetime. It is closely related to Sanskrit, and shares many key terms—such as nibbana (Skt.: nirvana) and dhamma (dharma). The Buddha’s teachings were transmitted orally for centuries before being written down in Sanskrit and Pali, a history reflected in the repeated opening line of many suttas: “Thus have I heard.” While some traditions claim the Buddha spoke Pali, it is more accurately described as a standardized language used to preserve early Buddhist teachings.

According to Theravada tradition, the Pali canon was first written down in the 1st century BCE at Aluvihara in Sri Lanka. It covers a range of philosophical, ethical, and contemplative topics, along with examples of the Buddha’s wit. The texts were inscribed on palm-leaf manuscripts, though the earliest surviving fragments are Burmese and date to the 5th or 6th centuries CE, 1,000 years after the Buddha. Older Buddhist texts survive in languages like Gandhari and Chinese, making it difficult to assert that the Pali canon is the oldest. Still, it remains one of the most complete and influential collections of early Buddhist texts.

The canon is called the Tipitaka—“three baskets” (Skt.: Tripitaka)—a term that may refer to the baskets used to store the palm-leaf manuscripts. It includes:

- Vinaya Pitaka: the code of conduct for monastics. These texts include origin stories for many disciplinary rules and often portray the Buddha offering direct guidance to the sangha.

- Sutta Pitaka: a wide-ranging collection of discourses attributed to the Buddha and his close disciples. It includes the jataka tales—stories of the Buddha’s past lives, told to illustrate ethical conduct.

- Abhidhamma Pitaka: a later compilation of scholastic texts that systematically analyze the Buddha’s teachings in technical and philosophical detail.

Over the centuries, the Pali canon has been treated with great respect, chanted during auspicious festivals, and repeatedly copied as a way of generating merit. Beginning in 1860, King Mindon of Myanmar commissioned the carving of the entire canon onto marble tablets. Completed in 1868, the resulting 729 slabs have been referred to as the “world’s largest book.”

Due to the Pali canon’s central importance in the Theravada tradition, a robust commentarial tradition has developed, providing doctrinal interpretation and guidance. Commentaries continue to shape how the canonical sutras, vinaya rules, and philosophical teachings are studied and practiced.

Buddhaghosa and the Commentarial Tradition

Buddhaghosa was an influential Indian scholar-monk of the 5th century CE, whose writings helped shape what is now recognized as classical Theravada Buddhism. His most famous work, the Visuddhimagga (“Path of Purification”), remains one of the most important texts in the tradition outside the Pali canon.

Little reliable information survives about Buddhaghosa’s early life. According to legend, he was born in India—possibly in Bodhgaya—and trained initially as a scholar of the Vedic tradition. One story recounts his conversion to Buddhism after losing a debate with a monk. Some texts suggest that he lived in Kanchipuram, a southern Indian city also associated with Bodhidharma, the legendary founder of Chan Buddhism.

Around 420 CE, Buddhaghosa arrived in Sri Lanka and took residence at the Mahavihara (“great monastery”) in Anuradhapura. The elders there, uncertain of his qualifications, requested that he compose commentaries on the Buddhist suttas. In response, he produced the Visuddhimagga, a comprehensive manual of doctrine, meditation, and ethical training. This monumental work was influenced by the Vimuttimagga, an earlier work attributed to the Sri Lankan monk Upatissa.

Buddhaghosa went on to translate numerous local commentaries—originally preserved in Sinhalese—into Pali, thereby establishing a literary foundation for the Theravada tradition. These works were transmitted to mainland Southeast Asia and became central to the shared textual heritage across Theravada cultures.

Despite being seen as the paradigmatic Theravada scholar, Buddhaghosa never identified with the Theravada school itself. He was affiliated with the older Vibhajjavada tradition and worked within the Mahavihara monastic lineage. Yet many scholars argue that Theravada Buddhism, as it came to be known, was largely shaped by his synthesis of the Sri Lankan Pali textual tradition. One of the restored stupas of the Mahavihara at Anuradhapura, where he is believed to have worked, still stands in northern Sri Lanka.

Although the commentarial tradition predates Buddhaghosa, his systematization marked a turning point. Contemporary commentators, such as Buddhadatta and Dhammapala, expanded on his work, and their commentaries are essential to the study and practice of Theravada today. The commentarial tradition remains vibrant in the West through a new generation of scholar-monks who continue to interpret and transmit Theravada teachings for contemporary audiences.

Women Renunciants

From its beginnings in India, women have been key members of the Buddhist community. The voices of many early nuns are preserved in the Therigatha, a canonical collection of verses and the oldest known anthology of women’s religious poetry. These poems convey the struggles and insights of Buddhist women centuries past, exploring suffering, joy, and the rigors of the monastic path. Although historically subordinated to monks, women today continue to advocate for greater recognition and status in Theravada communities.

According to traditional accounts, five years after his enlightenment, the Buddha reluctantly agreed to ordain women. His stepmother and aunt, Mahaprajapati, became the first bhikkhuni. Texts say the Buddha required her to accept eight special rules (Pali: garudhamma), placing nuns in a subordinate position to monks—stipulations that remain controversial.

The bhikkhuni order spread alongside Buddhism and continues to thrive in Mahayana countries, including China, Taiwan, Korea, Vietnam, and Japan. In Theravada regions, such as Sri Lanka and mainland Southeast Asia, however, the lineage largely disappeared by the 11th century—likely due to war, political upheaval, and the decline of monastic centers—and was never firmly established in countries like Thailand or Myanmar. A key institutional barrier to revival is the vinaya rule requiring a quorum of five bhikkhunis. Since fully ordained nuns do not exist in any of the mainstream Theravada denominations, it is difficult to assemble such a quorum.

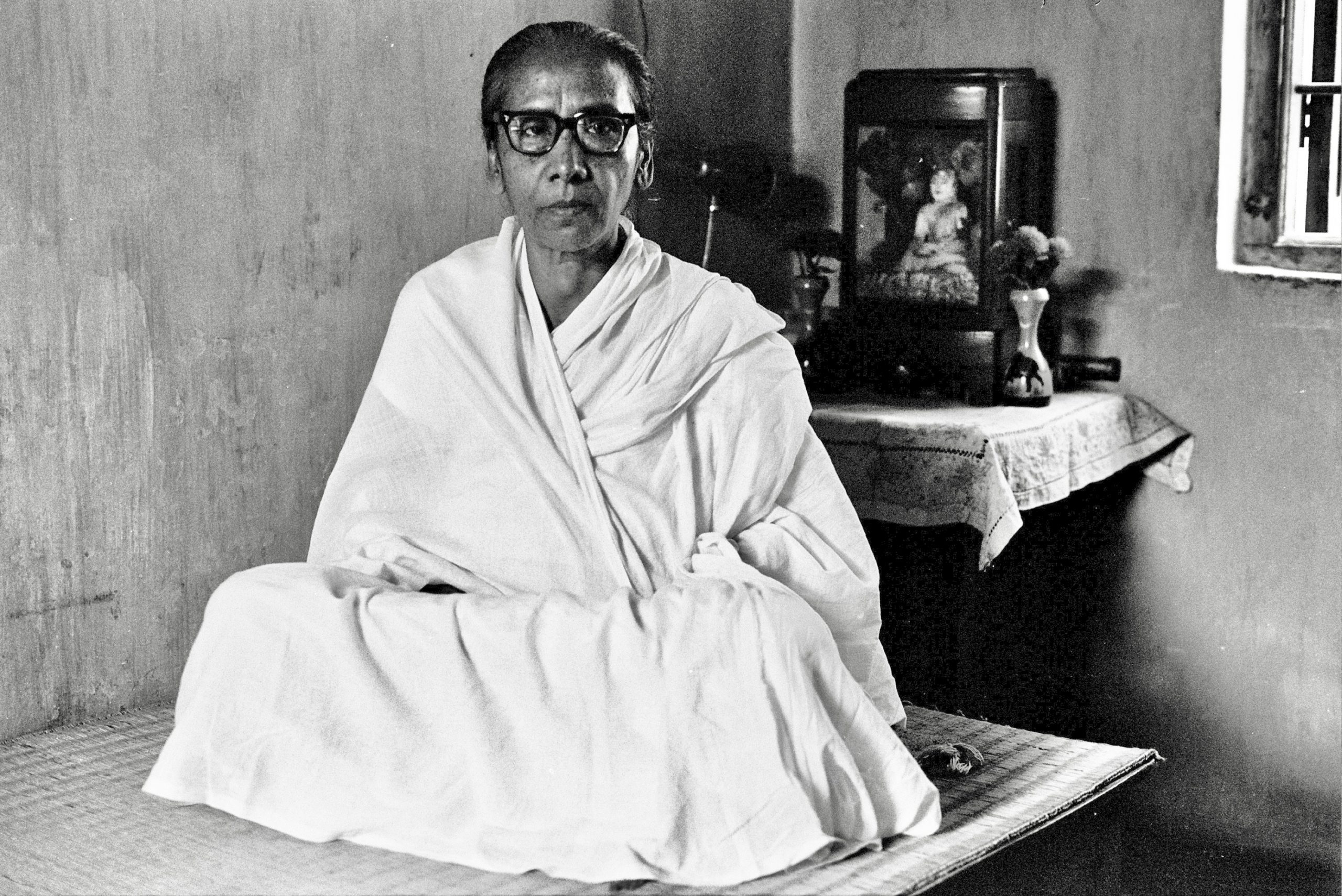

In the 19th and 20th centuries, as Buddhist revival movements emphasized meditation and monastic reform, Theravada women unsatisfied with lay life began forming renunciant communities. These women, often referred to as upasika (laywomen) or anagarika (homeless ones), observe more precepts than laypeople and occupy a status between monastics and laypeople.

Female renunciants go by different names across regions: maechi (“honored mother”) in Thailand, sayalay or thilashin (“possessors of morality”) in Myanmar, donchee (“precept holder”) in Cambodia, and dasasilamata (“mother with ten precepts”) or samaneri (“novice nun”) in Sri Lanka. While not recognized as fully ordained bhikkhunis, they wear robes, shave their heads, live in monastic communities, and often fulfill similar religious roles, relying on lay support. In each case, however, female renunciants have less institutional power and status than fully ordained monks.

Bhikkhuni ordination has reemerged in recent decades, supported by women ordained in Mahayana lineages and organizations such as Sakyadhita. Although not widely accepted by Theravada orthodoxy, these efforts continue to grow, with increasing support from lay communities and pioneering figures such as Bhikkhuni Dhammananda in Thailand. A recent Supreme Court ruling in Sri Lanka has finally granted state recognition to bhikkhunis; so, now it’s up to the Theravada fraternities to follow suit.

Everyday Lay Practice

In Theravada cultures, laypeople tend to focus more on merit-making and ritual observances than on meditation or the pursuit of liberation in this life. Common practices include supporting monastics and monasteries, taking refuge in the three jewels—the Buddha, dhamma, and sangha—and participating in ceremonies and observances. Lay life is often structured around the lunar calendar, with regular uposatha (ritual observance) days and festivals such as Vesak, which marks the Buddha’s birth, enlightenment, and passing.

Supporting the monastic community is a central aspect of lay practice. By donating the four requisites for renunciant life—food, robes, shelter, and medicine—laypeople generate merit for future lives while enabling monastics to pursue their training. Lay Buddhists also assist with temple upkeep, communal meals, and religious events. Most lay followers observe the five precepts: refraining from killing, stealing, sexual misconduct, lying, and intoxication. On uposatha, additional precepts may be taken.

At temples, laypeople light incense, offer flowers, chant, and request blessings. Monastics provide spiritual guidance and perform rituals on behalf of families or local communities. In rural areas, monasteries also serve broader social functions, including education, health care, and cultural events. Many homes also contain altars with images of Buddha, where offerings are made daily.

Merit-making is closely tied to beliefs in karma and rebirth. By performing good deeds, lay Buddhists hope to improve their future circumstances—whether through better health, prosperity, or a favorable rebirth. Alongside these karmic aims, protective rites are also common. Chanting Paritta suttas, tying sacred threads, receiving tattoos, and using amulets—sometimes containing relics like the ashes of revered teachers—are standard practices for warding off misfortune and illness.

Monks have long served both religious and practical roles, offering blessings, medical care, and apotropaic rites for laypeople. These include protective chants, divination, and the preparation of charms. Rather than being seen as superstitious, such rituals are typically understood as compassionate methods for alleviating everyday suffering.

Although meditation has become more accessible in recent decades, regular meditative practice remains relatively rare among laypeople. Still, lay practitioners play an increasingly important role in popularizing and spreading meditation practices rooted in Theravada teachings, both locally and globally.

The relationship between sangha and laity remains one of mutual dependence: Monastics rely on lay support for their material needs, while laypeople rely on monastics for teachings, blessings, and guidance. This interdependence is a defining feature of Theravada Buddhist life.

Vipassana and Meditation Movements

For much of Buddhist history, meditation was primarily reserved for monastic communities—and even among monastics, accomplished practitioners were rare. A layperson with a sustained meditation practice was unusual, though some suttas do mention such individuals. That changed over the past 150 years, when a wave of modern reform movements across Southeast Asia and Sri Lanka revitalized Buddhist practice and made meditation more widely accessible.

This revival emerged partly in response to colonialism and Christian missionary competition, which prompted Buddhist leaders to emphasize scripture, meditation, and education. Reformers, influenced by Western ideas and philosophical inquiry, sought to articulate Buddhism as a rational and experiential path aligned with science, rather than merely relying on ritual or devotion.

In Myanmar, a modern vipassana meditation movement developed that emphasized mindfulness (Pali: sati; Skt.: smrti) and insight (vipassana; vipasyana) grounded in early texts like the Satipatthana Sutta. Lay retreat models were introduced, allowing householders to participate in meditation practice. This movement marked a significant shift from centuries of monastic exclusivity.

In Sri Lanka, reformers likewise emphasized meditation and scriptural literacy, leading to the establishment of nonmonastic meditation centers in urban areas. In Thailand, a modern form of the Thai forest tradition gained new popularity, particularly among Westerners, emphasizing the strict observance of the vinaya and meditative discipline. These efforts attracted both monastics and laypeople seeking direct experience of the Buddha’s path.

The Indian lay teacher S. N. Goenka, who trained in Myanmar, helped globalize insight meditation by teaching a nonsectarian approach focused on direct experience. His retreats reached students worldwide and helped pave the way for secular mindfulness movements in the West.

Today, vipassana meditation is practiced by a broad range of people—monastics and laypeople, from Asia and the West—through city centers, forest monasteries, global retreat networks, and digital platforms. While daily meditation remains uncommon among most lay Theravadins, its influence continues to grow.

Though shaped by different teachers and regional histories, these meditation movements are now central to modern Theravada identity. And they all share a common goal: making the liberating insights of the Buddha accessible to a broader range of practitioners in a changing, global world.

Theravada in Southeast Asia Today

Although historically rooted in Sri Lanka, Theravada Buddhism became a vital religious and cultural force in Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos. While these regions share canonical texts and monastic structures, each country’s unique history and culture led to its own distinctive Buddhist tradition.

Across the Theravada world, monasteries remain central institutions, both religiously and economically. They serve as sites of ritual, education, and community life. In rural areas, they may also function as schools or clinics. In urban centers, some monasteries have become hubs for meditation and Buddhist reform. Monastics rely on laypeople for material support, forming a mutually beneficial economy of merit.

The Covid-19 pandemic posed serious challenges for monastic communities, which depend on close interaction with the laity. In Thailand, monks reversed traditional roles by offering aid to laypeople facing illness and economic hardship. Meanwhile, nonmonastic meditation centers and lay teachers—especially in cities—continue to expand in reach and influence.

Women face both growing opportunities and enduring constraints across the region. Laywomen play central roles in temple support and household devotion, participating in rituals, almsgiving, and festivals. Yet fully ordained bhikkhunis remain rare. In Sri Lanka, a revived bhikkhuni lineage has received modest lay support but faces strong opposition from the monastic hierarchy. In Thailand, Myanmar, and Cambodia, only informal ordination is available. Although far more visible than nuns, laywomen may gain new visibility as female ordination efforts progress slowly.

Popular lay practices include almsgiving, lighting incense, and participating in festivals. In Thailand and Laos, protective amulets are common. Throughout Southeast Asia, local spirit rituals often accompany Buddhist ceremonies. Devotion to relics, sacred images, and texts remains widespread. Despite social and political changes, rituals involving astrology, healing, and ancestor veneration are viewed as part of, rather than in conflict with, Buddhist teachings.

Reform movements shaped by Buddhist modernism emphasize rationality, meditation, and social engagement. In Sri Lanka, groups like the Sarvodaya Shramadana Movement promote socially engaged Buddhism. Vipassana movements in Myanmar have influenced both local and global practice. These reforms tend to downplay ritual and supernatural beliefs, but their appeal is often limited to urban elites.

Theravada in Southeast Asia is marked by contrasts: between tradition and reform, rural and urban life, and monastic and lay agency. As monasteries adapt and lay roles evolve, the tradition continues to respond to the changing societies it serves.

Theravada in the West

Theravada Buddhism has established a modest but influential presence in the West, particularly in North America and Europe. It arrived in earnest in the mid-20th century, through a combination of academic interest, spiritual searching, and the efforts of Asian teachers and Western converts. Today, its most visible expression is the vipassana (insight) meditation movement, which has helped shape the language of secular mindfulness, Buddhist practice, and psychological well-being.

Initial Western interest emerged in the late 19th century, when the Pali Text Society began publishing English translations of Buddhist scriptures, including the Satipatthana Sutta, a foundational text on mindfulness. Theosophists and early scholars were drawn to the Theravada tradition, especially in Sri Lanka. But it was not until the 1960s and ’70s that Western travelers began encountering living Theravada practice in Thailand, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and India. Many studied vipassana under renowned teachers like Mahasi Sayadaw (1904–1982), Sayagyi U Ba Khin (1899–1971), Anagarika Munindra (1915–2003), and Ajaan Chah (1918–1992), then returned home to teach.

The insight movement, rooted in Burmese vipassana methods, took shape in the West with a lay-oriented, nonsectarian ethos. Institutions like the Insight Meditation Society (IMS) in Massachusetts and Spirit Rock in California have become influential models for intensive retreats that emphasize meditation, silence, and dharma talks. Teachers such as Joseph Goldstein, Jack Kornfield, and Sharon Salzberg helped popularize mindfulness, loving-kindness, and compassion.

Alongside this lay model, the Thai forest tradition also gained a Western following. Emphasizing renunciation, vinaya discipline, and meditative rigor, it spread through teachers such as Ajaan Sumedho and monasteries like Abhayagiri and Metta Forest Monastery, in California, and Amaravati, in the UK. These communities preserve a more traditional, monastic form of Theravada; in some cases, they have also sponsored the ordination of nuns.

In both expressions—lay-centered and monastic—Western Theravada tends to emphasize meditation over ritual, personal insight over religious hierarchy, and psychological well-being over cosmological belief. Teachings on karma and rebirth are often reinterpreted or downplayed.

Immigrant communities from Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia maintain more traditional Theravada forms in the West, offering temple life and devotional practices for their diasporas. Some also welcome non-immigrant practitioners.

Overall, Theravada in the West reflects a blend of ancient tradition and modern sensibilities. Whether in monasteries or meditation halls, its teachings continue to resonate with those seeking clarity, compassion, and contemplative insight.

Important Historic and Contemporary Teachers

A wide range of teachers has shaped Theravada Buddhism—from early scholar-monks to modern reformers and global meditation masters—whose work continues to influence how the tradition is studied and practiced today.

In the classical period, the Indian monk Buddhaghosa systematized the teachings preserved in Sri Lanka’s Mahavihara tradition. His 5th-century treatise, the Visuddhimagga (Path of Purification), remains central to the study and practice of Theravada Buddhism. Later, monk-scholars, such as Dhammapala and Buddhadatta, expanded the commentarial tradition with new works on neglected parts of the canon and further reflections on Buddhaghosa’s contributions.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, reformist teachers played a crucial role in revitalizing meditation, ethics, and Buddhist education across Southeast Asia. In Myanmar, Ledi Sayadaw (1846–1923) advocated for lay meditation and scriptural literacy, laying the foundation for the global insight (vipassana) movement. His student, Mahasi Sayadaw (1904–1982), helped spread vipassana internationally by training both Burmese and Western students. Anagarika Dharmapala (1864–1933) of Sri Lanka introduced Theravada to Western audiences and played a pivotal role in revitalizing Bodhgaya as a modern pilgrimage site.

In Thailand, Ajaan Mun Bhuridatta (1870–1949) and his disciple Ajaan Chah (1918–1992) revitalized forest monasticism, combining meditative rigor with close attention to the vinaya. Buddhadasa Bhikkhu (1906–1993) reinterpreted traditional doctrines in modern terms, emphasizing the unity of religious insight. His monastery, Suan Mokkh, became a training ground for international students.

Among Thailand’s respected lay teachers, Upasika Kee Nanayon (1901–1978) offered direct, uncompromising guidance grounded in personal experience. In India, Dipa Ma (1911–1989), one of Mahasi Sayadaw’s most influential lay disciples, demonstrated that deep meditative realization was possible even amid everyday life, and inspired many of the teachers who carried insight practice to the West.

Western-born monastics have also shaped modern Theravada. Nyanatiloka Mahathera (1878–1957) translated key texts and helped establish a Western monastic lineage. His student, Nyanaponika Thera (1901–1994), cofounded the Buddhist Publication Society and introduced mindfulness to a global audience. Ayya Khema (1923–1997) helped expand opportunities for female renunciants and founded meditation centers worldwide. Today, Western monks such as Bhikkhu Bodhi, Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu, and Bhikkhu Anālayo continue the tradition of translation, commentary, and teaching.

These teachers represent the evolving face of Theravada. Their teachings guide practitioners across cultures and generations, sustaining the tradition while responding to new contexts and challenges.

Buddhism for Beginners is a free resource from the Tricycle Foundation, created for those new to Buddhism. Made possible by the generous support of the Tricycle community, this offering presents the vast world of Buddhist thought, practice, and history in an accessible manner—fulfilling our mission to make the Buddha’s teaching widely available. We value your feedback! Share your thoughts with us at feedback@tricycle.org.